Rolling Stone | I have a confession to make. At first, I misunderstood Occupy Wall Street.

The first few times I went down to Zuccotti Park, I came away with mixed feelings. I loved the energy and was amazed by the obvious organic appeal of the movement, the way it was growing on its own. But my initial impression was that it would not be taken very seriously by the Citibanks and Goldman Sachs of the world. You could put 50,000 angry protesters on Wall Street, 100,000 even, and Lloyd Blankfein is probably not going to break a sweat. He knows he's not going to wake up tomorrow and see Cornel West or Richard Trumka running the Federal Reserve. He knows modern finance is a giant mechanical parasite that only an expert surgeon can remove. Yell and scream all you want, but he and his fellow financial Frankensteins are the only ones who know how to turn the machine off.

That's what I was thinking during the first few weeks of the protests. But I'm beginning to see another angle. Occupy Wall Street was always about something much bigger than a movement against big banks and modern finance. It's about providing a forum for people to show how tired they are not just of Wall Street, but everything. This is a visceral, impassioned, deep-seated rejection of the entire direction of our society, a refusal to take even one more step forward into the shallow commercial abyss of phoniness, short-term calculation, withered idealism and intellectual bankruptcy that American mass society has become. If there is such a thing as going on strike from one's own culture, this is it. And by being so broad in scope and so elemental in its motivation, it's flown over the heads of many on both the right and the left.

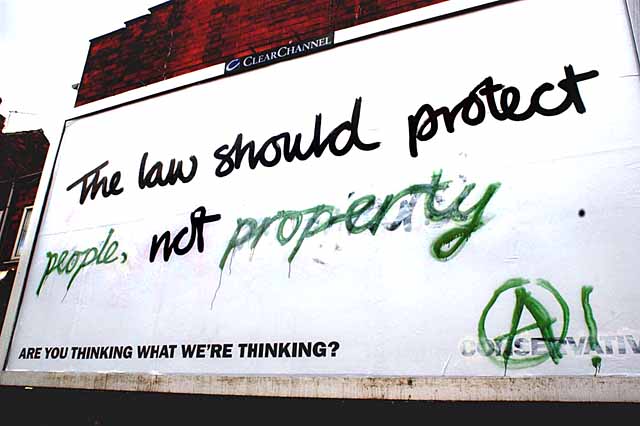

The right-wing media wasted no time in cannon-blasting the movement with its usual idiotic clichés, casting Occupy Wall Street as a bunch of dirty hippies who should get a job and stop chewing up Mike Bloomberg's police overtime budget with their urban sleepovers. Just like they did a half-century ago, when the debate over the Vietnam War somehow stopped being about why we were brutally murdering millions of innocent Indochinese civilians and instead became a referendum on bralessness and long hair and flower-child rhetoric, the depraved flacks of the right-wing media have breezily blown off a generation of fraud and corruption and market-perverting bailouts, making the whole debate about the protesters themselves – their hygiene, their "envy" of the rich, their "hypocrisy."

The protesters, chirped Supreme Reichskank Ann Coulter, needed three things: "showers, jobs and a point." Her colleague Charles Krauthammer went so far as to label the protesters hypocrites for having iPhones. OWS, he said, is "Starbucks-sipping, Levi's-clad, iPhone-clutching protesters [denouncing] corporate America even as they weep for Steve Jobs, corporate titan, billionaire eight times over." Apparently, because Goldman and Citibank are corporations, no protester can ever consume a corporate product – not jeans, not cellphones and definitely not coffee – if he also wants to complain about tax money going to pay off some billionaire banker's bets against his own crappy mortgages.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the political spectrum, there were scads of progressive pundits like me who wrung our hands with worry that OWS was playing right into the hands of assholes like Krauthammer. Don't give them any ammunition! we counseled. Stay on message! Be specific! We were all playing the Rorschach-test game with OWS, trying to squint at it and see what we wanted to see in the movement. Viewed through the prism of our desire to make near-term, within-the-system changes, it was hard to see how skirmishing with cops in New York would help foreclosed-upon middle-class families in Jacksonville and San Diego.

What both sides missed is that OWS is tired of all of this. They don't care what we think they're about, or should be about. They just want something different.

We're all born wanting the freedom to imagine a better and more beautiful future. But modern America has become a place so drearily confining and predictable that it chokes the life out of that built-in desire. Everything from our pop culture to our economy to our politics feels oppressive and unresponsive. We see 10 million commercials a day, and every day is the same life-killing chase for money, money and more money; the only thing that changes from minute to minute is that every tick of the clock brings with it another space-age vendor dreaming up some new way to try to sell you something or reach into your pocket. The relentless sameness of the two-party political system is beginning to feel like a Jacob's Ladder nightmare with no end; we're entering another turn on the four-year merry-go-round, and the thought of having to try to get excited about yet another minor quadrennial shift in the direction of one or the other pole of alienating corporate full-of-shitness is enough to make anyone want to smash his own hand flat with a hammer.

If you think of it this way, Occupy Wall Street takes on another meaning. There's no better symbol of the gloom and psychological repression of modern America than the banking system, a huge heartless machine that attaches itself to you at an early age, and from which there is no escape. You fail to receive a few past-due notices about a $19 payment you missed on that TV you bought at Circuit City, and next thing you know a collector has filed a judgment against you for $3,000 in fees and interest. Or maybe you wake up one morning and your car is gone, legally repossessed by Vulture Inc., the debt-buying firm that bought your loan on the Internet from Chase for two cents on the dollar. This is why people hate Wall Street. They hate it because the banks have made life for ordinary people a vicious tightrope act; you slip anywhere along the way, it's 10,000 feet down into a vat of razor blades that you can never climb out of.

That, to me, is what Occupy Wall Street is addressing. People don't know exactly what they want, but as one friend of mine put it, they know one thing: FUCK THIS SHIT! We want something different: a different life, with different values, or at least a chance at different values.

USAToday | One in 45 children in the USA — 1.6 million children — were living on the street, in homeless shelters or motels, or doubled up with other families last year, according to the National Center on Family Homelessness.

USAToday | One in 45 children in the USA — 1.6 million children — were living on the street, in homeless shelters or motels, or doubled up with other families last year, according to the National Center on Family Homelessness.