frontiersin | Individuals with a predisposition to mental disorder may

utilize different strategies, or they may use familiar strategies in

unusual ways, to solve creative tasks. For over a century, knowledge of

psychopathological states in the brain has illuminated our knowledge of

normal brain states, and that should also be the case with the study of

the creative brain. Neuroscience can approach this study in two ways.

First, it can identify genetic variations that may underlie both

creativity and psychopathology. This molecular biology approach is

already underway, with several studies indicating polymorphisms of the

DRD2 and DRD4 genes (Reuter et al., 2006; Mayseless et al., 2013), the 5HT2a gene (Ott et al., 2005) and the NRG1 gene (Kéri, 2009) that have been associated with both creativity and certain forms of psychopathology.

Second, brain imaging work can be applied to the study

of the cognitive mechanisms that may be commonly shared between

creativity and psychopathology. For example, psychologists have long

suggested that both schizotypal and highly creative individuals tend to

utilize states of cognitive disinhibition to access associations that

are ordinarily hidden from conscious awareness (e.g., Kris, 1952; Koestler, 1964; Eysenck, 1995).

Research is revealing that indeed both highly creative subjects and

subjects who are high in schizotypy demonstrate more disinhibition

during creative tasks than less creative or less schizotypal subjects

(see Martindale, 1999; Carson et al., 2003; Abraham and Windmann, 2008; Dorfman et al., 2008). However, the neural substrates of cognitive disinhibition, as applied to creativity, need to be further studied.

My colleagues and I have found that cognitive

disinhibition (in the form of reduced latent inhibition) combined with

very high IQ levels predicts extraordinary creative achievement (Carson et al., 2003). These results have since been replicated (Kéri, 2011).

We hypothesized that cognitive disinhibition allows a broadening of

stimuli available to consciousness while high IQ affords the cognitive

resources to process and manipulate that increased stimuli to form novel

and creative ideas without the individual becoming overwhelmed and

confused. What we did not test is whether the high creative achievers in

our studies exhibited phasic changes in latent inhibition, or whether

their reduced inhibition was more trait-like, as is seen in persons at

risk for psychosis. Because latent inhibition tasks are compatible with

neuroimaging, the study of controlled cognitive disinhibition is one

area of potential study for the neuroscience of creativity.

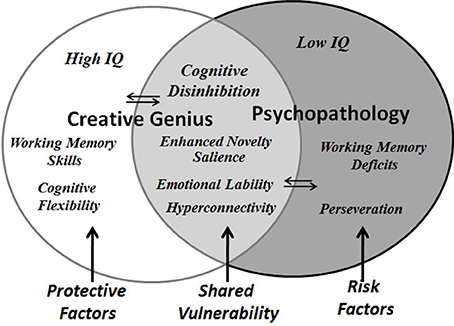

Additional areas of study are suggested by the shared vulnerability model of creativity and psychopathology (Carson, 2011, 2013).

The shared vulnerability model suggests that creativity and

psychopathology may share genetically-influenced factors that are

expressed as either pathology or creativity depending upon the presence

or absence of other moderating factors (see Figure 1).

The shared vulnerability components that have been identified, in

addition to cognitive disinhibition, include novelty salience, neural

hyperconnectivity, and emotional lability.

12 comments:

.....If this post was put up to elicit some wisecrack from BD, about Charles Barkley, it failed....

Lamborghini Mercy Big Dawn she's so thirsty..., http://youtu.be/7Dqgr0wNyPo

....60 Minutes had a great segment tonight on Genetics.....

BD will see your IQ75 Bling-centric Dysfunction and raise you some IQ160 awesome new technology--->http://www.the-peak.ca/2014/10/genetic-engineering-takes-steps-towards-building-superhumans/

po thang...,

Good luck with that awesome new technology dood. Do you expect it to bear fruit before the anti-matter reactors and matter teleportation systems, or will it be out there around the time of the faster-than-light warp drives?

I'll try to recircle to the main question I had intended to raise

1) http://www.genome.gov/27559120

Summary version: "The genomic analysis revealed that the current version of the virus in West Africa most likely spread from Middle Africa within the past 10 years. They also found that the viruses causing this outbreak and the two previous ones diverged from a common ancestor around 2004. This means that these outbreaks arose from different "jumps" from the animal reservoir to the human population."

Detailed version: "We combined the 78 Sierra Leonean sequences with three published Guinean samples (3) [correcting 21 likely sequencing errors in the latter (6)] to obtain a data set of 81 sequences. They reveal 341 fixed substitutions (35 nonsynonymous, 173 synonymous, and 133 noncoding) between the 2014 EBOV and all previously published EBOV sequences, with an additional 55 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; 15 nonsynonymous, 25 synonymous, and 15 noncoding), fixed within individual patients, within the West African outbreak. Notably, the Sierra Leonean genomes differ from PCR probes for four separate assays used for EBOV and pan-filovirus diagnostics (table S3). Deep-sequence coverage allowed identification of 263 iSNVs (73 nonsynonymous, 108 synonymous, 70 noncoding, and 12 frameshift) in the Sierra Leone patients (6). For all patients with multiple time points, consensus sequences were identical and iSNV frequencies remained stable (fig. S4). One notable intrahost variation is the RNA editing site of the glycoprotein (GP) gene (fig. S5A) (10–12), which we characterized in patients (6)."

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1404505#t=article

Phylogenetic analysis of the full-length sequences established a separate clade for the Guinean EBOV strain in a sister relationship with other known EBOV strains. This suggests that the EBOV strain from Guinea has evolved in parallel with the strains from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Gabon from a recent ancestor and has not been introduced from the latter countries into Guinea

Q: If the virus were recently engineered, why do researchers generally believe it looks like other strands which have been making the rounds for the past decade?

BTW - I didn't mean to be inhospitable, welcome to the spot. Let me ruminate a bit and and get back at you.

lol, I knew I smelled herring liberally sprinkled with straw..., Boyle did not assert that the virus was GMO. (I certainly made no such assertion) - rather - Boyle contended that an accident in one of the research labs was the likely culprit. For my own part, I derided the moral integrity and ethical praxis of a country which maintains 120 bioweapons research labs from which such an horrific accident most likely emanated.

Which begs the kwestin Dr. Drew "with whom are you debating?"

...Woo-Hoo...!! even public schools are now on the DNA bandwagon - behavior tendencies are Genetic ---> http://www.mlive.com/news/flint/index.ssf/2014/10/flint_school_district_students.html

No problem, no inhospitably detected. Sorry if passive aggressiveness was present in the original line of questioning.

An interesting nugget to me was that Boyle responded to some of this today:

http://www.washingtonsblog.com/2014/10/bioweapons-expert-reaffirms-belief-ebola-escaped-biowarfare-lab.html

I found Boyle's claims about "the US military set up their first ebola testing center in Liberia in an abandoned lab filled with bats" specifically interesting.

Sorry, master debater here.

In terms of accidents, I agree the probability of an accident at these labs is unfortunately high, as has been documented in numerous incidents, biological and nuclear, across several countries.

On an interesting note, the U.S. has studied bats as a potential weapon historically:

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0292718721/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0292718721&linkCode=as2&tag=economiccom0e-20&linkId=4DEAM3X6CFQM3AAJ

Anyways thanks for the discussion, even if I misguided myself..

"Boyle contended that an accident in one of the research labs was the likely culprit." Just like its filovirus cousin Marburg, which "jumped out" of a green monkey in German lab, and started killing people in Afrika. Maybe George W. Bush can explain where those natural reservoirs hang out between outbreaks. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f_tFKa2_YBQ

Post a Comment