publicdomainreview | In April 1904, C. H. Hinton published The Fourth Dimension, a popular maths book based on concepts he had been developing since 1880 that sought to establish an additional spatial dimension to the three we know and love. This was not understood to be time as we’re so used to thinking of the fourth dimension nowadays; that idea came a bit later. Hinton was talking about an actual spatial dimension, a new geometry, physically existing, and even possible to see and experience; something that linked us all together and would result in a “New Era of Thought”. (Interestingly, that very same month in a hotel room in Cairo, Aleister Crowley talked to Egyptian Gods and proclaimed a “New Aeon” for mankind. For those of us who amuse ourselves by charting the subcultural backstreets of history, it seems as though a strange synchronicity briefly connected a mystic mathematician and a mathematical mystic — which is quite pleasing.)

|

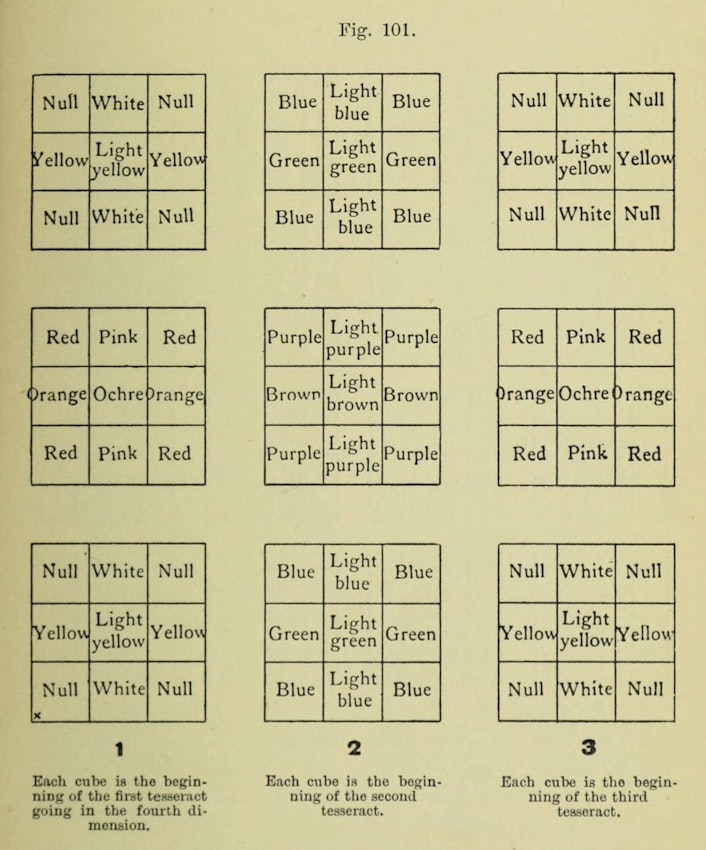

| The coloured cubes — known as "Tesseracts" — as depicted in the frontispiece to Hinton's The Fourth Dimension (1904) - Source. |

Hinton begins his book by briefly relating the history of higher dimensions and non-Euclidean maths up to that point. Surprisingly, for a history of mathematicians, it’s actually quite entertaining. Here is one tale he tells of János Bolyai, a Hungarian mathematician who contributed important early work on non-Euclidean geometry before joining the army:

It is related of him that he was challenged by thirteen officers of his garrison, a thing not unlikely to happen considering how differently he thought from everyone else. He fought them all in succession – making it his only condition that he should be allowed to play on his violin for an interval between meeting each opponent. He disarmed or wounded all his antagonists. It can be easily imagined that a temperament such as his was not one congenial to his military superiors. He was retired in 1833.

Janos Bolyai: Appendix. Shelfmark: 545.091. Table of Figures - Source.

Mathematicians have definitely lost their flair. The notion of duelling with violinist mathematicians may seem absurd, but there was a growing unease about the apparently arbitrary nature of "reality" in light of new scientific discoveries. The discoverers appeared renegades. As the nineteenth century progressed, the world was robbed of more and more divine power and started looking worryingly like a ship adrift without its captain. Science at the frontiers threatened certain strongly-held assumptions about the universe. The puzzle of non-Euclidian geometry was even enough of a contemporary issue to appear in Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov when Ivan discusses the ineffability of God:

But you must note this: if God exists and if He really did create the world, then, as we all know, He created it according to the geometry of Euclid and the human mind with the conception of only three dimensions in space. Yet there have been and still are geometricians and philosophers, and even some of the most distinguished, who doubt whether the whole universe, or to speak more widely, the whole of being, was only created in Euclid’s geometry; they even dare to dream that two parallel lines, which according to Euclid can never meet on earth, may meet somewhere in infinity… I have a Euclidian earthly mind, and how could I solve problems that are not of this world?

— Dostoevsky, Brothers Karamzov (1880), Part II, Book V, Chapter 3.

Well Ivan, to quote Hinton, “it is indeed strange, the manner in which we must begin to think about the higher world”. Hinton's solution was a series of coloured cubes that, when mentally assembled in sequence, could be used to visualise a hypercube in the fourth dimension of hyperspace. He provides illustrations and gives instructions on how to make these cubes and uses the word “tesseract” to describe the four-dimensional object.

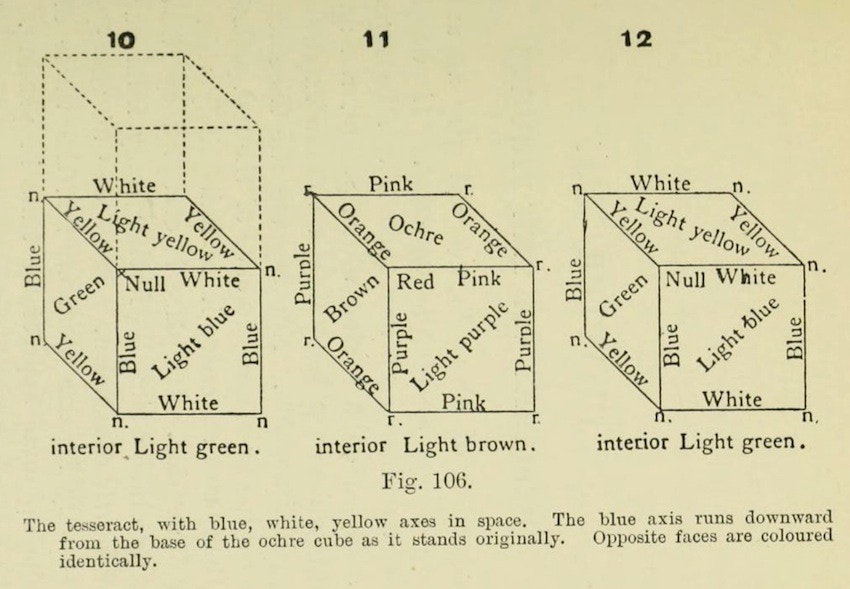

Diagram from Hinton's The Fourth Dimension (1904) - Source.

The term “tesseract”, still used today, might be Hinton’s most obvious legacy, but the genesis of the word is slightly cloudy. He first used it in an 1888 book called A New Era of Thought and initially used the spelling tessaract. In Greek, “τεσσάρα”, meaning “four”, transliterates to “tessara” more accurately than “tessera”, and -act likely comes from “ακτίνες” meaning "rays"; so Hinton’s use suggests the four rays from each vertex exhibited in a hypercube and neatly encodes the idea “four” into his four-dimensional polytope. However, in Latin, “tessera” can also mean “cube”, which is a plausible starting point for the new word. As is sometimes the case, there seems to be some confusion over the Greek or Latin etymology, and we’ve ended up with a bastardization. To confuse matters further, by 1904 Hinton was mostly using “tesseract” — I say mostly because the copies of his books I’ve seen aren’t entirely consistent with the spelling, in all likelihood due to a mere oversight in the proof-reading. Regardless, the later spelling won acceptance while the early version died with its first appearance.

Diagram from Hinton's The Fourth Dimension (1904) - Source.

Hinton also promises that when the visualisation is achieved, his cubes can unlock hidden potential. “When the faculty is acquired — or rather when it is brought into consciousness for it exists in everyone in imperfect form — a new horizon opens. The mind acquires a development of power”. It is clear from Hinton’s writing that he saw the fourth dimension as both physically and psychically real, and that it could explain such phenomena as ghosts, ESP, and synchronicities. In an indication of the spatial and mystical significance he afforded it, Hinton suggested that the soul was “a four-dimensional organism, which expresses its higher physical being in the symmetry of the body, and gives the aims and motives of human existence”. Letters submitted to mathematical journals of the time indicate more than one person achieved a disastrous success and found the process of visualising the fourth dimension profoundly disturbing or dangerously addictive. It was rumoured that some particularly ardent adherents of the cubes had even gone mad.

— H. P. Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu (1928)

0 comments:

Post a Comment