salon | The big news after President Obama’s State of the Union address in

January was that he didn’t really talk about the issues of inequality

that everyone expected him to talk about. Instead, he shifted the

“conversation,” as we call it, toward the subject of opportunity. He

shied away from the extremely disturbing fact that when you work these

days only your boss prospers, and brought us back to the infinitely less

disturbing fact that sometimes poor people do get ahead despite it all.

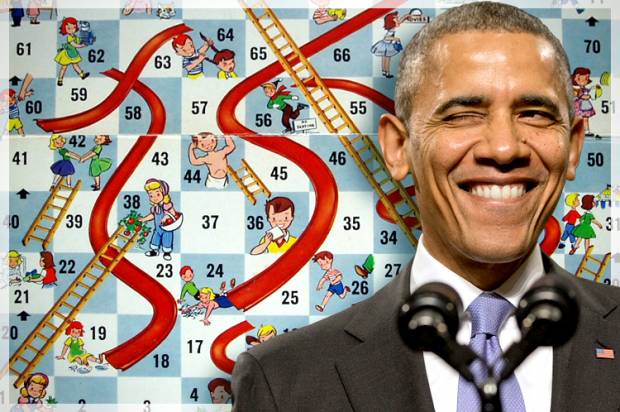

In a clever oratorical maneuver, Obama illustrated this comforting idea

by referencing the success stories of both himself—“the son of a single

mom”—and his arch-foe, Republican House Speaker John Boehner—“the son

of a barkeep.” He spoke of building “new ladders of opportunity into the

middle class,” a phrase that has become a trademark for his administration.

The

problem, as Obama summed it up, is that Americans have ceased to

believe they can rise from the ranks. “Opportunity is who we are,” he

said. “And the defining project of our generation must be to restore

that promise.”

The switcheroo was subtle, but if you’ve been

paying attention you couldn’t miss it: These were almost precisely the

words Obama had used the month before (“The defining challenge of our

time”) to describe inequality itself.

Well, the Democratic apparat

heard it, and as one body did they sway and swoon. This was a move of

statesmanlike genius, they said. “Opportunity” and social mobility are

what Americans have always liked to hear about, they declared;

“inequality” sounds like a demand for entitlements—or something much

worse. “What you want to do is focus on the aspirational side of this,”

said Paul Begala in a typical remark, “lifting people up, not on just

complaining about a lack of fairness or inequality.”

If you’re in

the right mood, you might well agree with him. In the distant past,

“opportunity” used to be something of a liberal buzzword, a way of

selling welfare-state inventions of every description. The reason was

simple: true equality of opportunity is not possible without achieving,

well, greater equality, period. If we’re really serious about

opportunity—if we’re going to ensure that every poor kid has a chance in

life that is the equal of every rich kid—it’s going to require a

gigantic investment in public schools, in housing, in food stamps, in

infrastructure, in public projects of every description. It will

necessarily mean taking on the broader problem of the One Percent along

the way.

But

that was what the word meant long ago. It’s different today. When

people talk about opportunity nowadays, they’re often not trying to

refine the debate over inequality, they’re trying to negate it. The

social function of mobility-talk is usually to excuse

inequality, not to change it; to persuade us that the system we have now

is fair and even natural—or that it can be made so with a few more

charter schools or student loans or something. Because everyone has a

chance at making it into the One Percent, this version of “opportunity”

tells us, there’s nothing wrong with letting the One Percent hog every

dish at the banquet. Fist tap Vic.

0 comments:

Post a Comment