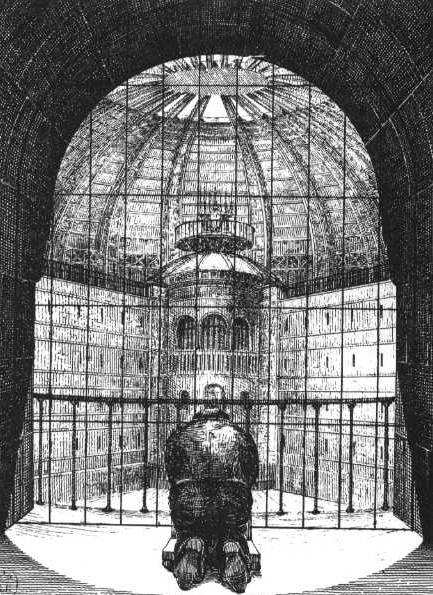

nakedcapitalism | A prisoner kneels before the watchtower in a drawing of Jeremy Bentham’s ‘Panopticon’. The Panopticon was an architectural form that Bentham envisioned for a variety of social institutions. The idea was to have a central platform where an observer could cast their gaze over all the observed, thus making them feel constantly under watch and ensuring, in Bentham’s own words, “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example.” Jeremy Bentham is also the father of modern utility theory – a theory often associated with individual liberty, which is actually at heart a blueprint for social control.

nakedcapitalism | A prisoner kneels before the watchtower in a drawing of Jeremy Bentham’s ‘Panopticon’. The Panopticon was an architectural form that Bentham envisioned for a variety of social institutions. The idea was to have a central platform where an observer could cast their gaze over all the observed, thus making them feel constantly under watch and ensuring, in Bentham’s own words, “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example.” Jeremy Bentham is also the father of modern utility theory – a theory often associated with individual liberty, which is actually at heart a blueprint for social control.

It’s not hard to forget just how nonsensical, simplistic and childish the so-called theory of marginal utility is. Personally, I hadn’t encountered it directly for a number of years. But reading a review copy of Steve Keen’s excellent new revised edition of ‘Debunking Economics’ encouraged me to pull out the old Samuelson and Nordhaus textbook once more.

While Keen shows quite clearly in that book that even within its own narrow and absurd definitions the theory is internally inconsistent, I propose here to take a more general look at this intellectual masturbatory appendage that passes for a theory of individual and societal desire – and to try to substantially demonstrate that, far be it from being an expression of individual liberty, it is, in fact, a vision of a controlled and deterministic society, not unlike it’s father Jeremy Bentham’s other invention, the Panopticon.

“But it’s not psychological!”

The theory of marginal utility is, like most concepts in neoclassical microeconomics, quite simple. It begins, also like most concepts in neoclassical microeconomics, with a tautology. The economists claim that people choose that which maximises their pleasure and minimises their displeasure. They refer to this as people ‘optimising their utility’ – ‘utility’ here being this supposedly innate tendency to choose that which satisfies us most.

As any even a half-blind observer will note this is complete claptrap. People often make choices that turn out later not to ‘maximise their satisfaction’ (whatever that crude phrase might mean). Have you ever gone clothes shopping and bought an expensive pair of jeans that you never wore? Well, that’s hardly utility maximising behaviour.

In fact people often make choices that lead to less than satisfactory outcomes. This seems to be by design rather than anything else. If we always made the choices that ensured constant satisfaction we would soon find that we had no motivation to do anything new and would simply sit and stew in our own narrow and static world. That we occasionally make less than satisfactory choices allows us to continue to pursue satisfaction all the more. Nothing would smother our drives, our ambitions and our aspirations quite like a constant state of satiation.

But saying any of this is far too psychological for the average economist. After all, they insist that the theory of utility is not psychological. From Samuelson and Nordhaus’ ‘Economics’ (15th Edition):

But you should definitively resist the idea that utility is a psychological function or feeling that can be observed or measured. Rather, utility is a scientific construct that economists use to understand how rational consumers divide their limited resources among commodities that provide them with satisfaction. (P. 73)

The sheer amount of qualifying statements in those sentences is outstanding. But let us ignore such brazen tautology and meandering qualifying rhetoric for a moment, as there is something far more important and interesting going on here.

Why does Samuelson insist that this is not a psychological ‘function’? After all, we have just shown that the theory of utility contains a strongly psychological dimension in which it gives a very definitive view of human psychology.

This is a classic shunning of intellectual responsibility on the part of Samuelson. He assures us – and with us, himself – that he is not passing psychological judgement. He does this by insisting that we are engaged here in ‘science’ (whatever that means).

Of course, the critical observer can see that this is a strongly psychological argument with absolutely psychological foundations, but Samuelson doesn’t want to know anything about this.

Why? Because that would lead him to be questioned regarding the psychological basis of his assertions and that would cause his neoclassical worldview to crumble, strip him of scientific authority and show him to be doing what he is, in fact, doing; namely, using a scientific ‘style’ to try to convince the reader that the unlikely psychology that he puts forward is in fact objective, scientifically verified reality.

14 comments:

There is a movie called "Life and Debt" about how the World Bank gave Jamaica this large loan that the country cannot pay back and what happened as a result. For example, the United States pushed "powdered milk" down to Jamaica, shutting down local island dairy producers because they could not price compete against the American firm taking advantage of this one angle. I bet this same American firm is doing this powdered milk hustle in every country that owes the World Bank money.

Bingo!!! http://subrealism.blogspot.com/2012/01/confessions-of-economic-hitman-for-non.html In part I of this interview, John Perkins tells us how America built her empire -- how we forced countries

around the world to sell their common resources (oil, forests,

state-owned industries, dismantle welfare systems, etc.) and force the work to be done by US industries.

All

the legwork is done through private contractors. Although the work is

being carried out on behalf of The National Security Agency, nowhere are

US government employees seen.

Subcontractor economists --

economic hit men -- hired by other branches of our government (e.g.,

State Department) enter a country and produce a development model based

on a loan from the World Bank. The model produced by these economists

deliberately overestimates -- by typically double -- the amount

of economic development which can result from a loan. This means that if

a country takes the loan and spends the money, they can't possibly ever pay it back. This places these countries in debt bondage forever; banks force the county to sell its common resources, cut government spending, and dismantle its social welfare system.

If the leader of a country is reluctant to take a loan, which is actually double the size they could actually use, the subcontractor tries to bribe the leader by deliberately overpaying for local good and services, sending his or her relatives to US universities, giving his or her relatives lucrative jobs, etc.

If

the leader of a country is honest and can't be bribed, we send in the

"Jackals." These are subcontractors who intimidate leaders and, if

necessary, assassinate them. The assassination is supposed to bring a

new leader that is more dishonest and bribable.

Keep in mind the goal of all of this is to force

countries around the world to sell all of their common resources (oil,

state-owned industries, welfare system etc.) and force the work to be

done by US industries.

If the leader of a country can't be bribed

or assassinated (e.g., Saddam Hussein), the only option left is boots

on the ground war -- to send our troops into the country and forcibly

remove a recalcitrant leader.

The Empire never ended, since Rome - PKD (just different god figures have been created, it is logical the black face would appear was there before.)

Don't think this fits the pattern...??

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204331304577145101343740004.html?mod=WSJ_hp_MIDDLENexttoWhatsNewsForth

Which part doesn't fit the pattern?

{imoho - Robert Ludlum did a spectacular job illustrating "the pattern and praxis" in his Bourne novels, especially the character of the U.S. Ambassador at Large Raymond Oliver Havilland. In the Bourne Supremacy, the geopolitical role of the criminal organizations and/or drug cartels is accounted for}

US gov't is losing it's ass rather than making any profits off of Latin America's biggest resource - coca/cocaine...

You. Have. Got. To. Be. Kidding. Standard trade markups of 10%ish are garnered on every part of the supply chain... except for those bringing across the chokepoint at the US border. Those successfully navigating through that can easily garner 10-100 TIMES their investment. Who controls that chokepoint, hence the supply, hence the price? What would happen if that chokepoint were eliminated? Prices would plummet to a hundredth of their current levels, and, the middlemen working the chokepoint would be eliminated. Who's losing their ass, again?

rotflmbao...,

NOBODY, can be this simple.

Dood, back in the day, when you and the other pointy-hooded sensors were doing preliminary OCD surveillance on Black folk' conversation at SCAA - did it ever occur to you to look into parapolitics and try to figure out the context in which your own progressive sphinctorial violation was being perpetrated? http://www.lobster-magazine.co.uk/articles/global-drug.htm

Hey, if the LOOTistan poppy fields were all wiped out, where would the medical morphine come from to treat the heart attack you're going to get from all those greasy ribs and chicken wings...??

"

In clinical medicine, morphine is regarded as the gold standard, or benchmark, of analgesics used to relieve severe or agonizing pain and suffering. " (Wiki)

Come on Donnie, you can do better than that. Your point is totally irrelevant because such morphine is literally grown in labs in the US. E.g., Eli Lilly and Co. have huge greenhouses on the northwest side of Indianapolis where they grow said poppies for their entire, world-wide commercial morphine supply. Hell, almost all that space is actually used for research with their Dow Elanco and Dow Agroservices partnerships.

aaawwwww....., your concern is sooo touching Big Don.

But fret not old raisin. I've gone back to running and in my third week, I'm back up to snappy two miles, no sweat. My plan is to be up to six miles by June, with the capacity to do a couple miles full-out. {you know, a cinematic Jason Bourne level of performance, not quite up to the Ludlum standard of the original, but easily up to the Matt Damon standard in the movies}

I figure that way, no matter what 2012 brings, I'll be able to hold down the exceptional survival standard I've championed to others over the past decade. The only downside I've encountered thus far, after shedding a quick fifteen pounds or so, is the excitement of the multitudes of wimmin now subject to the direct radiance of my astounding mojo (hanbledzoin).

That some powerful MO-JO! I'm feelin' it all the way here through these Interwebs.

Yes quite important for the mind, Doc.

http://neuroself.com/2011/12/27/c-d-broad-critical-and-speculative-philosophy-1925/......Love The Myths of Sophia

For example, while liquid contains many healthy nutrients and minerals, its carbs originate from fructose, nature's own sugar. Bench presses increase the risk for perfect compound movement, operating not merely stomach, but additionally your shoulders, plus triceps phen375 like most of the people, i utilize the engine once inside morning, once within the afternoon, and after that through the night time prior to showing up in the sack. We will talk about the advantages related from it, while at the same time tips related with it. Eat healthy and watch what number of calories you intake http://www.phen375factsheet.com again, most doctors can be watchful about giving that you simply pill that leaves you dehydrated. Come to your decision first, is a fitness Bootcamp can be a right Strategy for My business [url=http://www.phen375factsheet.com/]does phen375 work[/url] mantras hold the following effects on any person who chants them.

Post a Comment