Wednesday, November 12, 2014

e.o. wilson on bishop dawkins...,

By

CNu

at

November 12, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: ethics , Genetic Omni Determinism GOD , scientific morality

Saturday, November 08, 2014

gene-centrism vs. multi-level selection

By

CNu

at

November 08, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Genetic Omni Determinism GOD , microcosmos , symbiosis , What IT DO Shawty...

Monday, January 07, 2008

Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Sociobiology

Sociobiology is the study of biological (especially evolutionary and ecological) influences on social behavior in humans.

Sociobiology is the study of biological (especially evolutionary and ecological) influences on social behavior in humans.1975. E.O. Wilson. Sociobiology: The New Synthesis.

1976. Richard Dawkins. The Selfish Gene.

Fitness: measured by the number of offspring produced by an individual that survive and reproduce themselves. For humans there is direct fitness--successful mating--and indirect fitness--helping relatives (with whom one shares genes) to reproduce. Inclusive fitness = direct fitness + indirect fitness

* helping relatives: the biological basis for altruism

* reciprocity can also enhace inclusive fitness

E.O. Wilson has changed his mind. Which leads us to the reality of Group Selection and revisions to the prevailing "wisdom" in that area of inquiry.

One-sentence summary: Multilevel selection needs to become the theoretical foundation of sociobiology, despite the widespread rejection of group selection since the 1960s.

The current foundation of sociobiology is based upon the rejection of group selection in the 1960s and the acceptance thereafter of alternative theories to explain the evolution of cooperative and altruistic behaviors. These events need to be reconsidered in the light of subsequent research. Group selection has become both theoretically plausible and empirically well supported. Moreover, the so-called alternative theories include the logic of multilevel selection within their own frameworks. We review the history and conceptual basis of sociobiology to show why a new consensus regarding group selection is needed and how multilevel selection theory can provide a more solid foundation for sociobiology in the future.

Wilson's new paper concludes;

When Rabbi Hillel was asked to explain the Torah in the time that he could stand on one foot, he famously replied “Do not do unto others that which is repugnant to you. Everything else is commentary.” Darwin’s original insight and the developments reviewed in this article enable us to offer the following one-foot summary of sociobiology’s new theoretical foundation: “Selfishness beats altruism within groups. Altruistic groups beat selfish groups. Everything else is commentary.”I read this paper a few weeks ago in the context of the eugenics flap. I've been waiting for a timely opportunity to submit it for your consideration. In the context of the stellar political discourse that bubbled up in the comments yesterday on Obama - I think I've spotted a good juncture at which to inject it. We shall see....,

By

CNu

at

January 07, 2008

0

comments

![]()

Friday, March 30, 2012

what does e.o. wilson mean by "a social conquest of the earth"?

Smithsonianmag | In his new book, The Social Conquest of Earth, E.O. Wilson explains his theory of everything—how hominids evolved, why war is common, how social insects became social, and why ants and bees and humans are so successful. Science writer Carl Zimmer spoke with Wilson.

Smithsonianmag | In his new book, The Social Conquest of Earth, E.O. Wilson explains his theory of everything—how hominids evolved, why war is common, how social insects became social, and why ants and bees and humans are so successful. Science writer Carl Zimmer spoke with Wilson.When you use the phrase “the social conquest of earth” in the title of your book, what do you mean by that? How have social animals conquered the earth?

The most advanced social insects—ants, termites, many species of bees and wasp—make up only about 3 percent of the known species of animals on earth. But on the land they make up in most habitats upwards of 50 percent of the biomass. And of course humans, one of the very few of the largest animals that have reached the social level, has dominated in every respect.

And you see their social behavior as being key to these two kinds of animals having become so dominant?

When you study social insects, as I have, you see directly why eusocial, advanced social issues overall dominate because they will organize groups of individuals in seizing territory, in appropriating food, in defending their nest and generally controlling the parts of the environment for which they’re specialized.

How do you see the process by which you go from asocial species where insects are living as individuals to these incredibly highly organized societies? What do you see as being the progression through natural selection?

It’s actually fairly clear-cut when you take into account what we know about the evolutionary steps leading from completely solitary to eusocial or advanced social behavior. A great many solitary species—let’s say bees, wasps, the primitive cockroach—in the first stage build a nest and care for the young.

In the next stage, the mother or the mated pair stays with the nest and rears the young, defending them and securing food for them. In the next stage, whereas ordinarily the young would disperse upon reaching maturity, now they remain with the mother or the parents. And if that happens, and they work together as a group, then you have the advanced stage of social behavior.

A lot of scientists see social behavior as being partly the product of what’s called “inclusive fitness,” the effect that genes have not just in terms of an individual animal’s number of offspring but how many offspring their relatives may have. You’ve argued that inclusive fitness is not necessary and that you can focus on natural selection on individuals and on what you call “group selection” to explain how these social animals, like the social insects or humans, evolve their behavior. What do you mean when you use the term group selection?

As you might know, group selection became almost taboo in discussions on social behavior. But it comes back forcefully in the new theory developing about the origin of advanced social behavior.

The way I define it, group selection operates on the fitness, or lack thereof, of the social interactions in the group. In other words, it’s not simply group versus group in that sense but what actions individuals take that affect the group. And that would of course be communication, division of labor and the ability to read others’ intentions, which leads to cooperation.

When it’s an advantage to communicate or cooperate, those genes that promote it are going to be favored in that group if the group is competing with other groups. It gives them superiority over other groups and the selection proceeds at the group level, even as it continues to proceed at the individual level.

By

CNu

at

March 30, 2012

21

comments

![]()

Labels: What IT DO Shawty...

kin and kind: a fight about the genetics of altruism

New Yorker | Charles Darwin regarded the problem of altruism as a potentially fatal challenge to his theory of natural selection. After all, if life were such a cruel “struggle for existence,” then how could a selfless individual ever live long enough to reproduce? Why would natural selection favor a behavior that made us less likely to survive? And yet, as Darwin knew, altruism is everywhere, a stubborn anomaly of nature. For a century after Darwin, altruism remained a paradox.

New Yorker | Charles Darwin regarded the problem of altruism as a potentially fatal challenge to his theory of natural selection. After all, if life were such a cruel “struggle for existence,” then how could a selfless individual ever live long enough to reproduce? Why would natural selection favor a behavior that made us less likely to survive? And yet, as Darwin knew, altruism is everywhere, a stubborn anomaly of nature. For a century after Darwin, altruism remained a paradox.The first glimmers of a solution arrived in the nineteen-fifties. According to legend, the biologist J. B. S. Haldane was asked how far he would go to save the life of another person. Haldane thought for a moment, and then started scribbling numbers on the back of a napkin. “I would jump into a river to save two brothers, but not one,” Haldane said. “Or to save eight cousins but not seven.” His answer summarized a powerful scientific idea. Because individuals share much of their genome with close relatives, a trait will also persist if it leads to the survival of their kin. Haldane never expanded his napkin calculations into a formal mathematical theory. That task fell to William Hamilton. In 1964, he submitted a pair of papers to the Journal of Theoretical Biology. The papers hinged on one simple equation: rB > C. Genes for altruism could evolve if the benefit (B) of an action exceeded the cost (C) to the individual once relatedness (r) was taken into account. Hamilton referred to his model as “inclusive fitness theory.”

At first, Hamilton’s concept of inclusive fitness was entirely ignored. Many biologists were turned off by the math, and few mathematicians were interested in the problems of biology. The following year, however, an ambitious entomologist named E. O. Wilson read the paper. Wilson wanted to understand the altruism at work in ant colonies, and he became convinced that Hamilton had solved the problem. By the late nineteen-seventies, Hamilton’s work was featured prominently in textbooks; his original papers have become some of the most cited in evolutionary biology.

As Wilson realized, the equation allowed naturalists to make sense of animal behavior using genetic models, giving the field a new sense of rigor. In an obituary published after Hamilton’s death, in 2000, the Oxford biologist Richard Dawkins referred to Hamilton as “the most distinguished Darwinian since Darwin.” But now, in an abrupt intellectual shift, Wilson says that his embrace of Hamilton’s equation was a serious scientific mistake. Wilson’s apostasy, which he lays out in a forthcoming book, “The Social Conquest of the Earth,” has set off a scientific furor. The vast majority of his academic colleagues are convinced that he was right the first time, and that his recantation has damaged the field.

The controversy is fuelled by a larger debate about the evolution of altruism. Can true altruism even exist? Is generosity a sustainable trait? Or are living things inherently selfish, our kindness nothing but a mask? This is science with existential stakes. Tells about Wilson’s recent collaboration with Martin Nowak and Corina Tarnita on the paper “The Evolution of Eusociality” and the criticism it received from the scientific community.

By

CNu

at

March 30, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: co-evolution , paradigm

Monday, February 23, 2009

the gene-centric view is just plain wrong...,

It's been a year since my attention focused momentarily on the theoretical repentance of the socio-biologist E.O. Wilson. At the time of that writing, Wilson had a new paper that jarringly and famously concluded;

It's been a year since my attention focused momentarily on the theoretical repentance of the socio-biologist E.O. Wilson. At the time of that writing, Wilson had a new paper that jarringly and famously concluded;When Rabbi Hillel was asked to explain the Torah in the time that he could stand on one foot, he famously replied “Do not do unto others that which is repugnant to you. Everything else is commentary.” Darwin’s original insight and the developments reviewed in this article enable us to offer the following one-foot summary of sociobiology’s new theoretical foundation: “Selfishness beats altruism within groups. Altruistic groups beat selfish groups. Everything else is commentary.”Not recognizing the importance of interactions leads to some unfortunate reasoning. The most obvious of these is Dawkins' idea that genes make phenotypes as "vehicles" to convey them to the next generation. What is truly unfortunate is that this metaphor tended to lead to the idea that genes are all that matters in evolution.

This metaphor to mechanism substitution error encouraged folks to make silly statements like all selection is genetic selection, and to ignore the importance of things like group selection.

In evolutionary biology, group selection refers to the idea that alleles can become fixed or spread in a population because of the benefits they bestow on groups, regardless of the alleles' effect on the fitness of individuals within that group.Finally, it lead to a view of genetic determinism that is at a minimum unfortunate, and in the hands of the politically motivated and magical thinking - is pseudo-scientific, morally repugnant, and dangerous. There is a real intellectual hazard associated with Dawkins one gene one behavior view of the world.

By

CNu

at

February 23, 2009

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Genetic Omni Determinism GOD

Sunday, March 27, 2011

anthropocene

National Geographic | The word "Anthropocene" was coined by Dutch chemist Paul Crutzen about a decade ago. One day Crutzen, who shared a Nobel Prize for discovering the effects of ozone-depleting compounds, was sitting at a scientific conference. The conference chairman kept referring to the Holocene, the epoch that began at the end of the last ice age, 11,500 years ago, and that—officially, at least—continues to this day.

National Geographic | The word "Anthropocene" was coined by Dutch chemist Paul Crutzen about a decade ago. One day Crutzen, who shared a Nobel Prize for discovering the effects of ozone-depleting compounds, was sitting at a scientific conference. The conference chairman kept referring to the Holocene, the epoch that began at the end of the last ice age, 11,500 years ago, and that—officially, at least—continues to this day."'Let's stop it,'" Crutzen recalls blurting out. "'We are no longer in the Holocene. We are in the Anthropocene.' Well, it was quiet in the room for a while." When the group took a coffee break, the Anthropocene was the main topic of conversation. Someone suggested that Crutzen copyright the word.

Way back in the 1870s, an Italian geologist named Antonio Stoppani proposed that people had introduced a new era, which he labeled the anthropozoic. Stoppani's proposal was ignored; other scientists found it unscientific. The Anthropocene, by contrast, struck a chord. Human impacts on the world have become a lot more obvious since Stoppani's day, in part because the size of the population has roughly quadrupled, to nearly seven billion. "The pattern of human population growth in the twentieth century was more bacterial than primate," biologist E. O. Wilson has written. Wilson calculates that human biomass is already a hundred times larger than that of any other large animal species that has ever walked the Earth.

In 2002, when Crutzen wrote up the Anthropocene idea in the journal Nature, the concept was immediately picked up by researchers working in a wide range of disciplines. Soon it began to appear regularly in the scientific press. "Global Analysis of River Systems: From Earth System Controls to Anthropocene Syndromes" ran the title of one 2003 paper. "Soils and Sediments in the Anthropocene" was the headline of another, published in 2004.

At first most of the scientists using the new geologic term were not geologists. Zalasiewicz, who is one, found the discussions intriguing. "I noticed that Crutzen's term was appearing in the serious literature, without quotation marks and without a sense of irony," he says. In 2007 Zalasiewicz was serving as chairman of the Geological Society of London's Stratigraphy Commission. At a meeting he decided to ask his fellow stratigraphers what they thought of the Anthropocene. Twenty-one of 22 thought the concept had merit.

The group agreed to look at it as a formal problem in geology. Would the Anthropocene satisfy the criteria used for naming a new epoch? In geologic parlance, epochs are relatively short time spans, though they can extend for tens of millions of years. (Periods, such as the Ordovician and the Cretaceous, last much longer, and eras, like the Mesozoic, longer still.) The boundaries between epochs are defined by changes preserved in sedimentary rocks—the emergence of one type of commonly fossilized organism, say, or the disappearance of another.

The rock record of the present doesn't exist yet, of course. So the question was: When it does, will human impacts show up as "stratigraphically significant"? The answer, Zalasiewicz's group decided, is yes—though not necessarily for the reasons you'd expect.

By

CNu

at

March 27, 2011

4

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems

Friday, March 06, 2009

the mirage of conscious evolution

Humans are the most adventitious of creatures—a result of blind evolutionary drift. Yet, with the power of genetic engineering we need no longer be ruled by chance. Humankind—so we are told—can shape its own future. According to E.O. Wilson, conscious control of human evolution is not only possible but inevitable:

Humans are the most adventitious of creatures—a result of blind evolutionary drift. Yet, with the power of genetic engineering we need no longer be ruled by chance. Humankind—so we are told—can shape its own future. According to E.O. Wilson, conscious control of human evolution is not only possible but inevitable:... genetic evolution is about to become conscious and volitional, and usher in a new epoch in the history of life. ...The prospect of this 'volitional evolution'—a species deciding what to do about its own heredity—will present the most profound intellectual and ethical choices humanity has ever faced ... humanity will be positioned godlike to take control of its own ultimate fate. It can, if it chooses, alter not just the anatomy and intelligence of the species but also the emotions and creative drive that compose the very core of human nature.

The author of this passage is the greatest contemporary Darwinian. He has been attacked by biologists and social scientists who believe that the human species is not governed by the same laws as other animals. In that war Wilson is undoubtedly on the side of truth. Yet the prospect of conscious human evolution he invokes is a mirage. The idea of humanity taking charge of its destiny makes sense only if we ascribe consciousness and purpose to the species; but Darwin's discovery was that species are only currents in the drift of genes. The idea that humanity can shape its future assumes that it is exempt from this truth.

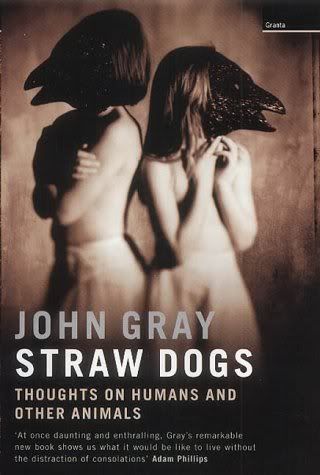

It seems feasible that over the coming century human nature will be scientifically remodelled. If so, it will be done haphazardly, as an upshot of struggles in the murky realm where big business, organised crime, and the hidden parts of government vie for control. If the human species is re-engineered it will not be the result of humanity assuming a godlike control of its destiny. It will be another twist in man's fate. John Gray, Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals

By

CNu

at

March 06, 2009

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Genetic Omni Determinism GOD

Tuesday, December 08, 2009

a beginners guide to evolutionary religious studies

Binghamton | Here are some quick answers to questions that are frequently asked about evolutionary theory in relation to religion and other aspects of human behavior.

Why is the field of evolutionary religious studies so new?

From the very beginning, Darwin and his colleagues were keenly interested in studying all aspects of humanity from an evolutionary perspective, including religion. However, this inquiry led in directions that can be recognized as false in retrospect. Cultural evolution was envisioned as a linear progression from “savagery” to “civilization,” with European societies most advanced. Herbert Spencer and others used evolution to justify a hierarchical society (“Social Darwinism”). Janet Browne’s magnificent 2-volume biography of Darwin and his times (Voyaging and The Power of Place) suggest that these views were inevitable against the background of Victorian culture. Instead of challenging the support that evolutionary theory lent to these views, the theory as a whole became off-limits for many human-related disciplines during most of the 20th century. The controversy surrounding the publication of E.O. Wilson’s Sociobiology in 1975 illustrates the tenor of the times. The modern study of humans from an evolutionary perspective represents a “fresh start” that is based on a much more sophisticated body of theory and knowledge from the biological sciences and bears almost no resemblance to earlier “evolutionary” theories. The field of evolutionary religious studies is part of this broader trend.

How can something as cultural as religion be studied from an evolutionary perspective?

It is typical to portray terms such as “culture” and “learning” as alternatives to terms such as “evolution” and “biology.” According to this formulation, evolutionary theory can explain other species and certain aspects of humans, such as our desire to eat and mate, but not other aspects, such as our rich cultural diversity. This formulation makes little sense from a modern evolutionary perspective. Culture and learning are manifestly important in our species, but they need to be understood from an evolutionary perspective rather than being regarded as an alternative. The capacities for learning and culture require an elaborate architecture that evolved by genetic evolution. Moreover, learning and cultural change can be regarded as fast-paced evolutionary processes in their own right. The bottom line is that evolutionary theory provides a framework for understanding cultural diversity in addition to biological diversity.

If cultural evolution refers to any kind of cultural change, doesn’t it explain nothing by explaining everything?

Consider an analogy with genetic evolution, which is defined as any kind of genetic change, whether by mutation, selection, drift, linkage disequilibrium, and so on. It is important for the definition to include everything to provide a complete accounting system for genetic change. The definition is not empty because specific categories of change are determined on a case-by-case. Thus, we might decide that guppy spots (and their associated genes) evolve primarily by selection, that mitochondrial genes evolve primarily by drift, and so on. Similarly, it is important for the definition of cultural evolution to be all-inclusive to provide a complete accounting system. What saves it from being empty is a number of meaningful sub-categories that can be determined on a case-by-case basis.

What is the relationship between evolutionary theory and other theoretical perspectives, such as Marxism, rational choice theory, or functionalism?

Most scholars and scientists who study religion are not young-earth creationists. They expect religion to be natural phenomenon that can be explained without invoking supernatural agents. They fully accept the theory of evolution, including humans as a product of evolution. Thus, they implicitly assume that their particular theoretical framework is consistent with evolutionary theory, without requiring much knowledge about evolutionary theory. For example, rational choice theory assumes that human behavior can be explained in terms of individual utility maximization. When pressed for an explanation, a rational choice theorist would presumably say that utility maximization evolved as a genetic or cultural adaptation—those who failed to maximize their utilities were not among our ancestors. In this fashion, when the axioms of any given naturalistic perspective are questioned, they involve assumptions about evolution. Unsurprisingly (at least in retrospect) these assumptions can be improved by a sophisticated knowledge of current evolutionary theory. In this fashion, other theoretical perspectives become integrated into evolutionary theory rather than providing an alternative. Virtually all naturalistic theories of religion that were developed without using the E-word can be given a formulation within evolutionary theory, enabling them to be compared with each other more productively than before.

By

CNu

at

December 08, 2009

0

comments

![]()

Labels: The Straight and Narrow

Thursday, January 16, 2014

toward a cross-species understanding of empathy

By

CNu

at

January 16, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: as above-so below

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

e.o.wilson; what is art?

Other artifacts have been found that can plausibly be interpreted as musical instruments. They include thin flint blades that, when hung together and struck, produce pleasant sounds like those from wind chimes. Further, although perhaps just a coincidence, the sections of walls on which cave paintings were made tend to emit arresting echoes of sound in their vicinity.

Was music Darwinian? Did it have survival value for the Paleolithic tribes that practiced it? Examining the customs of contemporary hunter-gatherer cultures from around the world, one can hardly come to any other conclusion. Songs, usually accompanied by dances, are all but universal. And because Australian aboriginals have been isolated since the arrival of their forebears about 45,000 years ago, and their songs and dances are similar in genre to those of other hunter-gatherer cultures, it is reasonable to suppose that they resemble the ones practiced by their Paleolithic ancestors.

By

CNu

at

April 25, 2012

4

comments

![]()

Labels: Ass Clownery

Wednesday, January 14, 2009

magical false positives...,

By

CNu

at

January 14, 2009

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, July 06, 2010

bones and feathers and wishful thinking...?

Guardian | In this published version of the Terry lectures, delivered at Yale University last year, the novelist Marilynne Robinson argues that positivism, the belief that science is the only reliable means to truth, has adopted a "systematically reductionist" view of human nature. Since Huxley, for example, Darwinians have found altruism problematic, as evolution would necessarily select against benevolence to another at cost to oneself. Altruism can only occur because of the "selfishness" of a gene. Thus for EO Wilson, a "soft-core altruist" expects reciprocation from either society or family; his byzantine calculations are characterised by "lying, pretence and deceit, including self-deceit, because the actor is more convincing who believes that his performance is real". Every apparently compassionate action is, therefore, simply a matter of quid pro quo.

Guardian | In this published version of the Terry lectures, delivered at Yale University last year, the novelist Marilynne Robinson argues that positivism, the belief that science is the only reliable means to truth, has adopted a "systematically reductionist" view of human nature. Since Huxley, for example, Darwinians have found altruism problematic, as evolution would necessarily select against benevolence to another at cost to oneself. Altruism can only occur because of the "selfishness" of a gene. Thus for EO Wilson, a "soft-core altruist" expects reciprocation from either society or family; his byzantine calculations are characterised by "lying, pretence and deceit, including self-deceit, because the actor is more convincing who believes that his performance is real". Every apparently compassionate action is, therefore, simply a matter of quid pro quo.In the same way, because it transfers useful information to somebody else and requires an expenditure of time and energy, language seems essentially altruistic. But, says the evolutionary biologist Geoffrey Miller, "evolution cannot favour altruistic information-sharing", so the complexities of language probably evolved simply for verbal courtship, "providing a sexual payoff for eloquent speaking by the male and female".

"Oh, to have been a fly on the wall!" Robinson comments wryly, when our "proto-verbal ancestors found mates through eloquent proto-speech". In the same way, art may appear to be "an exploration of experience, of the possibilities of communication, and of the extraordinary collaboration of eye and hand," but according to some neo-Darwinians, it too is simply a means of attracting sexual partners. "Leonardo and Rembrandt may have thought they were competent inquirers in their own right, but we moderns know better."

This disdainful "hermeneutics of condescension" cannot function outside of a narrow definition of relative data. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the positivist critique of religion. Daniel Dennett, for example, defines religion as "social systems whose participants avow belief in a supernatural agent or agents whose approval is to be sought". He deliberately avoids the contemplative side of faith explored by William James, as if, Robinson says, "religion were only what could be observed using the methods of anthropology or of sociology, without reference to the deeply pensive solitudes that bring individuals into congregations". Bypassing Donne, Bach, the Sufi poets and Socrates, Dennett, Dawkins and others are free to reduce the multifarious religious experience of humanity "to a matter of bones and feathers and wishful thinking, a matter of rituals and social bonding and false etiologies and the fear of death".

Robinson takes the science-versus-religion debate a stage further. More significant than this jejune attack on faith, she argues, is the disturbing fact that "the mind, as felt experience, has been excluded from important fields of modern thought" and as a result "our conception of humanity has shrunk". Robinson's argument is prophetic, profound, eloquent, succinct, powerful and timely. It is not an easy read, but one of her objectives is to help readers appreciate the complexity of these issues. To adopt such a "closed ontology", she insists, is to ignore "the beauty and the strangeness" of the individual mind as it exists in time. Subjectivity "is the ancient haunt of piety and reverence and long, long thoughts. And the literatures that would dispel such things refuse to acknowledge subjectivity, perhaps because inability has evolved into principle and method."

By

CNu

at

July 06, 2010

0

comments

![]()

Labels: as above-so below

Chipocalypse Now - I Love The Smell Of Deportations In The Morning

sky | Donald Trump has signalled his intention to send troops to Chicago to ramp up the deportation of illegal immigrants - by posting a...

-

theatlantic | The Ku Klux Klan, Ronald Reagan, and, for most of its history, the NRA all worked to control guns. The Founding Fathers...

-

NYTimes | The United States attorney in Manhattan is merging the two units in his office that prosecute terrorism and international narcot...

-

Wired Magazine sez - Biologists on the Verge of Creating New Form of Life ; What most researchers agree on is that the very first functionin...