Wednesday, May 22, 2013

dry-land agriculture tough but not apocalyptic...,

By

CNu

at

May 22, 2013

1 comments

![]()

Labels: weather report

weather getting worse and our ability to forecast not keeping up..,

By

CNu

at

May 22, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Collapse Casualties , weather report

Tuesday, May 21, 2013

is higher education running AMOOC?

hakesedstuff | ABSTRACT: My discussion-list post “Evaluating the Effectiveness of College” at http://yhoo.it/16cJ7HO concerned the failure of U.S. higher education to emphasize student learning rather than the delivery of instruction [Barr and Tagg (1995)] at http://bit.ly/8XGJPc. In response, a correspondent asked me “Is There Some Hope In Coursera’s Pedagogical Foundations? ”

hakesedstuff | ABSTRACT: My discussion-list post “Evaluating the Effectiveness of College” at http://yhoo.it/16cJ7HO concerned the failure of U.S. higher education to emphasize student learning rather than the delivery of instruction [Barr and Tagg (1995)] at http://bit.ly/8XGJPc. In response, a correspondent asked me “Is There Some Hope In Coursera’s Pedagogical Foundations? ”

By

CNu

at

May 21, 2013

5

comments

![]()

Labels: edumackation , Livestock Management

why open online education is flourishing...,

By

CNu

at

May 21, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: edumackation , truth

Monday, May 20, 2013

a new book release from the people who brought you the Obamamandian Candidate....,

brookings | On May 20, the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings will host an event marking the release of Confronting Suburban Poverty in America, co-authored

by Elizabeth Kneebone and Alan Berube. They, along with some of the

nation’s leading anti-poverty experts, including Luis Ubiñas, president

of the Ford Foundation, and Bill Shore, founder and CEO of Share our

Strength, will join leading local innovators from across the country to

discuss a new metropolitan opportunity agenda for addressing suburban

poverty, how federal and state policymakers can deploy limited resources

to address a growing challenge, and why building on local solutions

holds great promise.

brookings | On May 20, the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings will host an event marking the release of Confronting Suburban Poverty in America, co-authored

by Elizabeth Kneebone and Alan Berube. They, along with some of the

nation’s leading anti-poverty experts, including Luis Ubiñas, president

of the Ford Foundation, and Bill Shore, founder and CEO of Share our

Strength, will join leading local innovators from across the country to

discuss a new metropolitan opportunity agenda for addressing suburban

poverty, how federal and state policymakers can deploy limited resources

to address a growing challenge, and why building on local solutions

holds great promise.

By

CNu

at

May 20, 2013

11

comments

![]()

Labels: Brookings , Obamamandian Imperative

the poor ye shall always have with you, in the burbs....,

kcstar.com | The number of impoverished people in America’s suburbs surged 64 percent in the past decade, creating for the first time a landscape in which the suburban poor outnumber the urban poor, a new report shows.

By

CNu

at

May 20, 2013

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Collapse Casualties

squeezed out of the affluent urban core...,

By

CNu

at

May 20, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: unintended consequences

nationwide establishment full-court press to get back on agenda....,

abqjournal | The Albuquerque metropolitan area ranks eighth in the country for

suburban poverty, according to a new book published by the Brookings

Institution.

abqjournal | The Albuquerque metropolitan area ranks eighth in the country for

suburban poverty, according to a new book published by the Brookings

Institution.

By

CNu

at

May 20, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: agenda , elite , establishment

Sunday, May 19, 2013

social psychology catching a right proper shit-hammering...,

|

| interestingly the New Yorker does not concur...., |

By

CNu

at

May 19, 2013

1 comments

![]()

Labels: accountability , Ass Clownery , What IT DO Shawty...

more making stuff up and getting busted for it....,

By

CNu

at

May 19, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: tricknology , unintended consequences

Saturday, May 18, 2013

ADHD is a fictitious disease - and - the vocabulary of psychiatry is now defined at all levels by the pharmaceutical industry

The alarmed critics of the Ritalin disaster are now getting support from an entirely different side. The German weekly Der Spiegel quoted in its cover story on 2 February 2012 the US American psychiatrist Leon Eisenberg, born in 1922 as the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, who was the “scientific father of ADHD” and who said at the age of 87, seven months before his death in his last interview:“ADHD is a prime example of a fictitious disease”

Since 1968, however, some 40 years, Leon Eisenberg’s “disease” haunted the diagnostic and statistical manuals, first as “hyperkinetic reaction of childhood”, now called “ADHD”. The use of ADHD medications in Germany rose in only eighteen years from 34 kg (in 1993) to a record of no less than 1760 kg (in 2011) – which is a 51-fold increase in sales! In the United States every tenth boy among ten year-olds already swallows an ADHD medication on a daily basis. With an increasing tendency.

When it comes to the proven repertoire of Edward Bernays, the father of propaganda, to sell the First World War to his people with the help of his uncle’s psychoanalysis and to distort science and the faith in science to increase profits of the industry – what about investigating on whose behalf the “scientific father of ADHD” conducted science? His career was remarkably steep, and his “fictitious disease” led to the best sales increases. And after all, he served in the “Committee for DSM V and ICD XII, American Psychiatric Association” from 2006 to 2009. After all, Leon Eisenberg received “the Ruane Prize for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Research. He has been a leader in child psychiatry for more than 40 years through his work in pharmacological trials, research, teaching, and social policy and for his theories of autism and social medicine”.

And after all, Eisenberg was a member of the “Organizing Committee for Women and Medicine Conference, Bahamas, November 29 – December 3, 2006, Josiah Macy Foundation (2006)”. The Josiah Macy Foundation organized conferences with intelligence agents of the OSS, later CIA, such as Gregory Bateson and Heinz von Foerster during and long after World War II. Have such groups marketed the diagnosis of ADHD in the service of the pharmaceutical market and tailor-made for him with a lot of propaganda and public relations? It is this issue that the American psychologist Lisa Cosgrove and others investigated in their study Financial Ties between DSM-IV Panel Members and the Pharmaceutical Industry7. They found that “Of the 170 DSM panel members 95 (56%) had one or more financial associations with companies in the pharmaceutical industry. One hundred percent of the members of the panels on ‘Mood Disorders’ and ‘Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders’ had financial ties to drug companies. The connections are especially strong in those diagnostic areas where drugs are the first line of treatment for mental disorders.” In the next edition of the manual, the situation is unchanged. “Of the 137 DSM-V panel members who have posted disclosure statements, 56% have reported industry ties – no improvement over the percent of DSM-IV members.” “The very vocabulary of psychiatry is now defined at all levels by the pharmaceutical industry,” said Dr Irwin Savodnik, an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California at Los Angeles.

By

CNu

at

May 18, 2013

4

comments

![]()

Labels: propaganda , tricknology , truth

Friday, May 17, 2013

I.Q. as a measure of intelligence is a myth...,

- We propose that human intelligence is composed of multiple independent components

- Each behavioral component is associated with a distinct functional brain network

- The higher-order “g” factor is an artifact of tasks recruiting multiple networks

- The components of intelligence dissociate when correlated with demographic variables

By

CNu

at

May 17, 2013

5

comments

![]()

Labels: neuromancy

next to nothing is known about the neurobiological mechanisms underlying individuality

By

CNu

at

May 17, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: neuromancy

Thursday, May 16, 2013

primates of park avenue...,

By

CNu

at

May 16, 2013

7

comments

![]()

Labels: ethology , global system of 1% supremacy

cheating and co-operating...,

By

CNu

at

May 16, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: ethology , killer-ape , tactical evolution , What IT DO Shawty...

Wednesday, May 15, 2013

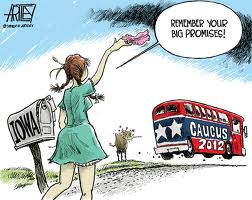

POTUS 2016 - remember where you heard it first!

By

CNu

at

May 15, 2013

4

comments

![]()

Labels: weather report

richwine says "he's no racist, and has a tough time spotting it, too"...,

By

CNu

at

May 15, 2013

5

comments

![]()

Labels: cultural darwinism , eugenics , What IT DO Shawty...

how misinformed ideas about profit are holding back the world's poor?

- Surely you can’t make money working with people who are so poor?

-

Don’t you feel like you are taking advantage of these people by making money from them?

- Wouldn’t charity do a better job of meeting their needs?

By

CNu

at

May 15, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: consumerism , Livestock Management , What IT DO Shawty...

phantom financial wealth, phantom carrying capacity and phantom democratic power...,

karlnorth | The Interdependence. Economic

activity at phantom carrying capacity depletes resources at a rate that

causes rising resource costs and decreasing profit margins in the

production of real wealth. The investor class therefore turns

increasingly to the production of credit as a source of profits. Credit

unsupported by the production of real wealth is stealing from the

future: it is phantom wealth. It also creates inflation, which is

stealing from the purchasing power of income in the present. Protected

from the masses by the illusion of democracy, government facilitates the

unlimited production of credit and the continued overshoot of real

carrying capacity. This causes inflation and permanently rising costs of

raw materials. To divert public attention from the resultant declining

living standard of the laboring classes, government dispenses rigged

statistics and fake news of continued growth to project the illusion of

economic health. The whole interdependent phantom stage of the

capitalist system has an extremely limited life before it collapses into

chaos.

karlnorth | The Interdependence. Economic

activity at phantom carrying capacity depletes resources at a rate that

causes rising resource costs and decreasing profit margins in the

production of real wealth. The investor class therefore turns

increasingly to the production of credit as a source of profits. Credit

unsupported by the production of real wealth is stealing from the

future: it is phantom wealth. It also creates inflation, which is

stealing from the purchasing power of income in the present. Protected

from the masses by the illusion of democracy, government facilitates the

unlimited production of credit and the continued overshoot of real

carrying capacity. This causes inflation and permanently rising costs of

raw materials. To divert public attention from the resultant declining

living standard of the laboring classes, government dispenses rigged

statistics and fake news of continued growth to project the illusion of

economic health. The whole interdependent phantom stage of the

capitalist system has an extremely limited life before it collapses into

chaos.

By

CNu

at

May 15, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Peak Capitalism

Tuesday, May 14, 2013

what does your state's highest paid employee do?

- Coaches don't generate revenue on their own; you could make the exact same case for the student-athletes who actually play the game and score the points and fracture their legs.

- It can be tough to attribute this revenue directly to the performance of the head coach. In 2011-2012, Mack Brown was paid $5 million to lead a mediocre 8-5 Texas team to the Holiday Bowl. The team still generated $103.8 million in revenue, the most in college football. You don't have to pay someone $5 million to make college football profitable in Texas.

- This revenue rarely makes its way back to the general funds of these universities. Looking at data from 2011-2012, athletic departments at 99 major schools lost an average of $5 million once you take out revenue generated from "student fees" and "university subsidies." If you take out "contributions and donations"—some of which might have gone to the universities had they not been lavished on the athletic departments—this drops to an average loss of $17 million, with just one school (Army) in the black. All this football/basketball revenue is sucked up by coach and AD salaries, by administrative and facility costs, and by the athletic department's non-revenue generating sports; it's not like it's going to microscopes and Bunsen burners

By

CNu

at

May 14, 2013

1 comments

![]()

Labels: American Original , Ass Clownery , What IT DO Shawty...

Chipocalypse Now - I Love The Smell Of Deportations In The Morning

sky | Donald Trump has signalled his intention to send troops to Chicago to ramp up the deportation of illegal immigrants - by posting a...

-

theatlantic | The Ku Klux Klan, Ronald Reagan, and, for most of its history, the NRA all worked to control guns. The Founding Fathers...

-

NYTimes | The United States attorney in Manhattan is merging the two units in his office that prosecute terrorism and international narcot...

-

Wired Magazine sez - Biologists on the Verge of Creating New Form of Life ; What most researchers agree on is that the very first functionin...