medium | Earlier this summer, I presented the American Nations:

the eleven regional cultures that comprise the United States and North

America. Their existence explains much about our history, our constitutional arrangements,

and, indeed, our political fissures — past and present. If you have any

ancestors who were living in North America prior to the Civil War, the

existence of these rival nations is likely reflected in parts of your

family tree and, according to a recent study published in Nature Communications, may very well have left a mark on your DNA.

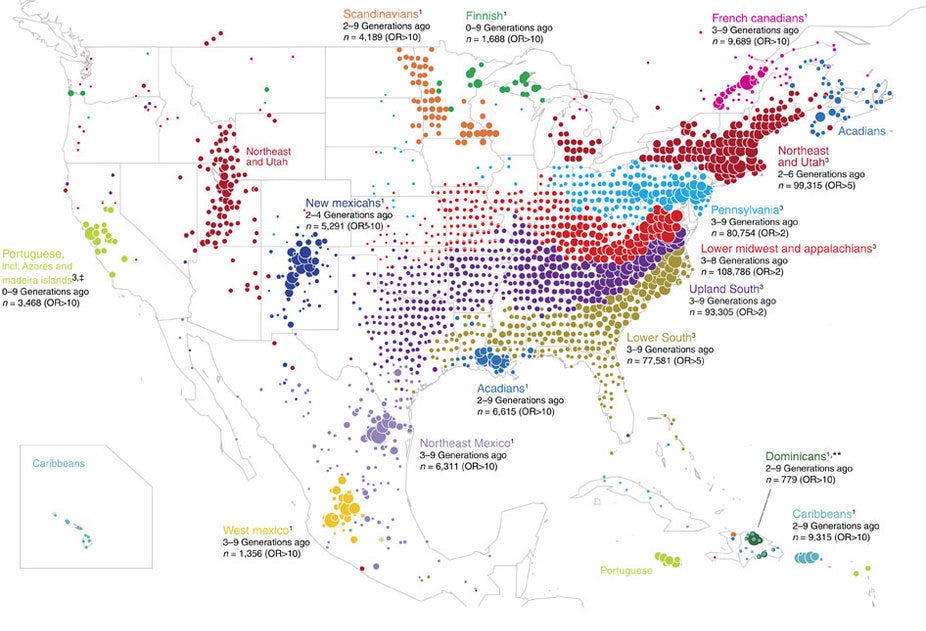

I couldn’t miss this study, because shortly after it came out, readers of my 2011 book, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America,

were stuffing my inbox and flooding my social media feeds with it. A

glance at the thumbnail illustration that accompanied the study made it

clear why: Unbeknownst to the scientists who’d written the paper, the

map depicting the key results of their research on the patterns of

genetic variation in North America over time and space mirrored the

American Nations map to an uncanny degree.

Here they are for comparison:

|

Clustering of 770,000 genomes reveals post-colonial population structure of North america. Nature Communications 8 (2017)

This

is remarkable because the American Nations paradigm is resolutely not

about genetics or genealogy. Rather, it’s built on the late cultural

geographer Wilbur ZeFrolinsky’s Doctrine of First Effective Settlement,

which argues that when a “new” society is settled, the cultural

characteristics of the initial settlement group will have a lasting and

outsized effect on the future trajectory of that society — even if their

numbers were very small and those of later immigrants of different

origins were very large. These lasting characteristics, which inform the

dominant culture of entire regions of North America, are passed down

culturally, not genetically, which explains why the Dutch-settled area

around New York City still has obvious and distinct characteristics

inherited from Golden Age Amsterdam, even though the portion of people

there reporting Dutch ancestry to census takers is a vanishingly small

0.2 percent. Culture is learned, not inherited.

And yet the Nature

study — powered by the enormous cross-referenced genomics and genealogy

databases of Ancestry.com — reveals that the regional cultures have

left a significant genetic imprint as well. That’s because members of a

regional culture tended to mate with one another, rather than with

people from rival areas, even when those rivals lived nearby, in the

very same colony or state.

“Who

we are today — the genetics of Americans all over the place — is the

result of all kinds of cycles of reproductive isolation and the release

of that isolation,” says Catherine A. Ball, a geneticist and the chief

scientific officer at Ancestry who oversees the company’s DNA work. “Who

your mates would be was linked to geography, politics, religion, war,

and all of that is showing today in people walking on the streets and

who they are related to.”

Ball wasn’t familiar with American Nations

before I spoke with her, but the results show that the boundaries of

the regional cultures were very real when it came to human reproduction,

creating reproductive clusters centuries ago that geneticists have been

able to recreate through the examination of nearly a million living

Americans’ DNA.

0 comments:

Post a Comment