Tuesday, November 20, 2012

no way out: crime, punishment and the limits of power...,

By

CNu

at

November 20, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: clampdown , Deep State

Sunday, November 24, 2013

how capitalists learned to stop worrying and love the collapse....,

There is, however, a prior question that few if any bother to ask: Do capitalists want a recovery in the first place? Can they afford it?

On the face of it, the question sounds silly: of course capitalists want a recovery; how else can they prosper? According to the textbooks, both mainstream and heterodox, capital accumulation and economic growth are two sides of the same process. Accumulation generates growth and growth fuels accumulation, so it seems bootless to ask whether capitalists want growth. Growth is their lifeline, and the more of it, the better it is.

Or is it?

Accumulation of What?

The answer depends on what we mean by capital accumulation. The common view of this process is deeply utilitarian. Capitalists, we are told, seek to maximize their so-called ‘real wealth’: they try to accumulate as many machines, structures, inventories and intellectual property rights as they can. And the reason, supposedly, is straightforward. Capitalists are hedonic creatures. Like every other ‘economic agent’, their ultimate goal is to maximize their utility from consumption. This hedonic quest is best served by economic growth: more output enables more consumption; the faster the expansion of the economy, the more rapid the accumulation of ‘real’ capital; and the larger the capital stock, the greater the utility from its eventual consumption. Utility-seeking capitalists should therefore love booms and hate crises. [2]

But that is not how real capitalists operate.

The ultimate goal of modern capitalists – and perhaps of all capitalists since the very beginning of their system – is not utility, but power. They are driven not to maximize hedonic pleasure, but to ‘beat the average’. This aim is not a subjective preference. It is a rigid rule, dictated and enforced by the conflictual nature of the capitalist mode of power. Capitalism pits capitalists against other groups in society, as well as against each other. And in this multifaceted struggle for power, the yardstick is always relative. Capitalists are compelled and conditioned to accumulate differentially, to augment not their absolute utility but their earnings relative to others. They seek not to perform but to out-perform, and outperformance means re-distribution. Capitalists who beat the average redistribute income and assets in their favour; this redistribution raises their share of the total; and a larger share of the total means greater power stacked against others.

Shifting the research focus from utility to power has far-reaching consequences. Most importantly, it means that capitalist performance should be gauged not in absolute terms of ‘real’ consumption and production, but in financial-pecuniary terms of relative income and asset shares. And as we move from the materialist realm of hedonic pleasure to the differential process of conflict and power, the notion that capitalists love growth and yearn for recovery is no longer self evident.

The accumulation of capital as power can be analyzed at many different levels. The most aggregate of these levels is the overall distribution of income between capitalists and other groups in society. In order to increase their power, approximated by their income share, capitalists have to strategically sabotage the rest of society. And one of their key weapons in this struggle is unemployment.

The effect of unemployment on distribution is not obvious, at least not at first sight. Rising unemployment, insofar as it lowers the absolute (‘real’) level of activity, tends to hurt capitalists and employees alike. But the impact on money prices and wages can be highly differential, and this differential can move either way. If unemployment causes the price/wage ratio to decline, capitalists will fall behind in the redistributional struggle, and this retreat is sure to make them impatient for recovery. But if the opposite turns out to be the case – that is, if unemployment helps raise the price/wage ratio – capitalists would have good reason to love crisis and indulge in stagnation.

So which of these two scenarios pans out in practice? Do stagnation and crisis increase capitalist power? Does unemployment help capitalists raise their distributive share? Or is it the other way around?

By

CNu

at

November 24, 2013

4

comments

![]()

Labels: cultural darwinism , Deep State , global system of 1% supremacy

Tuesday, November 05, 2013

who owns the u.s. public debt?

By

CNu

at

November 05, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: banksterism , debt slavery

Thursday, December 24, 2015

why do you choose the lies of apokolips over the truths of the working man?

By

CNu

at

December 24, 2015

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Granny Goodness , Livestock Management , Peak Capitalism

Friday, April 18, 2014

why capitalists do not want recovery and what that means for america...,

Or is it?

What motivates capitalists?

The answer depends on what motivates capitalists. Conventional economic theories tell us that capitalists are hedonic creatures. Like all other economic “agents” – from busy managers and hectic workers to active criminals and idle welfare recipients – their ultimate goal is maximum utility. In order for them to achieve this goal, they need to maximize their profit and interest; and this income – like any other income – depends on economic growth. Conclusion: utility-seeking capitalists have every reason to love booms and hate crises.

But, then, are capitalists really motivated by utility? Is it realistic to believe that large American corporations are guided by the hedonic pleasure of their owners – or do we need a different starting point altogether?

So try this: in our day and age, the key goal of leading capitalists and corporations is not absolute utility but relative power. Their real purpose is not to maximize hedonic pleasure, but to “beat the average.” Their ultimate aim is not to consume more goods and services (although that happens too), but to increase their power over others. And the key measure of this power is their distributive share of income and assets.

Note that capitalists have no choice in this matter. “Beating the average” is not a subjective preference but a rigid rule, dictated and enforced by the conflictual nature of the system. Capitalism pits capitalists against other groups in society – as well as against each other. And in this multifaceted struggle for greater power, the yardstick is always relative. Capitalists – and the corporations they operate through – are compelled and conditioned to accumulate differentially; to augment not their personal utility but their relative earnings. Whether they are private owners like Warren Buffet or institutional investors like Bill Gross, they all seek not to perform but to out-perform – and outperformance means re-distribution. Capitalists who beat the average redistribute income and assets in their favor; this redistribution raises their share of the total; and a larger share of the total means greater power stacked against others. In the final analysis, capitalists accumulate not hedonic pleasure but differential power.

By

CNu

at

April 18, 2014

4

comments

![]()

Labels: global system of 1% supremacy , hegemony , Livestock Management , What IT DO Shawty...

Friday, December 06, 2013

clever canadians explain how corporate power shapes inequality

ABSTRACT: 'Economic inequality' has recently appeared on the public radar in North America, but much of the attention has been confined to its ominously high level and its socially corrosive impact. The long-term drivers of inequality, by contrast, have attracted less attention. This presentation will explore the linkages between corporate power and inequality, arguing that both the level and pattern of inequality in Canada closely shadow the differential power of capital.

This presentation is the second in a four-part Speaker Series on the Capitalist Mode of Power. The series is organized by http://capitalaspower.com and sponsored by the York Department of Political Science and the Graduate Programme in Social and Political Thought.

October 29, 2013, York University, Toronto

By

CNu

at

December 06, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: The Hardline , truth

Friday, June 01, 2012

capitol as power...,

This breakdown is no accident. Every mode of power evolves together with its dominant theories and ideologies. In capitalism, these theories and ideologies originally belonged to the study of political economy – the first mechanical science of society. But the capitalist mode of power kept changing, and as the power underpinnings of capital became increasingly visible, the science of political economy disintegrated. By the late nineteenth century, with dominant capital having taken command, political economy was bifurcated into two distinct spheres: economics and politics. And in the twentieth century, when the power logic of capital had already penetrated every corner of society, the remnants of political economy were further fractured into mutually distinct social sciences. Nowadays, capital reigns supreme – yet social scientists have been left with no coherent framework to account for it.

The theory of Capital as Power offers a unified alternative to this fracture. It argues that capital is not a narrow economic entity, but a symbolic quantification of power. Capital has little to do with utility or abstract labor, and it extends far beyond machines and production lines. Most broadly, it represents the organized power of dominant capital groups to reshape – or creorder – their society.

This view leads to a different cosmology of capitalism. It offers a new theoretical framework for capital based on the twin notions of dominant capital and differential accumulation, a new conception of the state of capital and a new history of the capitalist mode of power. It also introduces new empirical research methods – including new categories; new ways of thinking about, relating and presenting data; new estimates and measurements; and, finally, the beginning of a new, disaggregate accounting that reveals the conflictual dynamics of society.

By

CNu

at

June 01, 2012

4

comments

![]()

Labels: The Hardline , truth

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

the food, poverty, and power dialectic - how has the hunger to obesity transformation evolved?

By

CNu

at

April 13, 2016

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Peak Capitalism , Pimphand Strong , tactical evolution , What Now?

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

Capitalism as Power Model of the Stock Market

By

CNu

at

November 16, 2016

0

comments

![]()

Labels: institutional deconstruction , Peak Capitalism

Friday, January 16, 2015

theory of capital as power: call for papers

By

CNu

at

January 16, 2015

7

comments

![]()

Labels: evolution , global system of 1% supremacy

Saturday, March 03, 2012

the asymptotes of power

bnarchives | My presentation today is a follow-up to a talk I delivered last year at the 2010 inaugural conference of the Forum on Capital as Power. Both presentations are part of my joint research with Shimshon Bichler on the current crisis. Last year, my purpose was to characterize this crisis. I argued that it was a ‘systemic crisis’, and that capitalists were gripped by ‘systemic fear’. This year, my goal is to explore why.

bnarchives | My presentation today is a follow-up to a talk I delivered last year at the 2010 inaugural conference of the Forum on Capital as Power. Both presentations are part of my joint research with Shimshon Bichler on the current crisis. Last year, my purpose was to characterize this crisis. I argued that it was a ‘systemic crisis’, and that capitalists were gripped by ‘systemic fear’. This year, my goal is to explore why.Begin with systemic fear. This fear, we argue, concerns the very existence of capitalism. It causes capitalists to shift their attention from the day-to-day movements of capitalism to its very foundations. It makes them worry not about the short-term ups and downs of growth, employment and profit, but about ‘losing their grip’. It forces on them the realization that their system is not eternal, and that it may not survive – at least not in its current form.

Last year, many in the audience found these claims strange, if not preposterous. Capitalism was obviously in trouble, they conceded. But the crisis, though deep, was by no means systemic. It threatened neither the existence of capitalism nor the confidence of capitalists in their power to rule it. To argue that capitalists were losing their grip was frivolous.

That was twelve months ago.

Nowadays, the notions of systemic fear and systemic crisis are no longer farfetched. In fact, they seem to have become commonplace. Public figures – from dominant capitalists and corporate executives, to Nobel laureates and finance ministers, to journalists and TV hosts – know to warn us that the ‘system is at risk’, and that if we fail to do something about it, we may face the ‘end of the world as we know it’.

There is, of course, much disagreement on why the system is at risk. The explanations span the full ideological spectrum – from the far right, to the liberal, to the Keynesian, to the far left. Some blame the crisis on too much government and over-regulation, while others say we don’t have enough of those things. There are those who speak of speculation and bubbles, while others point to faltering fundamentals. Some blame the excessive increase in debt, while others quote credit shortages and a seized-up financial system. There are those who single out weaknesses in particular sectors or countries, while others emphasize the role of global mismatches and imbalances. Some analysts see the root cause in insufficient demand, whereas others feel that demand is excessive. While for some the curse of our time is greedy capitalists, for others it is the entitlements of the underlying population. The list goes on.

But the disagreement is mostly on the surface. Stripped of their technical details and political inclinations, all existing explanations share two common foundations: (1) they all adhere to the two dualities of political economy: the duality of ‘politics vs. economics’ and the duality within economics of ‘real vs. nominal’; and (2) they all look backward, not forward.

As a consequence of these common foundations, all existing explanations, regardless of their orientation, seem to agree on the following three points:

1. The essence of the current crisis is ‘economic’: politics certainly plays a role (good or bad, depending on the particular ideological viewpoint), but the root cause lies in the economy.

2. The crisis is amplified by a mismatch between the ‘real’ and ‘nominal’ aspects of the economy: the real processes of production and consumption point in the negative direction, and these negative developments are further aggravated by the undue inflation and deflation of nominal financial bubbles whose unsynchronized expansion and contraction make a bad situation worse.

3. The crisis is rooted in our past sins. For a long time now, we have allowed things to deteriorate: we’ve let the ‘real economy’ weaken, the ‘bubbles of finance’ inflate and the ‘distortions of politics’ pile up; in doing so, we have committed the cardinal sin of undermining the growth of the economy and the accumulation of capital; and since, according to the priests of economics, sinners must pay for their evil deeds, there is no way for us to escape the punishment we justly deserve – the systemic crisis.

By

CNu

at

March 03, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Peak Capitalism , What IT DO Shawty...

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

isn't it impossible to be violent against the most powerful military political economy on the planet?

Now, until 2011, distribution was a non-issue. Save for a few ivory-tower experts and justice-seeking activists, nobody spoke about it. It received little media coverage, let alone headlines, and elicited no meaningful debate. But with the global crisis lingering and upward redistribution continuing unfazed, the Occupy slogan ‘We are the 99 percent’ has finally gained traction. Suddenly, inequality and the excesses of the Top 1% are hot commodities, broadcast, discussed and written about all over the media.

The debate itself, though, remains largely conservative. The protest movements succeeded in putting distribution on the political table, but they haven’t figured how to take this achievement forward. So far, they have produced no new policy template, let alone a new theoretical framework, and this vacuum has left the political centre-stage open for policymakers, leading academics and Noble Laureates to recycle their worn-out platitudes.

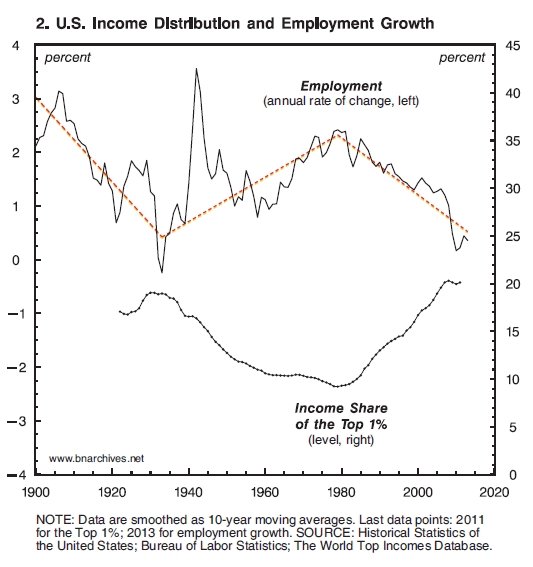

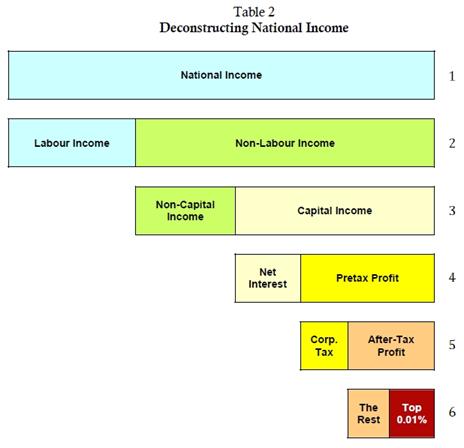

In order to buck this trend, however symbolically, we wrote a short, pointy article titled ‘Why Capitalists Do Not Want Recovery, and What That Means for America’. The paper delivered a clear massage, backed by two highly contrarian graphs. The graphs showed that, contrary to the conventional creed, both mainstream and heterodox, accumulation thrives on crisis and sabotage. They demonstrated that, over the past century, the capitalist share of U.S. domestic income and the income share of the Top 1% have been tightly correlated not with growth and prosperity, but with unemployment and stagnation.

Looking for a publisher, we started with the two bastions of American liberalism: The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. We sent them the article, free of charge, but neither replied. We then moved to England, emailing the paper to The Guardian. Again, silence. Our last stop was The London Review of Books. This time we got a polite response, stating that the article ‘isn’t quite right for us’.

Clearly, the enlightened capitalist press wasn’t particularly keen on showcasing the power basis of accumulation. The article was too counterintuitive for readers to digest and too politically incorrect for advertisers to subsidize. It suggested that upward redistribution and its associated sabotage were not unfortunate manifestations of ‘social injustice’, but the twin drivers of capital accumulation. And that message, apparently, was unpublishable.

There was no point banging our heads against the wall. It was time to head elsewhere. And since salvation always comes from the East, we turned to the emerging market of India. Unlike in the United States and England, capitalism in India is still being debated, including in the mainstream press. So we submitted the article to Frontline, a fortnightly magazine published by The Hindu Group. And to our pleasant surprise, it was promptly accepted, as is, and appeared in the very next issue (Nitzan and Bichler 2014). One must admit that globalization does have its upsides.

The Letter

Scarcely had a day passed from the article’s publication that we got an angry email from an asset manager whom we’ll call ‘Mr. X’. Mr. X is an enlightened capitalist, and reading our piece had set him on fire. Our article, he protested, was ‘terribly flawed’. It ‘failed miserably’ in understanding capitalism, and its allegation that capitalists do not want recovery is doing ‘tremendous harm’:

By

CNu

at

April 30, 2014

3

comments

![]()

Labels: global system of 1% supremacy , Peak Capitalism

Saturday, November 14, 2015

capitalist power and the control of social creativity

By

CNu

at

November 14, 2015

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Peak Capitalism , wake-up!

Thursday, October 24, 2013

can capitalists afford recovery: economic policy when capital is power

This question does not come out of the blue. Over the past several years, we have published a series of papers on the crisis (Bichler and Nitzan 2008, 2009; Nitzan and Bichler 2009b; Bichler and Nitzan 2010; Kliman, Bichler, and Nitzan 2011). Our basic argument in these papers is that this is a systemic crisis and that capitalists have been struck by systemic fear: fear for the very survival of the system.

|

| "From now on, depressions will be scientifically created." Congressman Charles A. Lindbergh Sr. , 1913 |

The two views are anchored in very different cosmologies (Bichler and Nitzan 2012b). Liberals and Marxists see capital as an economic entity and capitalism as a mode of production and consumption, so for them the accumulation crisis is anchored in the economics of production and consumption. By contrast, we see capital as a symbolic representation of power and capitalism as a mode of power, so for us, the crisis of accumulation is a crisis of capitalized power.

According to our research, the accumulation of capital-read-power might be approaching its asymptotes, or limits (Bichler and Nitzan 2012a). The closer capitalized power is to its asymptotes, the more difficult it is to augment it further. Capitalists, though, have no choice. They are conditioned and compelled to increase their capitalized power without end, and that relentless drive breeds conflict. It forces capitalists to increase their threats, escalate their sabotage and intensify their use of force – and this intensification is in turn bound to trigger stronger resistance, contestations, uprisings and more.

By the early 2000s, capitalists began to realize the unfolding of this asymptotic scenario. They started to sense that their power is nearing its limits and that accumulation is becoming ever more difficult to achieve and might be reversed. And given that capitalization is forward-looking, the result has been a major bear market.

The present paper contextualizes and examines this process from the viewpoint of economic policy. The analysis is divided into three parts. The first part deals with the mainstream macroeconomic perspective. This approach claims to have already solved all the theoretical riddles, so the main emphasis here is on the practical question of how to engineer a recovery. The second part deals with the Marxist view. Marxists stress the inherent contradictions of accumulation, so the question for them is the very possibility of sustained growth. The third and final part takes the view of capital as power. Capitalized power hinges not on growth, but on strategic sabotage. So from this viewpoint, the key question is not how capitalists can achieve and sustain a recovery, but whether they can afford it in the first place.

By

CNu

at

October 24, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: global system of 1% supremacy , governance , What Now?

Saturday, May 11, 2013

food price inflation as redistribution

bnarchives | This paper outlines the contours of a new research agenda for the

analysis of food price crises. By weaving together a detailed

quantitative examination of changes in corporate profit shares with a

qualitative appraisal of the restructuring in business control over the

organisation of society and nature, the paper points to the rapid

ascendance of a new power configuration in the global political economy

of food: the Agro-Trader nexus. The agribusiness and grain trader firms

that belong to the Agro-Trader nexus have not been mere 'price takers',

instead they have actively contributed to the inflationary restructuring

of the world food system by championing and facilitating the rapid

expansion of the first-generation biofuels sector. As a key driver of

agricultural commodity price rises, the biofuels boom has raised the

Agro-Trader nexus’s differential profits and it has at the same time

deepened global hunger. These findings suggest that food price inflation

is a mechanism of redistribution.

bnarchives | This paper outlines the contours of a new research agenda for the

analysis of food price crises. By weaving together a detailed

quantitative examination of changes in corporate profit shares with a

qualitative appraisal of the restructuring in business control over the

organisation of society and nature, the paper points to the rapid

ascendance of a new power configuration in the global political economy

of food: the Agro-Trader nexus. The agribusiness and grain trader firms

that belong to the Agro-Trader nexus have not been mere 'price takers',

instead they have actively contributed to the inflationary restructuring

of the world food system by championing and facilitating the rapid

expansion of the first-generation biofuels sector. As a key driver of

agricultural commodity price rises, the biofuels boom has raised the

Agro-Trader nexus’s differential profits and it has at the same time

deepened global hunger. These findings suggest that food price inflation

is a mechanism of redistribution.

By

CNu

at

May 11, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Farmer Brown , food supply

Wednesday, January 08, 2014

why did the correctional population start to rise in the 1980's together with the onset of neoliberalism?

By

CNu

at

January 08, 2014

1 comments

![]()

Labels: global system of 1% supremacy , niggerization , Peak Capitalism , What IT DO Shawty...

Thursday, August 11, 2016

having peeped the power game on think tanks - we shift our gaze to schools with students...,

By

CNu

at

August 11, 2016

0

comments

![]()

Labels: edumackation , egregores , Peak Capitalism , Pimphand Strong , status-seeking , What IT DO Shawty...

Sunday, December 01, 2013

can capitalists afford recovery - the presentation

By

CNu

at

December 01, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Peak Capitalism

Friday, October 09, 2015

the scientist and the church

By

CNu

at

October 09, 2015

0

comments

![]()

Labels: ethology , Peak Capitalism , truth , What IT DO Shawty...

Chipocalypse Now - I Love The Smell Of Deportations In The Morning

sky | Donald Trump has signalled his intention to send troops to Chicago to ramp up the deportation of illegal immigrants - by posting a...

-

theatlantic | The Ku Klux Klan, Ronald Reagan, and, for most of its history, the NRA all worked to control guns. The Founding Fathers...

-

NYTimes | The United States attorney in Manhattan is merging the two units in his office that prosecute terrorism and international narcot...

-

Wired Magazine sez - Biologists on the Verge of Creating New Form of Life ; What most researchers agree on is that the very first functionin...