newyorker | The closest Hirschman ever came to explaining his motives was in his

most famous work, “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty,” and even then it was only

by implication. Hirschman was interested in contrasting the two

strategies that people have for dealing with badly performing

organizations and institutions. “Exit” is voting with your feet,

expressing your displeasure by taking your business elsewhere. “Voice”

is staying put and speaking up, choosing to fight for reform from

within. There is no denying where his heart lay.

Early in the

book, Hirschman quoted the conservative economist Milton Friedman, who

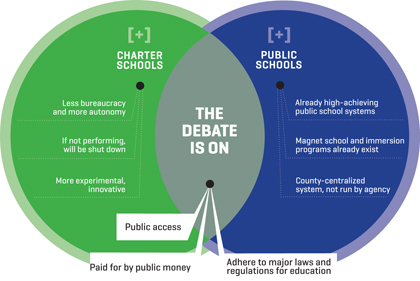

argued that school vouchers should replace the current public-school

system. “Parents could express their views about schools directly, by

withdrawing their children from one school and sending them to another,

to a much greater extent than is now possible,” Friedman wrote. “In

general they can now take this step only by changing their place of

residence. For the rest, they can express their views only through

cumbrous political channels.”

This was, Hirschman wrote, a “near perfect example of the economist’s bias in favor of exit and against voice”:

In the first place, Friedman considers withdrawal or exit as the “direct” way of expressing one’s unfavorable views of an organization. A person less well trained in economics might naively suggest that the direct way of expressing views is to express them! Secondly, the decision to voice one’s views and efforts to make them prevail are contemptuously referred to by Friedman as a resort to “cumbrous political channels.” But what else is the political, and indeed the democratic, process than the digging, the use, and hopefully the slow improvement of these very channels?

Hirschman

pointed out the ways in which “exit” failed to send a useful message to

underperformers. Weren’t there cases where monopolists were relieved

when their critics left? “Those who hold power in the lazy monopoly may

actually have an interest in creating some limited opportunities

for exit on the part of those whose voice might be uncomfortable,” he

wrote. The worst thing that ever happened to incompetent public-school

districts was the growth of private schools: they siphoned off the kind

of parents who would otherwise have agitated more strongly for reform.

Beneath Hirschman’s elegant sentences, you can hear a deeper argument. Exit is passive.

It is silent protest. And silent protest, for him, is too easy.

“Proving Hamlet wrong” was about the importance of acting in the face of

doubt—but also of acting in the face of fear. Voice was courage.

8 comments:

"The worst thing that ever happened to incompetent public-school districts was the growth of private schools: "

Private schools have always existed. But it was Brown vs. Board - destroyed the learning environment that necessitated migration to and growth of private schools....

Brown vs. Board didn't destroy the learning environment and there has never been any need for migration outside the minds of white racists and the snake oil hucksters who pandered to the neurotic tendencies of the same, like for example old Jesse Clyde http://subrealism.blogspot.com/2013/06/american-political-science-architect-of.html

Have tablet computers made the public/charter debate irrelevant?

Is the fact that educators have not been advocating a National Recommended Reading List for decades evidence that education has never been the primary objective?

Now the issue is what to load on the tablets just like the issue would have been what books to put in the list? If the list issue had ever come up, that is.

This would have been so much fun in high school:

The Tyranny of Words (1938) by Stuart Chase

http://www.anxietyculture.com/tyranny.htm

http://archive.org/details/tyrannyofwords00chas

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9H1StY1nU8

Flipped instruction has made the public/charter debate irrelevant. http://subrealism.blogspot.com/2013/06/21st-century-instruction-making.html

In fact, it has made the entire 19th century pedagogical and learning model irrelevant but the status quo institutions cannot do anything but fight and resist this change tooth and nail. That spells opportunity to smart, enterprising and savvy interlopers with no vested interest in the status quo educational delivery model.

You're living in a dreamworld. The black people didn't take away our educational system, it just never was very good. Take some freaking responsibility.

lol, as an "educational system" it's miserable, as a "sorting system" it's superb. If your goals are containment, compliance, and conformity - accept no substitutes. If your goal is to actually temper and free young minds, not so much.

In Big Don's political ecology, contact with blacks in the sorting system probably was/is tantamount to "destruction of the learning environment".

Yeah, it's a circular definition. My own prejudice is that the worst schools -- by far -- that I've attended were 99% white. So I been to the golden age already, and it sucked.

BD got out of college in the mid-60's, so his assertions about the effect of Brown vs. Board on the "learning environment" reflect this era http://subrealism.blogspot.com/2013/02/not-so-long-ago.html and one can only imagine how oppressively integrated that must have been in Washington state.

Post a Comment