paecon | In a previous issue of the Review, both Thomas Wells and Bruce Elmslie argue that I got it wrong when I pointed out in “Free Enterprise and the Economics of Slavery” that in The Wealth of Nations, Smith treated slaves as property. I argued that since they were property—one could buy and sell them—one could ignore their human misery. I used Smith, as well as John Locke, to illustrate this peculiar Anglo-American tradition of basing freedom (free enterprise) on property and property rights. (On the European continent, freedom was generally based on the human will (Rousseau) or the moral will (Kant). So, did Smith treat slaves as property in The Wealth of Nations or did he not?

paecon | In a previous issue of the Review, both Thomas Wells and Bruce Elmslie argue that I got it wrong when I pointed out in “Free Enterprise and the Economics of Slavery” that in The Wealth of Nations, Smith treated slaves as property. I argued that since they were property—one could buy and sell them—one could ignore their human misery. I used Smith, as well as John Locke, to illustrate this peculiar Anglo-American tradition of basing freedom (free enterprise) on property and property rights. (On the European continent, freedom was generally based on the human will (Rousseau) or the moral will (Kant). So, did Smith treat slaves as property in The Wealth of Nations or did he not?In Civilizing the Economy, where I provide more details about Smith’s treatment of slaves in The Wealth of Nations, I quote his comparison of the treatment of cattle and slaves:[1]

In all European colonies the culture of the sugarcane is carried on by negro slaves . . . . But the success of the cultivation which is carried on by means of cattle, depend very much upon the good management of those cattle; so the profit and success of that which is carried on by slaves, must depend equally upon the good management of those slaves, and in the good management of their slaves the French planters, I think it is generally allowed, are superior to the English.[2]

Comparing the management of cattle and of African slaves, of course, expresses the full meaning of “chattel slavery,” since chattel has the same root as cattle. Furthermore, just as cattle were treated as property, so were slaves.

Elmslie makes much of Smith’s argument that free labor, in most cases, is superior to slave labor. Smith does write this, but I think he is thinking about this much like one would think about getting the most from what one has purchased. As Patricia Werhane has pointed out, for Smith, labor is property. The difference between whether it is free or slave labor depends on who controls it. She writes:

Because that property [one’s productivity] is one’s own, to which one has a perfect right, and because productivity is exchangeable, one should be free to exchange this commodity, and others should be free to employ it. Thus one can sell one’s labor productivity (but not one’s strength and dexterity) without thereby selling oneself into serfdom. If one is not paid for one’s productivity, one’s property rights will be violated. Worse, because one’s productivity is an outcome of one’s own labor, if it is not recognized as an exchangeable commodity, one thereby will be treated as a slave.[3]

Slaves, in other words, were not free to exchange their labor, but were exchanged as labor. So when Smith argues that free labor is usually more productive than slave labor, he is merely calculating how to get the best return from one’s investment.

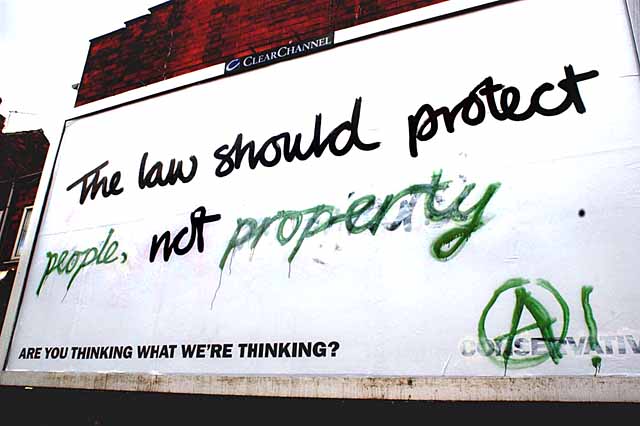

It is true that I do not give much credit to Smith’s statements against slavery in his other writings, although I do recognize them. The issue, however, is not Smith’s view of slavery as a moral philosopher, but his view as an economist. When he thinks economically, if we may call it this, he treats slaves as property. This is significant because we live in his legacy of this uncivil economics. In this tradition, we can be quite civil, in our religious, legal, and political life, but uncivil in our economic life. As we see the commercial gaining control over the civic today, we need not only to expose this tradition of treating people and the planet as property, but also to switch to a economics based on civic relations, rather than on one based on property and property relations.

0 comments:

Post a Comment