Tuesday, July 15, 2014

self-segregation on the basis of core western values

By

CNu

at

July 15, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: cultural darwinism , Peak Capitalism , The Hardline

friendship segregation by genetic compatibility

By

CNu

at

July 15, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Monday, July 14, 2014

metropolitan segregation by education

By

CNu

at

July 14, 2014

32

comments

![]()

Labels: cultural darwinism , galt's gulch , What IT DO Shawty...

corporate segregation by inversion

By

CNu

at

July 14, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: cultural darwinism , galt's gulch , global system of 1% supremacy

economic segregation by stupidity

By

CNu

at

July 14, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Ass Clownery , Collapse Crime , cultural darwinism

Sunday, July 13, 2014

to understand a thing is to know whether or not to waste your breath in futile conversation with it...,

pbs | On Making Sen$e this week, we’ve been publishing Paul Solman’s never-aired conversation with economic historian Gregory Clark about his 2007 book,“A Farewell to Alms.” In Friday’s installment, we get to the really controversial part: that genetics may explain why some societies, specifically industrial England, grew economically.

But, first, a recap of the journey Clark has taken us on this week. In the beginning of human history, population was limited by the limited resources to keep humans alive (this is the “Malthusian” economic view developed by Thomas Malthus.) And so with more violence (not to mention fewer working hours), hunter-gatherer society, Clark argued in part one of this interview, was easier than life in pre-industrial England, where material life was harder.

But that changed with the Industrial Revolution. Suddenly, the West got rich. One of the world’s intellectual puzzles has been, why and how did England break out of that Malthusian trap? In part two, Clark explained how human nature – indeed our very patience for gratification – changed as we moved from hunter-gatherer society to 1800.

England wasn’t the site of fast economic growth, as the economics literature has long preached, because of the existence of political and market institutions. No, Clark said in part three, England’s economic growth stemmed from the “survival of the richest;” those who personalities were best suited for capitalism thrived.

And now for the truly controversial part. Those traits, like being materially-driven and being able to wait for gratification (think of the marshmallow test), vary by class, and even if Clark believed (and hoped) that cultural transmission explains the class variance, he saw nothing to rule out a genetic explanation.

Paul Solman: The reason that the New York Times science section did this whole big story on you, even before this book came out, surely is because of the genetic part of this explanation, yes? Is that fair?

Greg Clark: Absolutely. And it is a fascinating possibility. Most of the assumption has been that basically human nature was completed in the hunter-gatherer era, that there wasn’t enough time between the hunter-gatherer era and the modern world for any further significant changes in people’s basic nature.

I think the data from somewhere like England, and this is just suggestive, and also the information about these fairly fundamental changes in features like people’s patience, or the amount of work that people do, at least raises the possibility that there was a further change in people, booting the Neolithic revolution and the onset of the Industrial Revolution.

By

CNu

at

July 13, 2014

12

comments

![]()

Labels: essence , global system of 1% supremacy , What IT DO Shawty...

the detroit experiment: evolve or die...,

Species develop characteristics which give them competitive advantage. Dinosaurs get big so no predators can eat them up. Saber tooth tigers develop monster jaws so they can chomp on mastadons and other large prey.

But the problem is that species continue to develop these characteristics beyond the point of maximum advantage. Dinosaurs get so big that they need to get a second brain in their midsection to manage their bodies and they die of anatomical schizophrenia. Saber-tooth tiger become such efficient killers of large prey that they begin to wipe them out, and their hypertrophied jaws are badly adapted to killing smaller prey, so they die of starvation. And humans have developed overly large brains and are in the process of thinking themselves to death.

By

CNu

at

July 13, 2014

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Collapse Casualties , essence , What IT DO Shawty...

to understand the machine is to be able to control and exploit the machine...,

By

CNu

at

July 13, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: cognitive infiltration , essence , Livestock Management

Saturday, July 12, 2014

european neuroscientists boycotting the european version of BRAIN?

..we wish to express the view that the HBP [Human Brain Project] is not on course and that the European Commission must take a very careful look at both the science and the management of the HBP before it is renewed. We strongly question whether the goals and implementation of the HBP are adequate to form the nucleus of the collaborative effort in Europe that will further our understanding of the brain.

It seems that it will take decades more for the neuroscience community to mature to the level of other disciplines. This is such an exciting direction that can bring everyone together to take on this grand challenge. Just so sad that it gets torn apart by scientists that don’t want to understand, that believe second-hand rumors and just want money for their next experiment. For the first time in my career as a neuroscientist, I lose hope of neuroscience ever answering any real questions about how the brain works and its many diseases.

A large group (now more than 250) neuroscientists in Europe are trying to send a wake up call to the European Commission to say that the Human Brain Project is not an effective vehicle to form the hub of European neuroscience. Unlike the U.S. Brain initiative, the HBP is a narrowly focused information computing technology effort that, contrary to how it was sold, does not have a realistic plan for understanding brain function. We want the public to know that neuroscience research is not represented by the HBP. We hope that the open message to the EC can help to initiate a dialogue and find a better solution.

By

CNu

at

July 12, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: micro-insurgencies , neuromancy , What Now?

attention as an effect not a cause: (the basic function you cats typically conflate with consciousness)

- •Current models of attention are based on the premise of limited sensory resources.

- •We propose that attention arises as a byproduct of value-based decision making.

- •Decision making requires estimating the current state of the animal and environment.

- •Filter-like properties of attention arise from weighted inputs to the current state.

- •The brain mechanisms involve a subcortical circuit motif that predates the neocortex.

By

CNu

at

July 12, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: essence , What IT DO Shawty...

neurological evidence for chaos in the nervous system is growing...,

By

CNu

at

July 12, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: neuromancy , randomization , What IT DO Shawty...

Friday, July 11, 2014

Thursday, July 10, 2014

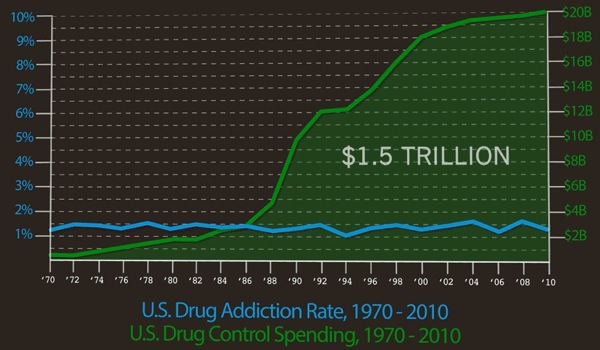

the wages of dehumanizing drug "offenders"...,

Chong was a 24-year-old engineering student when he was caught up in the drug sweep by a DEA task force two years ago.

On the morning of April 21, 2012, Chong was detained with six other suspects and transported to the DEA field office, where agents determined that he was not involved in the ecstasy ring that was under investigation.

A self-confessed pot smoker, Chong told investigators he had gone to the University City apartment that Friday night to celebrate April 20 — an important day for marijuana users — and spent the night.

After being interviewed at the DEA field office Saturday, agents told Chong he would be released without charges and driven home soon.

But agents forgot about him and Chong spent the next four and half days inside the five-by-10-foot cell without food, water or a toilet. He said his screams for help went unanswered.

Chong was discovered near death on Wednesday afternoon. Agents called 911 and he was rushed to a hospital. Chong spent four days in the hospital for multiple conditions but has since recovered.

Four different federal drug agents saw or heard Daniel Chong during the five days he was handcuffed in a holding cell without food or water after a 2012 narcotics sweep, a U.S. Department of Justice report released on Tuesday found.

The agents did nothing because they assumed someone else was responsible for the detainee, and because there was no training for agents on how to track and monitor wards at the Kearny Mesa detention center, the report found.

By

CNu

at

July 10, 2014

23

comments

![]()

Labels: civil war , narcoterror , What IT DO Shawty...

taxpayers fund political propaganda training for the narcopopo

By

CNu

at

July 10, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Wednesday, July 09, 2014

Tuesday, July 08, 2014

through the anthropocene looking glass...,

By

CNu

at

July 08, 2014

21

comments

![]()

Labels: macrobiology , tactical evolution , What Now?

Monday, July 07, 2014

information-based fitness and the emergence of criticality in living systems

By

CNu

at

July 07, 2014

14

comments

![]()

Labels: quantum , quorum sensing? , What IT DO Shawty...

legalization has reduced colorado to a lawless dystopian hellscape..., NOT!

By

CNu

at

July 07, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: legalization , weather report

Sunday, July 06, 2014

shrooms provide lucid access to liminal qualia

By

CNu

at

July 06, 2014

16

comments

![]()

Labels: neuromancy

the neurological locus of consciousness?

By

CNu

at

July 06, 2014

13

comments

![]()

Labels: neuromancy

Have You Ever Heard Of An Innocent Person Getting A Pre-emptive Pardon?

December, 2020. Joy Reid: Have you ever heard of somebody getting a preemptive pardon who is an innocent person? Adam Schiff: No. Today Adam...

-

theatlantic | The Ku Klux Klan, Ronald Reagan, and, for most of its history, the NRA all worked to control guns. The Founding Fathers...

-

Video - John Marco Allegro in an interview with Van Kooten & De Bie. TSMATC | Describing the growth of the mushroom ( boletos), P...

-

dailybeast | Of all the problems in America today, none is both as obvious and as overlooked as the colossal human catastrophe that is our...