From theBible moralisée - anything odd about the motif inside the geometer's compass? Fist tap Dale.

Sunday, June 03, 2012

what have we here?

By

CNu

at

June 03, 2012

2

comments

![]()

Labels: History's Mysteries

Saturday, June 02, 2012

goodbye faculty

Education is the means of propagating knowledge from one generation to the next. Education has grown exponentially, both in terms of its own food-powered/make-work employment base, and, in terms of the numbers of these humans receiving it. Sadly, for the most part, education methods and results have not improved.

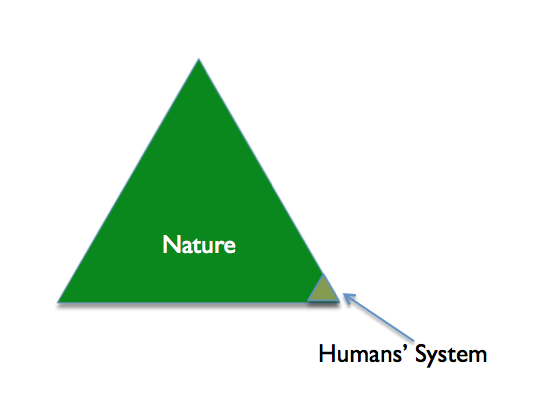

Education is the means of propagating knowledge from one generation to the next. Education has grown exponentially, both in terms of its own food-powered/make-work employment base, and, in terms of the numbers of these humans receiving it. Sadly, for the most part, education methods and results have not improved.Education is commonly regarded as a good. It is seen as being a means of ensuring the continuing development of society. Ironically, one of its continuing deficiencies is that as currently configured, it fosters the fallacious belief that society can continue to grow without paying ecological costs.

That hallucination is coming to an end, even though few currently understand that fact. Various forms of human growth - population, economies, affluence, information and misunderstanding are unsustainable and coming to an end. There will continue to be a place for various forms of education as society seeks to power down with as little pain as possible.

Knowledge of science and engineering principles will make primary contributions given increasing demand for frugal operation and maintenance of the vast infrastructure of civilization. However, economics based on unsound and fallacious principles must soon die.

Relearning how to use only natural forces to produce and distribute food will take curricular center stage. Research will cease to advance the frontiers of knowledge about extraneous issues as it seeks to make best use of what natural capital is still available. The redirection of education is bound to head the agenda as society slowly wakes up to what civilization has done wrong.

prosperouswaydown | Goodbye faculty, hello neoliberal MOOCs. I read a NY Times article last week and was clued into a recent ‘innovation’ in education which may soon be sweeping the globe. Massively Open Online Courses or MOOCs are being produced and promoted by some of the most prestigious universities in the world, such as a just announced MIT-Harvard ‘nonprofit’ partnership, and another with Stanford, Princeton, UPenn, and Michigan. MOOC courses include video lesson segments, embedded quizzes, immediate feedback and student-paced learning, and most so far have been produced in the areas of engineering, computers, software, etc, but courses in all fields are clearly coming. Most of the article is techy and upbeat, but they let this quote slip in. George Siemens, a MOOC pioneer ominously said, “But if I were president of a mid-tier university, I would be looking over my shoulder very nervously right now, because if a leading university offers a free circuits course, it becomes a real question whether other universities need to develop a circuits course.” Get it? This is the end of universities as we know them. A few top universities produce coursework for the world and there’s no need for any of the rest of you out there. Still, the reporter tries to keep it positive and ends with this quote, “What’s still missing is an online platform that gives faculty the capacity to customize the content of their own highly interactive courses.” That’s right, we’ll still need you to ‘customize’ the MOOC course for your classrooms.

So I started to search for articles on MOOCs. It’s all tech hype and whiz-bang. I could find nary a discouraging word. And I certainly could not find what I was really looking for, which is the corporate strategy behind all of this. Why are the big boys interested? I have some of my own ideas that I will try to relate and that refer particularly to issues of peak and descent.

By

CNu

at

June 02, 2012

16

comments

![]()

Labels: change , Collapse Casualties

markets and morals?

Or that Project Prevention, a charity, pays women with drug or alcohol addictions $300 cash to get sterilized or undertake long-term contraception? Some 4,100 women have accepted this offer.

Michael Sandel, the Harvard political theorist, cites those examples in “What Money Can’t Buy,” his important and thoughtful new book. He argues that in recent years we have been slipping without much reflection into relying upon markets in ways that undermine the fairness of our society.

That’s one of the underlying battles this campaign year. Many Republicans, Mitt Romney included, have a deep faith in the ability of laissez-faire markets to create optimal solutions.

There’s something to that faith because markets, indeed, tend to be efficient. Pollution taxes are widely accepted as often preferable than rigid regulations on pollutants. It may also make sense to sell advertising on the sides of public buses, perhaps even to sell naming rights to subway stations.

Still, how far do we want to go down this path?

Is it right that prisoners in Santa Ana, Calif., can pay $90 per night for an upgrade to a cleaner, nicer jail cell?

Should the United States really sell immigration visas? A $500,000 investment will buy foreigners the right to immigrate.

hould Massachusetts have gone ahead with a proposal to sell naming rights to its state parks? The Boston Globe wondered in 2003 whether Walden Pond might become Wal-Mart Pond.

Should strapped towns accept virtually free police cars that come laden with advertising on the sides? Such a deal was negotiated and then ultimately collapsed, but at least one town does sell advertising on its police cars.

“The marketization of everything means that people of affluence and people of modest means lead increasingly separate lives,” Sandel writes. “We live and work and shop and play in different places. Our children go to different schools. You might call it the skyboxification of American life. It’s not good for democracy, nor is it a satisfying way to live.”

“Do we want a society where everything is up for sale? Or are there certain moral and civic goods that markets do not honor and money cannot buy?”

By

CNu

at

June 02, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Collapse Casualties , reality casualties

significant UK light crude refinery to shutdown this week...,

Guardian | The UK's financially strapped Coryton refinery will run out of crude oil and shut down in phases beginning by the middle of next week, its joint administrator has said.

The prospects of finding a buyer for Coryton look increasingly remote, warned Steven Pearson of PricewaterhouseCoopers.

The refinery was one of several owned by Petroplus, Europe's largest independent refiner, before it declared insolvency.

Pearson said: "The plant will run out of crude oil to refine, and there are no ships on the way," adding that staff would remain for the time being to help shut the plant safely. "We will not announce any immediate redundancies – we'll have more detail in a week's time."

The plant employs 900 people including contractors.

By

CNu

at

June 02, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems , Irreplaceable Natural Material Resources

Friday, June 01, 2012

capitol as power...,

This breakdown is no accident. Every mode of power evolves together with its dominant theories and ideologies. In capitalism, these theories and ideologies originally belonged to the study of political economy – the first mechanical science of society. But the capitalist mode of power kept changing, and as the power underpinnings of capital became increasingly visible, the science of political economy disintegrated. By the late nineteenth century, with dominant capital having taken command, political economy was bifurcated into two distinct spheres: economics and politics. And in the twentieth century, when the power logic of capital had already penetrated every corner of society, the remnants of political economy were further fractured into mutually distinct social sciences. Nowadays, capital reigns supreme – yet social scientists have been left with no coherent framework to account for it.

The theory of Capital as Power offers a unified alternative to this fracture. It argues that capital is not a narrow economic entity, but a symbolic quantification of power. Capital has little to do with utility or abstract labor, and it extends far beyond machines and production lines. Most broadly, it represents the organized power of dominant capital groups to reshape – or creorder – their society.

This view leads to a different cosmology of capitalism. It offers a new theoretical framework for capital based on the twin notions of dominant capital and differential accumulation, a new conception of the state of capital and a new history of the capitalist mode of power. It also introduces new empirical research methods – including new categories; new ways of thinking about, relating and presenting data; new estimates and measurements; and, finally, the beginning of a new, disaggregate accounting that reveals the conflictual dynamics of society.

By

CNu

at

June 01, 2012

4

comments

![]()

Labels: The Hardline , truth

Thursday, May 31, 2012

how bad is it?

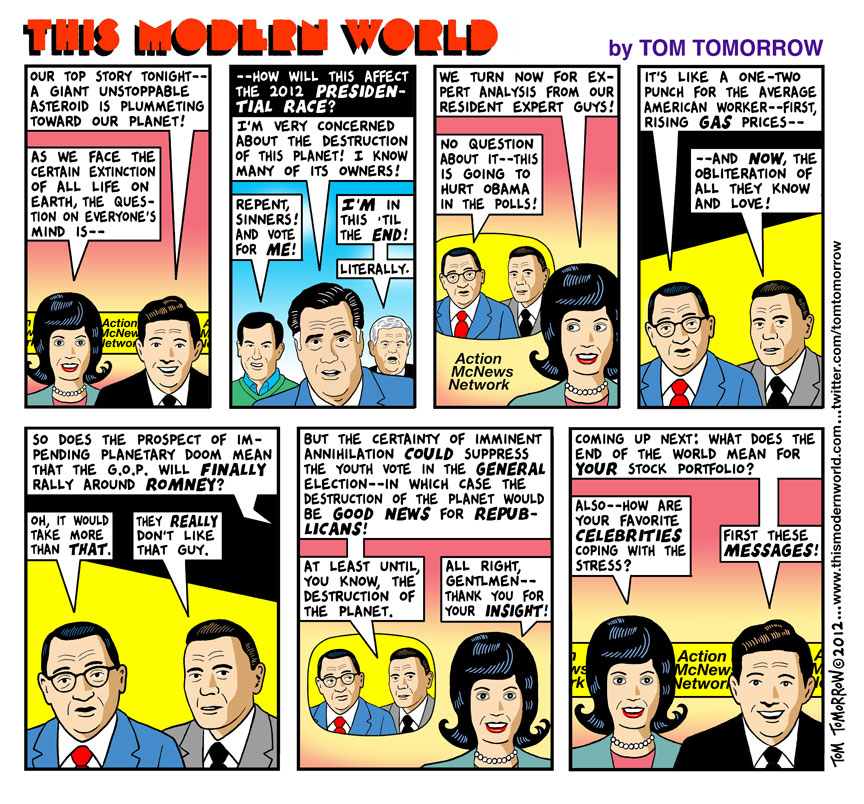

the new inquiry | Pretty bad. Here is a sample of factlets from surveys and studies conducted in the past twenty years. Seventy percent of Americans believe in the existence of angels. Fifty percent believe that the earth has been visited by UFOs; in another poll, 70 percent believed that the U.S. government is covering up the presence of space aliens on earth. Forty percent did not know whom the U.S. fought in World War II. Forty percent could not locate Japan on a world map. Fifteen percent could not locate the United States on a world map. Sixty percent of Americans have not read a book since leaving school. Only 6 percent now read even one book a year. According to a very familiar statistic that nonetheless cannot be repeated too often, the average American’s day includes six minutes playing sports, five minutes reading books, one minute making music, 30 seconds attending a play or concert, 25 seconds making or viewing art, and four hours watching television.

the new inquiry | Pretty bad. Here is a sample of factlets from surveys and studies conducted in the past twenty years. Seventy percent of Americans believe in the existence of angels. Fifty percent believe that the earth has been visited by UFOs; in another poll, 70 percent believed that the U.S. government is covering up the presence of space aliens on earth. Forty percent did not know whom the U.S. fought in World War II. Forty percent could not locate Japan on a world map. Fifteen percent could not locate the United States on a world map. Sixty percent of Americans have not read a book since leaving school. Only 6 percent now read even one book a year. According to a very familiar statistic that nonetheless cannot be repeated too often, the average American’s day includes six minutes playing sports, five minutes reading books, one minute making music, 30 seconds attending a play or concert, 25 seconds making or viewing art, and four hours watching television.

Among high-school seniors surveyed in the late 1990s, 50 percent had not heard of the Cold War. Sixty percent could not say how the United States came into existence. Fifty percent did not know in which century the Civil War occurred. Sixty percent could name each of the Three Stooges but not the three branches of the U.S. government. Sixty percent could not comprehend an editorial in a national or local newspaper.

Intellectual distinction isn’t everything, it’s true. But things are amiss in other areas as well: sociability and trust, for example. “During the last third of the twentieth century,” according to Robert Putnam in Bowling Alone, “all forms of social capital fell off precipitously.” Tens of thousands of community groups – church social and charitable groups, union halls, civic clubs, bridge clubs, and yes, bowling leagues — disappeared; by Putnam’s estimate, one-third of our social infrastructure vanished in these years. Frequency of having friends to dinner dropped by 45 percent; card parties declined 50 percent; Americans’ declared readiness to make new friends declined by 30 percent. Belief that most other people could be trusted dropped from 77 percent to 37 percent. Over a five-year period in the 1990s, reported incidents of aggressive driving rose by 50 percent — admittedly an odd, but probably not an insignificant, indicator of declining social capital.

Still, even if American education is spotty and the social fabric is fraying, the fact that the U.S. is the world’s richest nation must surely make a great difference to our quality of life? Alas, no. As every literate person knows, economic inequality in the United States is off the charts – at third-world levels. The results were recently summarized by James Speth in Orion magazine. Of the 20 advanced democracies in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the U.S. has the highest poverty rate, for both adults and children; the lowest rate of social mobility; the lowest score on UN indexes of child welfare and gender inequality; the highest ratio of health care expenditure to GDP, combined with the lowest life expectancy and the highest rates of infant mortality, mental illness, obesity, inability to afford health care, and personal bankruptcy resulting from medical expenses; the highest homicide rate; and the highest incarceration rate. Nor are the baneful effects of America’s social and economic order confined within our borders; among OECD nations the U.S. also has the highest carbon dioxide emissions, the highest per capita water consumption, the next-to-largest ecological footprint, the next-to-lowest score on the Yale Environmental Performance Index, the highest (by a colossal margin) per capita rate of military spending and arms sales, and the next-to-lowest rate of per capita spending on international development and humanitarian assistance.

By

CNu

at

May 31, 2012

2

comments

![]()

Labels: American Original , truth

SoCiaL MeDiA CoNFiDeNTiaL...

By

CNu

at

May 31, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: American Original , hustle-hard

lagarde to greeks: it's payback time!

In an uncompromising interview with the Guardian, Lagarde insists it is payback time for Greece and makes it clear that the IMF has no intention of softening the terms of the country's austerity package.

Using some of the bluntest language of the two-and-a-half-year debt crisis, she says Greek parents have to take responsibility if their children are being affected by spending cuts. "Parents have to pay their tax," she says.

Greece, which has seen its economy shrink by a fifth since the recession began, has been told to cut wages, pensions and public spending in return for financial help from the IMF, the European Union and the European Central Bank.

Asked whether she is able to block out of her mind the mothers unable to get access to midwives or patients unable to obtain life-saving drugs, Lagarde replies: "I think more of the little kids from a school in a little village in Niger who get teaching two hours a day, sharing one chair for three of them, and who are very keen to get an education. I have them in my mind all the time. Because I think they need even more help than the people in Athens."

Lagarde, predicting that the debt crisis has yet to run its course, adds: "Do you know what? As far as Athens is concerned, I also think about all those people who are trying to escape tax all the time. All these people in Greece who are trying to escape tax." She says she thinks "equally" about Greeks deprived of public services and Greek citizens not paying their tax.

"I think they should also help themselves collectively." Asked how, she replies: "By all paying their tax."

Asked if she is essentially saying to the Greeks and others in Europe that they have had a nice time and it is now payback time, she responds: "That's right."

By

CNu

at

May 31, 2012

4

comments

![]()

Labels: governance , Peak Capitalism

Wednesday, May 30, 2012

how much does washington spend on "defense"?

For those keeping a careful eye out, U.S. drone (and air) bases in the region have been proliferating -- in the Seychelles Islands, in Ethiopia, and at an unidentified site on the Arabian peninsula, among other places. Recently, however, Wired’s Danger Room website reported that an Italian blogger had put the pieces together and offered impressive evidence of a larger war-making effort in the region, involving not only drones but F-15E fighter jets, possibly being used to bomb Yemen. Meanwhile, there are U.S. drone strikes in Yemen almost daily and at least 20 special forces operatives are reportedly now on the ground there, helping direct some of the fighting and even taking casualties.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Africa Command (Africom), set up in 2007, has been gaining clout. In 2011, 100 special operations troops, mainly Green Berets, were moved into Central Africa, officially to aid in the hunting down of Joseph Kony, leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army. Recently, it was reported that a brigade of regular U.S. combat troops will soon be assigned to the command and given training duties throughout the region. Meanwhile, the U.S. has been organizing a proxy war, supported by drone attacks, against al-Shabab rebels in Somalia, using Ugandan, Kenyan, and other African troops as those proxies. And more’s afoot. It’s just that, if you weren’t an obsessive news watcher, you would have next to no way of knowing that any of this was taking place.

War American-style, already long detached from the lives of most Americans, is growing more so: ever more secret, presidential, and beyond the control of, or accountability to, citizens or Congress. In only one way is this not true: we taxpayers still fork over the massive sums that make our perpetual state of war and war state possible. As Chris Hellman and Mattea Kramer of the invaluable National Priorities Project report, the expense of all this is blowing a hole in your wallet and our treasury. To offer but one small example, if someday soon the Pakistani/Afghan border is reopened to U.S. war supplies, you will be paying the Pakistanis $1,500-$1,800 for every truck that crosses it, at an estimated cost of at least $1 million a day (with other "fees" likely). And yet, it’s remarkable how little Americans know about what’s coming out of their pockets when the subject is “national security,” or where exactly it’s all going. Which is why we need Hellman and Kramer (and their new book, A People’s Guide to the Federal Budget) to keep us in the loop. Tom

By

CNu

at

May 30, 2012

5

comments

![]()

Labels: unspeakable

global scarcity: scramble for dwindling natural resources

Michael Klare, a professor of peace and world security studies at Hampshire College in Massachusetts, devotes much of his time these days to thinking about the intensifying competition for increasingly scarce natural resources. His most recent book, The Race for What’s Left: The Global Scramble for the World’s Last Resources, describes how the world economy has entered a period of what he calls “tough” extraction for energy, minerals, and other commodities, meaning that the easy-to-get resources have been exploited and a rapidly growing population is now turning to resources in the planet’s most remote regions — the Arctic, the deep ocean, and war zones like Afghanistan. The exploitation of “tough” resources, such as “fracking” for natural gas in underground shale formations, carries with it far greater environmental risk, Klare says.

In an interview with Yale Environment 360 contributor Diane Toomey, Klare discussed China’s surging appetite for resources, the growing potential for political and military conflict as commodities become more scarce, and the disturbing trend of the planet’s agricultural land being bought by companies and governments seeking to ensure that their people will have enough food in the future. The way to reduce resource conflicts, says Klare, is to find substitute materials and to significantly boost efficiency in a host of realms, most notably energy. Hope for the future, he says, lies with innovative entrepreneurs and, especially, the young. “They all want to be involved in developing solutions,” said Klare, “and they have a lot of optimism and enthusiasm for this.”

Yale Environment 360: You make the point that when it comes to the age-old competition for raw materials, we’re in an unprecedented age. How so?

Michael Klare: I do believe that’s the case. Humans have been struggling to gain control of vital resources since the beginning of time, but I think we’re in a new era because we’re running out of places to go. Humans have constantly moved to new areas, to new continents, when they’ve run out of things in their home territory. But there aren’t any more new continents to go to. We’re going now to the last places left on earth that haven’t been exploited: the Arctic, the deep oceans, the inner jungles in Africa, Afghanistan. There are very few places left that haven’t been fully tapped, so this is humanity’s last chance to exploit the earth, and after this there’s nowhere else to go.

e360: Natural resource extraction has never been a pretty business when it comes to the environment, but you write that now that the era of easy oil, easy gas, easy minerals and other resources is basically over, and what’s left is in deep water, remote or inhospitable climates, or in geological formations that require extraordinary means to get at. So paint me a picture of what extracting these tough resources looks like.

Klare: We’re really going to be using very aggressive means of extraction, so the environmental consequences are going to be proportionally greater. For example, to get oil and natural gas out of shale rock, you can’t just drill

Oil companies want to turn this country back to what it was before environmentalism became an issue.”and expect it to come out. It doesn’t work that way. You have to smash the rock, you have to produce fractures in the rock, and we use a very aggressive technology to do that — hydraulic fracturing — and the water is brought under tremendous pressure and it’s laced with toxic chemicals, and when the water is extracted from these wells it can’t be put back into the environment without risk of poisoning water supplies. So there’s a tremendous problem of storage, of toxic water supplies, and we really haven’t solved that problem.

By

CNu

at

May 30, 2012

1 comments

![]()

Labels: resource war

earnest callenbach: last words to an america in decline

Callenbach once called that book “my bet with the future,” and in publishing terms it would prove a pure winner. To date it has sold nearly a million copies and been translated into many languages. On second look, it proved to be a book not only ahead of its time but (sadly) of ours as well. For me, it was a unique rereading experience, in part because every page of that original edition came off in my hands as I turned it. How appropriate to finish Ecotopia with a loose-leaf pile of paper in a New York City where paper can now be recycled and so returned to the elements.

Callenbach would have appreciated that. After all, his novel, about how Washington, Oregon, and Northern California seceded from the union in 1979 in the midst of a terrible economic crisis, creating an environmentally sound, stable-state, eco-sustainable country, hasn’t stumbled at all. It’s we who have stumbled. His vision of a land that banned the internal combustion engine and the car culture that went with it, turned in oil for solar power (and other inventive forms of alternative energy), recycled everything, grew its food locally and cleanly, and in the process created clean skies, rivers, and forests (as well as a host of new relationships, political, social, and sexual) remains amazingly lively, and somehow almost imaginable -- an approximation, that is, of the country we don’t have but should or even could have.

Callenbach’s imagination was prodigious. Back in 1975, he conjured up something like C-SPAN and something like the cell phone, among many ingenious inventions on the page. Ecotopia remains a thoroughly winning book and a remarkable feat of the imagination, even if, in the present American context, the author also dreamed of certain things that do now seem painfully utopian, like a society with relative income equality.

“Chick” -- as he was known, thanks, it turns out, to the chickens his father raised in Appalachian central Pennsylvania in his childhood -- was, like me, an editor all his life. He founded the prestigious magazine Film Quarterly in 1958. In the late 1970s, I worked with him and his wife, Christine Leefeldt, on a book of theirs, The Art of Friendship. He also wrote a successor volume to Ecotopia (even if billed as a prequel), Ecotopia Emerging. And as he points out in his last piece, today’s TomDispatch post, he, too, has now been recycled. He died of cancer on April 16th at the age of 83.

Just days later, his long-time literary agent Richard Kahlenberg wrote me that Chick had left a final document on his computer, something he had been preparing in the months before he knew he would die, and asked if TomDispatch would run it. Indeed, we would. It’s not often that you hear words almost literally from beyond the grave -- and eloquent ones at that, calling on all Ecotopians, converted or prospective, to consider the dark times ahead. Losing Chick’s voice and his presence is saddening. His words remain, however, as do his books, as does the possibility of some version of the better world he once imagined for us all. Tom

By

CNu

at

May 30, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: weather report

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

video games and porn...,

Increasingly, researchers say yes, as young men become hooked on arousal, sacrificing their schoolwork and relationships in the pursuit of getting a tech-based buzz.

Every compulsive gambler, alcoholic or drug addict will tell you that they want increasingly more of a game or drink or drug in order to get the same quality of buzz.

Video game and porn addictions are different. They are "arousal addictions," where the attraction is in the novelty, the variety or the surprise factor of the content. Sameness is soon habituated; newness heightens excitement. In traditional drug arousal, conversely, addicts want more of the same cocaine or heroin or favorite food.

The consequences could be dramatic: The excessive use of video games and online porn in pursuit of the next thing is creating a generation of risk-averse guys who are unable (and unwilling) to navigate the complexities and risks inherent to real-life relationships, school and employment.

Stories about this degeneration are rampant: In 2005, Seungseob Lee, a South Korean man, went into cardiac arrest after playing "StarCraft" for nearly 50 continuous hours. In 2009, MTV's "True Life" highlighted the story of a man named Adam whose wife kicked him out of their home -- they have four kids together -- because he couldn't stop watching porn.

Norwegian mass murder suspect Anders Behring Breivik reported during his trial that he prepared his mind and body for his marksman-focused shooting of 77 people by playing "World of Warcraft" for a year and then "Call of Duty" for 16 hours a day.

Research into this area goes back a half-century.

In 1954, researchers Peter Milner and James Olds discovered the pleasure center of the brain. In their experiments, an electrical current was sent to the limbic system of a rat's brain whenever it moved to a certain area of its cage. The limbic sytem is a portion of the brain that controls things like emotion, behavior and memory. The researchers hypothesized that if the stimulation to the limbic system were unpleasant, the rats would stay away from that part of the cage.

Surprisingly, the rats returned to that portion of the cage again and again, despite the sensation.

By

CNu

at

May 29, 2012

3

comments

![]()

Labels: addiction , reality casualties

Monday, May 28, 2012

Sunday, May 27, 2012

why TED is a massive money-soaked orgy of self-congratulatory futurism...,

The talk seemed reasonably well-received by the audience, but TED “curator” Chris Anderson told Hanauer that it would not be featured on TED’s site, in part because the audience response was mixed but also because it was too political and this was an “election year.”

Hanauer had his PR people go to the press immediately and accused TED of censorship, which is obnoxious — TED didn’t have to host his talk, obviously, and his talk was not hugely revelatory for anyone familiar with recent writings on income inequity from a variety of experts — but Anderson’s responses were still a good distillation of TED’s ideology.

In case you’re unfamiliar with TED, it is a series of short lectures on a variety of subjects that stream on the Internet, for free. That’s it, really, or at least that is all that TED is to most of the people who have even heard of it. For an elite few, though, TED is something more: a lifestyle, an ethos, a bunch of overpriced networking events featuring live entertainment from smart and occasionally famous people.

Before streaming video, TED was a conference — it is not named for a person, but stands for “technology, entertainment and design” — organized by celebrated “information architect” (fancy graphic designer) Richard Saul Wurman. Wurman sold the conference, in 2002, to a nonprofit foundation started and run by former publisher and longtime do-gooder Chris Anderson (not the Chris Anderson of Wired). Anderson grew TED from a woolly conference for rich Silicon Valley millionaire nerds to a giant global brand. It has since become a much more exclusive, expensive elite networking experience with a much more prominent public face — the little streaming videos of lectures.

It’s even franchising — “TEDx” events are licensed third-party TED-style conferences largely unaffiliated with TED proper — and while TED is run by a nonprofit, it brings in a tremendous amount of money from its members and corporate sponsorships. At this point TED is a massive, money-soaked orgy of self-congratulatory futurism, with multiple events worldwide, awards and grants to TED-certified high achievers, and a list of speakers that would cost a fortune if they didn’t agree to do it for free out of public-spiritedness.

According to a 2010 piece in Fast Company, the trade journal of the breathless bullshit industry, the people behind TED are “creating a new Harvard — the first new top-prestige education brand in more than 100 years.” Well! That’s certainly saying… something. (What it’s mostly saying is “This is a Fast Company story about some overhyped Internet thing.”)

To even attend a TED conference requires not just a donation of between $7,500 and $125,000, but also a complicated admissions process in which the TED people determine whether you’re TED material; so, as Maura Johnston says, maybe it’s got more in common with Harvard than is initially apparent.

Strip away the hype and you’re left with a reasonably good video podcast with delusions of grandeur. For most of the millions of people who watch TED videos at the office, it’s a middlebrow diversion and a source of factoids to use on your friends. Except TED thinks it’s changing the world, like if “This American Life” suddenly mistook itself for Doctors Without Borders.

The model for your standard TED talk is a late-period Malcolm Gladwell book chapter. Common tropes include:

- Drastically oversimplified explanations of complex problems.

- Technologically utopian solutions to said complex problems.

- Unconventional (and unconvincing) explanations of the origins of said complex problems.

- Staggeringly obvious observations presented as mind-blowing new insights.

What’s most important is a sort of genial feel-good sense that everything will be OK, thanks in large part to the brilliance and beneficence of TED conference attendees. (Well, that and a bit of Vegas magician-with-PowerPoint stagecraft.)

By

CNu

at

May 27, 2012

24

comments

![]()

Labels: agenda , elite , establishment

don't mention income inequality at TED

There’s one idea, though, that TED’s organizers recently decided was too controversial to spread: the notion that widening income inequality is a bad thing for America, and that as a result, the rich should pay more in taxes.

(RELATED: The Speech That's Too Hot for TED)

TED organizers invited a multimillionaire Seattle venture capitalist named Nick Hanauer – the first nonfamily investor in Amazon.com – to give a speech on March 1 at their TED University conference. Inequality was the topic – specifically, Hanauer’s contention that the middle class, and not wealthy innovators like himself, are America’s true “job creators.”

“We’ve had it backward for the last 30 years,” he said. “Rich businesspeople like me don’t create jobs. Rather they are a consequence of an ecosystemic feedback loop animated by middle-class consumers, and when they thrive, businesses grow and hire, and owners profit. That’s why taxing the rich to pay for investments that benefit all is a great deal for both the middle class and the rich.”

You can’t find that speech online. TED officials told Hanauer initially they were eager to distribute it. “I want to put this talk out into the world!” one of them wrote him in an e-mail in late April. But early this month they changed course, telling Hanauer that his remarks were too “political” and too controversial for posting.

Other TED talks posted online veer sharply into controversial and political territory, including NASA scientist James Hansen comparing climate change to an asteroid barreling toward Earth, and philanthropist Melinda Gates pushing for more access to contraception in the developing world.

TED curator Chris Anderson referenced the Gates talk in an e-mail to colleagues in early April, which was also sent to Hanauer, suggesting that he didn't want to release Hanauer’s talk at the same time as the one on contraception.

Hanauer’s talk “probably ranks as one of the most politically controversial talks we've ever run, and we need to be really careful when” to post it, Anderson wrote on April 6. “Next week ain't right. Confidentially, we already have Melinda Gates on contraception going out. Sorry for the mixed messages on this.”

In early May Anderson followed up with Hanauer to inform him he’d decided not to post his talk.

By

CNu

at

May 27, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: The Hardline , truth

Saturday, May 26, 2012

TED-Ed's customized learning web initiative

From the official press release:

Each video featured on the site is mapped, via tagging, to traditional subjects taught in schools and comes accompanied with supplementary materials that aid a teacher or student in using or understanding the video lesson. Supplementary materials include multiple-choice questions, open-answer questions, and links to more information on the topic.

But the most innovative feature of the site is that educators can customize these elements using a new functionality called “flipping.” When a video is flipped, the supplementary materials can be edited and the resulting lesson is rendered on a new and private web page. The creator of the lesson can then distribute it and track an individual student’s progress as they complete the assignment.

Yes, that means that anyone can create a lesson around a video, and then track that lesson for their students and/or publish the lesson so others could benefit from it. And — here’s the big kicker — you can create a lesson around any video on YouTube. TED-Ed could easily have locked you into their site’s content, but they’ve chosen instead to open their tools up to the whole wide world of YouTube videos.

The implications of this for online education are amazing: Any of the countless videos on YouTube right now could be made into a lesson, and of course you could upload a video of your own for the purpose as well. And it’s all completely free! How much easier has TED-Ed just made the lives of parents who homeschool?

This is all available right now, so check out the video above and then dive right in on the TED-Ed website! Fist tap Dale.

By

CNu

at

May 26, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: tactical evolution

disruptive innovation in education?

He’s not, however, tying up administrative loose ends before stepping down as director of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). Neither is he exchanging ideas with his collaborators on the major microchip-design project he’s leading, nor debating strategy with any of the other board members at Tilera, the chip company he founded in 2004.

Instead, he’s in an online discussion forum, talking about basic circuit design with students around the world — a group that includes high schoolers, undergraduates, mid-career professionals and at least one octogenarian retiree.

A decade ago, MIT broke ground with its OpenCourseWare initiative, which made MIT course materials, such as syllabi and lecture notes, publicly accessible. But over the last five years, MIT Provost L. Rafael Reif has led an effort to move the complete MIT classroom experience online, with video lectures, homework assignments, lab work — and a grade at the end.

That project, called MITx, launched late last year. On March 16, Reif announced that Agarwal would step down as CSAIL director in order to lead MIT’s Open Learning Enterprise, which will oversee MITx’s development.

MITx is born

“I’ve done a few startups, and even as a professor, you want to eat your own dog food,” Agarwal says. Hence his late-evening sessions on the bulletin board for MITx’s prototype course, “Circuits and Electronics.”

Co-taught by Agarwal, Panasonic Professor of Electrical Engineering Gerald Sussman, CSAIL co-director and Senior Lecturer Christopher Terman and CSAIL research scientist Piotr Mitros, the course — 6.002 in MIT’s course-numbering system, 6.002x in its MITx iteration — has more than 120,000 enrollees. Logged into the discussion forum as “aa,” Agarwal tests the MITx interface, gauges students’ reaction to online tools and sometimes answers their questions. Fist tap Dale.

By

CNu

at

May 26, 2012

1 comments

![]()

Labels: tactical evolution

Friday, May 25, 2012

Chipocalypse Now - I Love The Smell Of Deportations In The Morning

sky | Donald Trump has signalled his intention to send troops to Chicago to ramp up the deportation of illegal immigrants - by posting a...

-

theatlantic | The Ku Klux Klan, Ronald Reagan, and, for most of its history, the NRA all worked to control guns. The Founding Fathers...

-

NYTimes | The United States attorney in Manhattan is merging the two units in his office that prosecute terrorism and international narcot...

-

Wired Magazine sez - Biologists on the Verge of Creating New Form of Life ; What most researchers agree on is that the very first functionin...