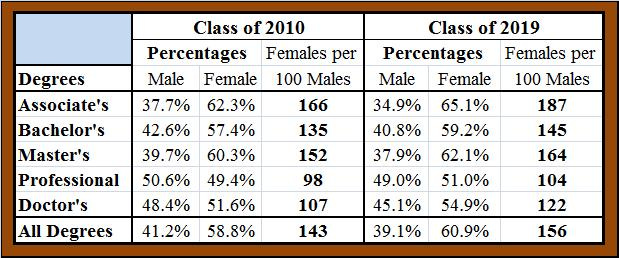

Time | While people of color, individually and as groups, have been helped

by affirmative action in the subsequent years, data and studies suggest

women — white women in particular — have benefited disproportionately. According to one study,

in 1995, 6 million women, the majority of whom were white, had jobs

they wouldn’t have otherwise held but for affirmative action.

Another study

shows that women made greater gains in employment at companies that do

business with the federal government, which are therefore subject to

federal affirmative-action requirements, than in other companies — with

female employment rising 15.2% at federal contractors but only 2.2%

elsewhere. And the women working for federal-contractor companies also

held higher positions and were paid better.

Even in the private sector, the advancements of white women eclipse those of people of color. After IBM established

its own affirmative-action program, the numbers of women in management

positions more than tripled in less than 10 years. Data from subsequent

years show that the number of executives of color at IBM also grew, but not nearly at the same rate.

wikipedia | As chairman of the United States House Committee on Rules starting in 1954,[5]

Smith controlled the flow of legislation in the House. An opponent of

racial integration, Smith used his power as chairman of the Rules

Committee to keep much civil rights legislation from coming to a vote on

the House floor.

He was a signatory to the 1956 Southern Manifesto that opposed the desegregation of public schools ordered by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education

(1954). A friend described him as someone who "had a real feeling of

kindness toward the black people he knew, but he did not respect the

race."[6]

When the Civil Rights Act of 1957

came before Smith's committee, Smith said, "The Southern people have

never accepted the colored race as a race of people who had equal

intelligence and education and social attainments as the whole people of

the South."[7] Others noted him as an apologist for slavery who used the Ancient Greeks and Romans in its defense.[6]

Speaker Sam Rayburn tried to reduce his power in 1961, with only limited success.

Smith delayed passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

One of Rayburn's reforms was the "Twenty-One Day Rule" that required a

bill to be sent to the floor within 21 days. Under pressure, Smith

released the bill.

Two days before the vote, Smith offered an amendment to insert "sex" after the word "religion" as a protected class of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Congressional Record

shows Smith made serious arguments, voicing concerns that white women

would suffer greater discrimination without a protection for gender.[8] Reformers, who knew Smith was hostile to civil rights for blacks, assumed that he was doing so to defeat the whole bill.[9][10]

In 1968, Leo Kanowitz wrote that, within the context of the anti-civil

rights coalition making "every effort to block" the passage of Title

VII, "it is abundantly clear that a principal motive in introducing

["sex"] was to prevent passage of the basic legislation being considered

by Congress, rather than solicitude for women's employment rights."[11] Kanowitz notes that Representative Edith Green,

who was one of the few female legislators in the House at that time,

held that view that legislation against sex discrimination in employment

"would not have received one hundred votes," indicating that it would

have been defeated handedly.

In 1964, the burning national issue was civil rights for blacks.

Activists argued that it was "the Negro's hour" and that adding women's

rights to the bill could hurt its chance of being passed. However,

opponents voted for the Smith amendment. The National Woman's Party (NWP) had used Smith to include sex as a protected category and so achieved their main goal.[12]

The prohibition of sex discrimination was added on the floor by

Smith. While Smith strongly opposed civil rights laws for blacks, he

supported such laws for women. Smith's amendment passed by a vote of 168

to 133.[10][13][14]

Smith expected that Republicans,

who had included equal rights for women in their party's platform since

1940, would probably vote for the amendment. Some historians speculate

that Smith, in addition to helping women, was trying to embarrass Northern Democrats, who opposed civil rights for women since labor unions opposed the clause.[8]