Video - The Lightbulb Conspiracy 2010 documentary on planned obsolescence. Fist tap Umbrarchist.

Wednesday, August 03, 2011

the light bulb conspiracy

By

CNu

at

August 03, 2011

1 comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems , Peak Capitalism

Wednesday, July 06, 2011

r'lyeh mined?

Telegraph | Scientists have hailed a giant discovery that could end China's grasp on 97pc of the world's rare earth minerals - but unfortunately the vast new deposits are at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Explorers from Japan claim to have found more than 100bn tonnes of rare earth minerals, which are used in the manufacture of electronic goods like hybrid cars and flat-screen televisions.

Telegraph | Scientists have hailed a giant discovery that could end China's grasp on 97pc of the world's rare earth minerals - but unfortunately the vast new deposits are at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Explorers from Japan claim to have found more than 100bn tonnes of rare earth minerals, which are used in the manufacture of electronic goods like hybrid cars and flat-screen televisions.The sought-after deposits could spark a battle between Japan, Hawaii and Tahiti, which are near to where the minerals have been located.

Although in the middle of international water, the Japanese scientists claim the minerals can be easily extracted, having pinpointed their presence in sea mud across 78 locations up to 20,000 feet under the sea.

Yasuhiro Kato, an associate professor of earth science at the University of Tokyo, who led the explorers, said: "Just 0.4 square mile of deposits will be able to provide one-fifth of the current global annual consumption.

"Sea mud can be brought up to ships and we can extract rare earths right there using simple acid leaching. Using diluted acid, the process is fast, and within a few hours we can extract 80pc to 90pc of rare earths from the mud."

Rare earth metals have emerged as one of the most sought after resources in commodities boom. Minerals present in the mud include gadolinium, lutetium, terbium and dysprosium.

With demand increasingly outweighing supply, shortages of rare earth metals have triggered a string of mining ventures likened to a 21st century gold rush.

There has been much concern around China's control over global rare earth prices, trade restrictions and using its monopoly for political effect.

Japan accounts for a third of demand because of its strength in the electronics industry.

By

CNu

at

July 06, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems

Friday, May 20, 2011

hans rosling and the magic washing machine

TED | What was the greatest invention of the industrial revolution? Hans Rosling makes the case for the washing machine. With newly designed graphics from Gapminder, Rosling shows us the magic that pops up when economic growth and electricity turn a boring wash day into an intellectual day of reading.

By

CNu

at

May 20, 2011

1 comments

![]()

Labels: History's Mysteries , industrial ecosystems

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

america's achilles heel; the mississipi river's old river control structure

wunderground | America has an Achilles' heel. It lies on a quiet, unpopulated stretch of the Mississippi River in Louisiana, a few miles east of the tiny town of Simmesport. Rising up from the flat, wooded west flood plain of the Mississippi River tower four massive concrete and steel structures that would make a Pharaoh envious--the Army Corps' of Engineers greatest work, the billion-dollar Old River Control Structure. This marvel of modern civil engineering has, for fifty years, done what many thought impossible--impose man's will on the Mississippi River. Mark Twain, who captained a Mississippi river boat for many years, wrote in his book Life on the Mississippi, "ten thousand river commissions, with the mines of the world at their back, cannot tame that lawless stream, cannot curb it or define it, cannot say to it "Go here," or Go there, and make it obey; cannot save a shore which it has sentenced; cannot bar its path with an obstruction which it will not tear down, dance over, and laugh at." The great river wants to carve a new path to the Gulf of Mexico; only the Old River Control Structure keeps it at bay. Failure of the Old River Control Structure would be a severe blow to America's economy, interrupting a huge portion of our imports and exports that ship along the Mississippi River. Closure of the Mississippi to shipping would cost $295 million per day, said Gary LaGrange, executive director of the Port of New Orleans, during a news conference Thursday. The structure will receive its most severe test in its history in the coming two weeks, as the Mississippi River's greatest flood on record crests at a level never before seen.

wunderground | America has an Achilles' heel. It lies on a quiet, unpopulated stretch of the Mississippi River in Louisiana, a few miles east of the tiny town of Simmesport. Rising up from the flat, wooded west flood plain of the Mississippi River tower four massive concrete and steel structures that would make a Pharaoh envious--the Army Corps' of Engineers greatest work, the billion-dollar Old River Control Structure. This marvel of modern civil engineering has, for fifty years, done what many thought impossible--impose man's will on the Mississippi River. Mark Twain, who captained a Mississippi river boat for many years, wrote in his book Life on the Mississippi, "ten thousand river commissions, with the mines of the world at their back, cannot tame that lawless stream, cannot curb it or define it, cannot say to it "Go here," or Go there, and make it obey; cannot save a shore which it has sentenced; cannot bar its path with an obstruction which it will not tear down, dance over, and laugh at." The great river wants to carve a new path to the Gulf of Mexico; only the Old River Control Structure keeps it at bay. Failure of the Old River Control Structure would be a severe blow to America's economy, interrupting a huge portion of our imports and exports that ship along the Mississippi River. Closure of the Mississippi to shipping would cost $295 million per day, said Gary LaGrange, executive director of the Port of New Orleans, during a news conference Thursday. The structure will receive its most severe test in its history in the coming two weeks, as the Mississippi River's greatest flood on record crests at a level never before seen.

By

CNu

at

May 17, 2011

6

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems , weather report

the century of disasters

Slate | All of these things have the common feature of low probability and high consequence. They're "black swan" events. They're unpredictable in any practical sense. They're also things that ordinary people probably should not worry about on a daily basis. You can't fear the sun. You can't worry that a rock will fall out of the sky and smash the earth, or that the ground will open up and swallow you like a vitamin. A key element of maintaining one's sanity is knowing how to ignore risks that are highly improbable at any given point in time.

Slate | All of these things have the common feature of low probability and high consequence. They're "black swan" events. They're unpredictable in any practical sense. They're also things that ordinary people probably should not worry about on a daily basis. You can't fear the sun. You can't worry that a rock will fall out of the sky and smash the earth, or that the ground will open up and swallow you like a vitamin. A key element of maintaining one's sanity is knowing how to ignore risks that are highly improbable at any given point in time.And yet in the coming century, these or other black swans will seem to occur with surprising frequency. There are several reasons for this. We have chosen to engineer the planet. We have built vast networks of technology. We have created systems that, in general, work very well, but are still vulnerable to catastrophic failures. It is harder and harder for any one person, institution, or agency to perceive all the interconnected elements of the technological society. Failures can cascade. There are unseen weak points in the network. Small failures can have broad consequences.

Advertisement

Most importantly: We have more people, and more stuff, standing in the way of calamity. We're not suddenly having more earthquakes, but there are now 7 billion of us, a majority living in cities. In 1800, only Beijing could count a million inhabitants, but at last count there were 381 cities with at least 1 million people. Many are "megacities" in seismically hazardous places—Mexico City, Caracas, Tehran, and Kathmandu being among those with a lethal combination of weak infrastructure (unreinforced masonry buildings) and a shaky foundation.

Natural disasters will increasingly be accompanied by technological crises—and the other way around. In March, the Japan earthquake triggered the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant meltdown. Last year, a technological failure on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico led to the environmental crisis of the oil spill. (I chronicle the Deepwater Horizon blowout and the ensuing crisis management in a new book: A Hole at the Bottom of the Sea: The Race to Kill the BP Oil Gusher.)

In both the Deepwater Horizon and Fukushima disasters, the safety systems weren't nearly as robust as the industries believed. In these technological accidents, there are hidden pathways for the gremlins to infiltrate the operation. In the case of Deepwater Horizon, a series of decisions by BP and its contractors led to a loss of well control—the initial blowout. The massive blowout preventer on the sea floor was equipped with a pair of pinchers known as blind shear rams. They were supposed to cut the drillpipe and shear the well. The forensic investigation indicated that the initial eruption of gas buckled the pipe and prevented the blind shear rams from getting a clean bite on it. So the "backup" plan—cut the pipe—was effectively eliminated in the initial event, the loss of well control.

Fukushima also had a backup plan that wasn't far enough back. The nuclear power plant had backup generators in case the grid went down. But the generators were on low ground, and were blasted by the tsunami. Without electricity, the power company had no way to cool the nuclear fuel rods. In a sense, it was a very simple problem: a power outage. Some modern reactors coming online have passive cooling systems for backups—they rely on gravity and evaporation to circulate the cooling water. Fist tap Nana.

By

CNu

at

May 17, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Labels: clampdown , industrial ecosystems

Tuesday, May 03, 2011

the world's last typewriter factory closes in india

Business Insider | Obsolete technologies don't die right away, they just move to places like India. Such was the case with typewriters, which were produced by Godrej & Boyce in Mumbai until recently.

Business Insider | Obsolete technologies don't die right away, they just move to places like India. Such was the case with typewriters, which were produced by Godrej & Boyce in Mumbai until recently.Now the typewriter era is officially over.

Godrej & Boyce's Milind Dukle tells the Business Standard:

"From the early 2000 onwards, computers started dominating. All the manufacturers of office typewriters stopped production, except us. Till 2009, we used to produce 10,000 to 12,000 machines a year.

"We stopped production in 2009 and were the last company in the world to manufacture office typewriters. Currently, the company has only 500 machines left. The machines are of Godrej Prima, the last typewriter brand from our company, and will be sold at a maximum retail price of Rs 12,000."

The factory has been converted to a refrigerator manufacturing unit.

By

CNu

at

May 03, 2011

4

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems

Saturday, April 30, 2011

dimming of the globe...,

FCNP | Late last month a newly enhanced web site, www.energyshortage.org, dedicated to collecting articles concerning energy shortages around the world reappeared on the web after an absence of some months. The stories deal with coal, electricity and natural gas shortages as well as oil. In the course of the past month the web site has located and linked to nearly 200 stories that deal with some aspect of the developing global energy shortage. Most of these stories come from local paper and taken together paint a distressing picture of looming societal breakdown in many parts of the world that is not as yet generally appreciated by the public.

Most of the problems reported on deal with electricity shortages - which in several countries have deteriorated to the point where economies are threatened with collapse. In South Asia - Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and later in India - a combination of too many people, hydro-power reducing droughts, depleting fossil fuel reserves and inadequate investment in infrastructure raises the possibility that many urban areas may soon be uninhabitable.

In Pakistan the electricity is now turned off for 18-20 hours some days in many cities and 20 hours in rural villages. The onset of summer temperatures, shortages of fuel oil for thermal generation and falling water levels have increased the power shortfall to record levels. Without electricity to run the pumps urban water supplies quickly shut down. Without power to run the mills, exports are falling, leaving the country without money to import oil. In short we are seeing a classical downward spiral. The lack of electricity to sell is creating serious hardships for electricity companies which can no longer afford to pay for energy - coal, oil, or natural gas - and are being shut off by suppliers.

Pakistan is hoping that increased imports of liquefied natural gas which is for now is relatively plentiful, transportable, and affordable will be a short term solution for economic survival. Over the longer run natural gas pipelines from Iran and Turkmenistan may help someday provided the numerous dissident groups in the area don't blow them up. Demand for electricity in Pakistan is growing at 6-7 percent a year and all agree that building more dams is the best long term solution. This of course requires prodigious amounts of capital and the cooperation of Mother Nature to supply the necessary rains in an era of rapidly changing climatic conditions.

At the other side of the subcontinent is Bangladesh, a country of 158 million people and minimal natural resources. The country is currently generating 4,000 megawatts vs. a demand of 5,500 resulting in rolling blackouts across the country. The real problem however comes in keeping the fresh water flowing. Only half of Dhaka's 577 water pumps are equipped with back-up generators. Falling water tables and falling energy supplies suggest that major humanitarian disasters are not far away.

In the center of the sub-continent lies Nepal. Here the problem is 14 hours a day without power coupled with the inability to pay the Indian oil company for imported oil and gas. The Indians recently reduced fuel supplies to Nepal by 60 percent until the 1.25 billion rupee fuel bill is paid. There is no obvious way out of this situation.

Finally we get to India with its 1.2 billion people and 8 percent annual GDP growth. Although the country has sizeable reserves of coal, oil and natural gas, these are not adequate for a country of this size and rate of growth. Domestic coal production is not meeting the needs of a rapidly growing economy. This year the coal shortfall may be as much as 142 million tons as compared to needs. A few years from now it could be 250 million tons. Rolling blackouts have begun in some parts of the country and the projected demand for ever increasing amounts of expensive imported coal extends into the indefinite future.

China too seems to be facing coal and oil shortages this summer. Despite coal production of 3.2 billion tons a year, this is not sufficient to support the demand for electricity which is increasing at circa 11 percent a year. Beijing, of course, can afford to import all the coal, oil, and natural gas it needs and probably will. The problem will come with local shortages that may force companies to resort to emergency diesel power generation and thereby increase China's demand for imported oil.

By

CNu

at

April 30, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems , unintended consequences

Sunday, March 27, 2011

anthropocene

National Geographic | The word "Anthropocene" was coined by Dutch chemist Paul Crutzen about a decade ago. One day Crutzen, who shared a Nobel Prize for discovering the effects of ozone-depleting compounds, was sitting at a scientific conference. The conference chairman kept referring to the Holocene, the epoch that began at the end of the last ice age, 11,500 years ago, and that—officially, at least—continues to this day.

National Geographic | The word "Anthropocene" was coined by Dutch chemist Paul Crutzen about a decade ago. One day Crutzen, who shared a Nobel Prize for discovering the effects of ozone-depleting compounds, was sitting at a scientific conference. The conference chairman kept referring to the Holocene, the epoch that began at the end of the last ice age, 11,500 years ago, and that—officially, at least—continues to this day."'Let's stop it,'" Crutzen recalls blurting out. "'We are no longer in the Holocene. We are in the Anthropocene.' Well, it was quiet in the room for a while." When the group took a coffee break, the Anthropocene was the main topic of conversation. Someone suggested that Crutzen copyright the word.

Way back in the 1870s, an Italian geologist named Antonio Stoppani proposed that people had introduced a new era, which he labeled the anthropozoic. Stoppani's proposal was ignored; other scientists found it unscientific. The Anthropocene, by contrast, struck a chord. Human impacts on the world have become a lot more obvious since Stoppani's day, in part because the size of the population has roughly quadrupled, to nearly seven billion. "The pattern of human population growth in the twentieth century was more bacterial than primate," biologist E. O. Wilson has written. Wilson calculates that human biomass is already a hundred times larger than that of any other large animal species that has ever walked the Earth.

In 2002, when Crutzen wrote up the Anthropocene idea in the journal Nature, the concept was immediately picked up by researchers working in a wide range of disciplines. Soon it began to appear regularly in the scientific press. "Global Analysis of River Systems: From Earth System Controls to Anthropocene Syndromes" ran the title of one 2003 paper. "Soils and Sediments in the Anthropocene" was the headline of another, published in 2004.

At first most of the scientists using the new geologic term were not geologists. Zalasiewicz, who is one, found the discussions intriguing. "I noticed that Crutzen's term was appearing in the serious literature, without quotation marks and without a sense of irony," he says. In 2007 Zalasiewicz was serving as chairman of the Geological Society of London's Stratigraphy Commission. At a meeting he decided to ask his fellow stratigraphers what they thought of the Anthropocene. Twenty-one of 22 thought the concept had merit.

The group agreed to look at it as a formal problem in geology. Would the Anthropocene satisfy the criteria used for naming a new epoch? In geologic parlance, epochs are relatively short time spans, though they can extend for tens of millions of years. (Periods, such as the Ordovician and the Cretaceous, last much longer, and eras, like the Mesozoic, longer still.) The boundaries between epochs are defined by changes preserved in sedimentary rocks—the emergence of one type of commonly fossilized organism, say, or the disappearance of another.

The rock record of the present doesn't exist yet, of course. So the question was: When it does, will human impacts show up as "stratigraphically significant"? The answer, Zalasiewicz's group decided, is yes—though not necessarily for the reasons you'd expect.

By

CNu

at

March 27, 2011

4

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems

Friday, March 25, 2011

alternative fuels useless to the military

NYTimes | The United States would derive no meaningful military benefit from increased use of alternative fuels to power its jets, ships and other weapons systems, according to a government-commissioned study by the RAND Corporation scheduled for release Tuesday.

NYTimes | The United States would derive no meaningful military benefit from increased use of alternative fuels to power its jets, ships and other weapons systems, according to a government-commissioned study by the RAND Corporation scheduled for release Tuesday.The report also argued that most alternative-fuel technologies were unproven, too expensive or too far from commercial scale to meet the military’s needs over the next decade.

In particular, the report argued that the Defense Department was spending too much time and money exploring experimental biofuels derived from sources like algae or the flowering plant camelina, and that more focus should be placed on energy efficiency as a way of combating greenhouse gas emissions.

The report urged Congress to reconsider the military’s budget for alternative-fuel projects. But if such fuels are to be pursued, the report concluded, the most economic, environmentally sound and near-term candidate would be a liquid fuel produced using a combination of coal and biomass, as well as some method for capturing and storing carbon emissions released during production.

The findings by the nonprofit research group, which grew out of a directive in the 2009 Defense Authorization Act calling for further study of alternative fuels in military vehicles and aircraft, are likely to provoke much debate in Washington.

The Obama administration has directed billions of dollars to support emerging clean-energy technologies even as Congress has been unwilling to pass any sort of climate or renewable energy legislation.

Meanwhile, the Pentagon is seeking to improve the military’s efficiency and reduce its reliance on fossil fuels over the coming decade, devoting $300 million in economic stimulus financing and other research money toward those goals.

RAND’s conclusions drew swift criticism from some branches of the military — particularly the Navy, which has been leading the foray into advanced algae-based fuels.

By

CNu

at

March 25, 2011

3

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems , killer-ape , psychopathocracy

Tuesday, March 22, 2011

A Review of Joe Bageant's Rainbow Pie: A Redneck Memoir

JoeBaegent | Q: How do you know if you are rich, middle class or poor in America?

JoeBaegent | Q: How do you know if you are rich, middle class or poor in America?A: When you go to work, if your name is on the building -- you’re rich; if your name is on an office door -- you’re middle class; if your name is on your shirt -- you're poor…and, if someone else’s name is on your hand-me-down work shirt.

You always hear about natural-born musicians, artists, teachers, nurses, even businessmen. But what happened to the natural-born farmer and extended farm family when the rural-to-urban migration saw us go from 92% of Americans making their living (and dying) on the land in 1900 to around 2% today? What happened to the natural sense of community that engendered -- that "we're all in it together," culture we now long for? And, what about America's supposedly classless society? How's that working out for ya?

Joe’s memoir begins in 1951 at grandparents Maw and Pap’s small farm along Shanghai (it’s an Irish term) Road in Morgan County, West Virginia. Like many a homestead along the Blue Ridge Mountains, it was a multi-generational subsistence farm (“the farm was not a business”) that had been the norm in America before the great corporate-driven rural-to-urban shift that coincided with the end of World War Two.

Joe’s childhood days “Over Home” were whiled away on the usual attendant chores, hand-picking bugs off garden crops, watching Pap plow fields behind his draught horse or hand-harvest the large cornfield, sweating away with the adults during the all-hands-on-deck haying and wood cutting, helping with the late Autumn hog butchering, dodging the ever-present snakes and bullying older cousins and hunting with the adults or developing future hunting skills plinking holes in a broken metal bucket set on a fencepost.

A Multi-faceted American Tragedy

For the Christian teetotaler Pap -- who likely never brought in more than $1000 in any given year -- freedom “resided in yeoman property rights” -- the Jeffersonian ideal of an Agrarian Democracy. No one in Maw and Pap's hard-working extended family ever went hungry or homeless. As Joe notes, this rural system of subsistence farming and barter right up the great rural-to-urban migration was “an economy whose currency was the human calorie.”

And, that’s what this book is all about: the post WWII shift from Maw and Pap’s agrarian democracy to the urban-dominated/techno/bureaucratic/military/security/consumer Empire of today. He writes how that shift and the resulting class stratification has led us to the brink of economic and ecological collapse.

Joe notes: “Damn few of us grasp how the loss of traditional aesthetic and foundational values, the yeoman tradition, are connected with so much modern American tragedy.”

The rush to “agri-business;” the obesity/diabetes health crisis; the out-migration to teeming cities; the resulting army of disposable laborers; the meth epidemic devastating the “white working-class’s futureless young”… all are tragedies personal and political. It’s also the root of our ecological crisis. You just can’t have “ten thousand years of agriculture synthesized into money” without it. Joe posits, “In all likelihood, there is no solution for environmental destruction that does not first require a healing of the damage done to the human community.”

By

CNu

at

March 22, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Labels: History's Mysteries , industrial ecosystems

the human costs of different types of energy

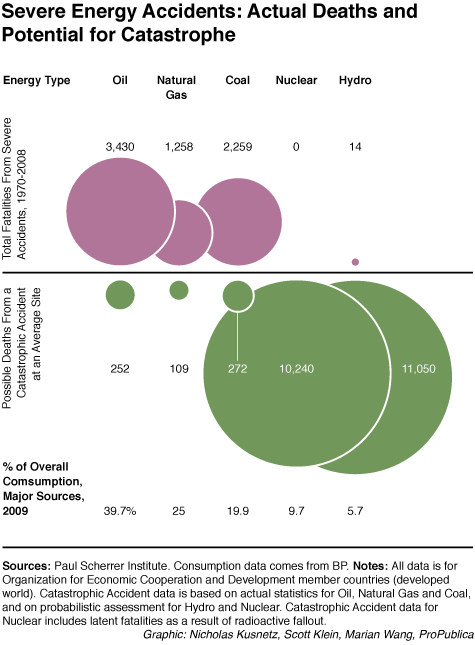

Propublica | Since this time last year, we’ve seen a deadly mine disaster [1], the worst oil spill in U.S. history [2], and now a nuclear crisis in Japan [3]. That got us wondering—how does one compare or quantify the human cost of different sources of energy?

Propublica | Since this time last year, we’ve seen a deadly mine disaster [1], the worst oil spill in U.S. history [2], and now a nuclear crisis in Japan [3]. That got us wondering—how does one compare or quantify the human cost of different sources of energy?As it turns out, a Swiss research organization, the Paul Sherrer Institute, has been doing just that. Using data from the institute, we pulled together a few visualizations.

The top part of the graph shows the actual number of deaths from severe accidents in developed countries [4] from 1970 through 2008. The bottom part of the graph shows the number of deaths that might result [5] from a catastrophic event at an average site in the developed world. This does not show the worst case scenario for any situation, but it gives a sense of the relative risks associated with different sources of energy.

These numbers represent deaths in the developed world from severe accidents only, where at least five people were killed. The accidents have occurred at many stages of the energy supply chain, from coal mining to shipping oil to accidents at actual power plants.

It’s important to note that every-day energy use from fossil fuels kills far more people than accidents. By one estimate from 2000, pollution from power plants results in at least 30,000 premature deaths every year [6] in the United States alone.

By

CNu

at

March 22, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems

Monday, March 14, 2011

the right to economic development in the arab world

RWER | At this juncture in Arab history, there is an opportunity to be grasped. Unless there is a successful transition from the political to the social revolution in the Arab world, the sacrifice made by the Arab working classes will be betrayed. The following is a proposal to expose some of the previous aspects of development and economic performance in the Arab world with the aim to infuse the development debate with the idea of development as a human right. It need not be said, the present struggle is a struggle for rights. The idea of rights empowers people; it gives them a sense of self-affirmation. The language of rights establishes a framework for the allocation of resources. Without the rights rhetoric we will end up with a totally uncaring market system that will not solve our problems.

RWER | At this juncture in Arab history, there is an opportunity to be grasped. Unless there is a successful transition from the political to the social revolution in the Arab world, the sacrifice made by the Arab working classes will be betrayed. The following is a proposal to expose some of the previous aspects of development and economic performance in the Arab world with the aim to infuse the development debate with the idea of development as a human right. It need not be said, the present struggle is a struggle for rights. The idea of rights empowers people; it gives them a sense of self-affirmation. The language of rights establishes a framework for the allocation of resources. Without the rights rhetoric we will end up with a totally uncaring market system that will not solve our problems.In the Arab world, economic policies are concentrated in the competence of the state. It is the efficiency and practicality of public policies that should be accountable and come under independent public scrutiny. The role of economic policy and, more specifically, fiscal and monetary policy is to find the appropriate regime that mediates disparate developments and puts interest back in the national and regional economies. Under the right to development rubric, economic growth should meet basic needs and not be a trickle down arrangement. Also, the Arab world is a world that is so interlocked with the global economy, such that, it would not be possible to lock in resources for development without international cooperation. The international community, comprising countries and institutions at the international level, has the responsibility to create a global environment conducive for development.

By virtue of their acceptance and commitment to the legal instruments, the members of the international community have the obligation to support effectively the efforts of Arab States that set for themselves the goal of realizing human rights, including the right to development, through trade, investment, financial assistance and technology transfer. Without this rudimentary cornerstone of an economic strategy designed to reduce poverty and unemployment, it is unlikely that any economic program of action can meet the basics of human rights, compensate working people for their suffering under the combined assault of neoliberalism and Arab autocracy and, generally, to secure the right to development.

By

CNu

at

March 14, 2011

37

comments

![]()

Labels: hardscrabble , hegemony , industrial ecosystems

Thursday, February 10, 2011

oil tankers in the wake of the egyptian crisis

Peak Oil News | Gail Tverberg’s analysis of some of the underlying causes of the current Egyptian crisis is cogent, but one of the other consequences caught my attention today. For, as was noted in Forbes

Peak Oil News | Gail Tverberg’s analysis of some of the underlying causes of the current Egyptian crisis is cogent, but one of the other consequences caught my attention today. For, as was noted in ForbesWhile most equity-related assets got battered, a select group of stocks, oil shippers, were corking champagne bottles. Apart from Overseas Shipholding, Frontline Ltd. had a killer day, gaining 7.8% or $1.96 to $27.10.The change involved is not just giving a tanker captain a different map and saying “get on with it.” Because of the relative size of the Suez Canal, there are different sizes of tankers involved, and so I thought it useful to talk about the different sizes of tankers, how fast and where they go, (and what the cost of that re-routing might be) in the post today.

An analyst for a shipping hedge fund explained that the spike is connected to fears surrounding the continued operations of the Suez Canal, amidst social unrest caused by massive riots against President Hosni Mubarak’s 30 year rule. “While Suez closure is not much of a threat, shippers are refusing to load in the Red Sea and transit the Canal,” explained the trader. “What’s probably going to happen is that they re-rout ships to the Cape [of Good Hope],” he noted.

“[Re-routing] makes voyages longer, which ties up ships and in turn diminishes supply,” said the analyst, “[this] is positive for the tanker market."

To begin with let’s look at the traffic along the Suez Canal itself. Note that there is no immediate port of access into the Mediterranean, and thus to Europe, from Saudi Arabia or the nations of the Gulf. Fist tap Big Don

By

CNu

at

February 10, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems

Thursday, December 30, 2010

the imminent collapse of industrial society - redux

CounterCurrents | The collapse of modern industrial society has 14 parts, each with a somewhat causal relationship to the next. (1) Fossil fuels, (2) metals, and (3) electricity are a tightly-knit group, and no industrial civilization can have one without the others. The decline in fossil-fuel production is the most critical aspect of the collapse, and most of the following text will be devoted to that topic. As those three disappear, (4) food and (5) fresh water become scarce; grain and wild fish supplies per capita have been declining for years, water tables are falling everywhere, rivers are not reaching the sea. Matters of infrastructure then follow: (6) transportation and (7) communication - no paved roads, no telephones, no computers. After that, the social structure begins to fail: (8) government, (9) education, and (10) the large-scale division of labor that makes complex technology possible.

After these 10 parts, however, there are four others that form a separate layer, in some respects more psychological or sociological. We might call these “the four Cs.” The first three are (11) crime, (12) cults, and (13) craziness - the breakdown of traditional law; the ascendance of dogmas based on superstition, ignorance, cruelty, and intolerance; the overall tendency toward anti-intellectualism; and the inability to distinguish mental health from mental illness. There is also a final and more general part that is (14) chaos, resulting in the pervasive sense that “nothing works any more.”

These are cascading dominoes; all parts of the collapse have more to do with causality than with chronology, although there is no great distinction to be made between the two. If we look at matters from a more purely chronological viewpoint, however, we can say that there is a clear division into two time periods, two phases. The first phase will be merely economic hardship, and the second will be entropy. In the first phase the major issues will be inflation, unemployment, and the stock market. The second phase will be characterized by the disappearance of money, law, and government. In more pragmatic terms, we can say that the second phase will begin when money is no longer accepted as a means of exchange. (We last took note of Peter Goodchild at the very end of 2007 writing about Dunbar's Number)

By

CNu

at

December 30, 2010

0

comments

![]()

Labels: de-evolution , industrial ecosystems , unintended consequences

systemic collapse

Countercurrents | Systemic collapse, societal collapse, the coming dark age, the great transformation, the coming crash, the post-industrial age, the long emergency, socioeconomic collapse, the die-off, the tribulation, the coming anarchy, perhaps even resource wars (to the extent that this is not an oxymoron, since wars themselves require resources) ― there are many names, and they do not all correspond to exactly the same thing, but there is a widespread belief that something immense and ominous is happening. Unlike those of the Aquarian Age, the heralds of this new era often have impressive academic credentials: they include scientists, engineers, and historians. The serious beginnings of the concept can be found in Paul and Anne Ehrlich, Population, Resources, Environment (1970); Donella H. Meadows et al., The Limits to Growth (1972); and William R. Catton, Jr., Overshoot (1980). What all the overlapping theories have in common can be seen in the titles of those three books.

Oil depletion is the most critical aspect in the systemic collapse of modern civilization, but altogether this collapse has about 10 principal parts, each with a vaguely causal relationship to the next. Oil, metals, and electricity are a tightly-knit group, as we shall see, and no industrial civilization can have one without the others. As those 3 disappear, food and fresh water become scarce (fish and grain supplies per capita have been declining for years, water tables are falling everywhere, rivers are not reaching the sea). These 5 can largely be considered as resource depletion, and the converse of resource depletion is environmental destruction. Disruption of ecosystems in turn leads to epidemics. Matters of infrastructure then follow: transportation and communication. Social structure is next to fail: without roads and telephones, there can be no government, no education, no large-scale division of labor. After the above 10 aspects of systemic collapse, there is another layer, in some respects more psychological or sociological, that we might call “the 4 Cs.” The first 3 are crime (war and crime will be indistinguishable, as Robert D. Kaplan explains), cults, and craziness — the breakdown of traditional law, the tendency toward anti-intellectualism, the inability to distinguish mental health from mental illness. After that there is a more general one that is simple chaos, which results in the pervasive sense that “nothing works any more.”

Systemic collapse, in turn, has one overwhelming cause: world overpopulation. All of the flash-in-the-pan ideas that are presented as solutions to the modern dilemma — solar power, ethanol, hybrid cars, desalination, permaculture — have value only as desperate attempts to solve an underlying problem that has never been addressed in a more direct manner. American foreign aid, however, has always included only trivial amounts for family planning; the most powerful country in the world has done very little to solve the biggest problem in the world.

By

CNu

at

December 30, 2010

8

comments

![]()

Labels: contraction , Hanson's Peak Capitalism , industrial ecosystems

Saturday, December 04, 2010

eroei the quintessence of "economics"

ScienceDaily | The worst recessions of the last 65 years were preceded by declines in energy quality for oil, natural gas, and coal. Energy quality is plotted using the energy intensity ratio (EIR) for each fuel. Recessions are indicated by gray bars. In layman's terms, EIR measures how much profit is obtained by energy consumers relative to energy producers.The higher the EIR, the more economic value consumers (including businesses, governments and people) get from their energy. An overlooked cause of the economic recession in the U.S. is a decade long decline in the quality of the nation's energy supply, often measured as the amount of energy we get out for a given energy input, says energy expert Carey King of The University of Texas at Austin.

ScienceDaily | The worst recessions of the last 65 years were preceded by declines in energy quality for oil, natural gas, and coal. Energy quality is plotted using the energy intensity ratio (EIR) for each fuel. Recessions are indicated by gray bars. In layman's terms, EIR measures how much profit is obtained by energy consumers relative to energy producers.The higher the EIR, the more economic value consumers (including businesses, governments and people) get from their energy. An overlooked cause of the economic recession in the U.S. is a decade long decline in the quality of the nation's energy supply, often measured as the amount of energy we get out for a given energy input, says energy expert Carey King of The University of Texas at Austin.Many economists have pointed to a bursting real estate bubble as the initial trigger for the current recession, which in turn caused global investments in U.S. real estate to turn sour and drag down the global economy. King suggests the real estate bubble burst because individuals were forced to pay a higher and higher percentage of their income for energy -- including electricity, gasoline and heating oil -- leaving less money for their home mortgages.

In economic terms, the quality of the nation's energy supply is referred to as Energy Return on Energy Investment (EROI). For example, if an oil company uses a 10th of a barrel of oil to drill, pump, transport and refine one barrel of oil, the EROI for the refined fuel is 10.

"Many economists don't think of energy as being a limiting factor to economic growth," says King, a research associate in the university's Center for International Energy and Environmental Policy. "They think continual improvements in technology and efficiency have completely decoupled the two factors. My research is part of a growing body of evidence that says that's just not true. Energy still plays a big role."

By

CNu

at

December 04, 2010

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

africa's infrastructure deficit creates economic opportunity

Mmegi | The Development Bank of Southern Africa executive coordinator Lesetsa Matshekga said that the continent's biggest infrastructure deficit existed within the power generation sector. He noted that around 22, 000 MW of crossborder transmission lines would be needed within the next couple of years. While sub-Saharan Africa was home to 800-million people, it generated the same quantum of power as Spain.

Mmegi | The Development Bank of Southern Africa executive coordinator Lesetsa Matshekga said that the continent's biggest infrastructure deficit existed within the power generation sector. He noted that around 22, 000 MW of crossborder transmission lines would be needed within the next couple of years. While sub-Saharan Africa was home to 800-million people, it generated the same quantum of power as Spain.Physical infrastructure remains Africa's most significant constraint as far as economic development goes, however, the backlog also represents big investment and business opportunities head of research and information at South Africa's Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), Jorge Maia, said. Speaking at the Gordon Institute of Business Science Business of Africa conference in Johannesburg, Maia said that some $93-billion a year was needed to build infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa alone.

With the region expected to show economic growth of 5,5% a year over the next five years, the development of infrastructure creates a wealth of opportunity.

"As the region and Africa keeps on growing, this infrastructure gap will just become more evident," said Maia.

There are several limiting factors that come into play in the development of infrastructure on the continent, the most significant of which is a large funding gap.

However, AngloGold Ashanti CEO Mark Cutifani said at the conference that private companies could, to a large extent, assist in bridging some of these funding gaps.

"If African governments and private enterprises are able to work together, and form public-private partnerships, this can fill the gap to some extent."

Cutifani emphasised that infrastructure cooperation and an enabling environment created by governments across the continent were imperative for the future development of Africa.

"The time has come to develop infrastructure beyond colonial borders in Africa, from east to west and from north to south."

Maia agreed, but added that Africa also had to rethink the pricing of its existing infrastructure and services. He pointed out that Africa was the most expensive continent to transport goods.

"This is something that can easily be readjusted."

By

CNu

at

November 23, 2010

0

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems

Saturday, November 13, 2010

oil will run dry before substitutes roll out

Physorg | At the current pace of research and development, global oil will run out 90 years before replacement technologies are ready, says a new University of California, Davis, study based on stock market expectations.

Physorg | At the current pace of research and development, global oil will run out 90 years before replacement technologies are ready, says a new University of California, Davis, study based on stock market expectations.The forecast was published online Monday (Nov. 8) in the journal Environmental Science & Technology. It is based on the theory that long-term investors are good predictors of whether and when new energy technologies will become commonplace.

"Our results suggest it will take a long time before renewable replacement fuels can be self-sustaining, at least from a market perspective," said study author Debbie Niemeier, a UC Davis professor of civil and environmental engineering.

Niemeier and co-author Nataliya Malyshkina, a UC Davis postdoctoral researcher, set out to create a new tool that would help policymakers set realistic targets for environmental sustainability and evaluate the progress made toward those goals.

Two key elements of the new theory are market capitalizations (based on stock share prices) and dividends of publicly owned oil companies and alternative-energy companies. Other analysts have previously used similar equations to predict events in finance, politics and sports.

"Sophisticated investors tend to put considerable effort into collecting, processing and understanding information relevant to the future cash flows paid by securities," said Malyshkina. "As a result, market forecasts of future events, representing consensus predictions of a large number of investors, tend to be relatively accurate."

Niemeier said the new study's findings are a warning that current renewable-fuel targets are not ambitious enough to prevent harm to society, economic development and natural ecosystems.

"We need stronger policy impetus to push the development of these alternative replacement technologies along," she said.

By

CNu

at

November 13, 2010

0

comments

![]()

Labels: industrial ecosystems , Irreplaceable Natural Material Resources , What Now?

Friday, November 12, 2010

the privatization of war: mercenaries, private military and security companies (PMSC)

globalresearch | In 1961, President Eisenhower warned the American public opinion against the growing danger of a military industrial complex stating: “(…) we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defence with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together”.

globalresearch | In 1961, President Eisenhower warned the American public opinion against the growing danger of a military industrial complex stating: “(…) we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defence with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together”.Fifty years later, on 8 September 2001, Donald Rumsfeld in his speech in the Department of Defence warned the militaries of the Pentagon against “an adversary that poses a threat, a serious threat, to the security of the United States of America (…) Let's make no mistake: The modernization of the Department of Defense is (…) a matter of life and death, ultimately, every American's. (…) The adversary. (…) It's the Pentagon bureaucracy. (…)That's why we're here today challenging us all to wage an all-out campaign to shift Pentagon's resources from bureaucracy to the battlefield, from tail to the tooth. We know the adversary. We know the threat. And with the same firmness of purpose that any effort against a determined adversary demands, we must get at it and stay at it. Some might ask, how in the world could the Secretary of Defense attack the Pentagon in front of its people? To them I reply, I have no desire to attack the Pentagon; I want to liberate it. We need to save it from itself."

Rumsfeld should have said the shift from the Pentagon’s resources from bureaucracy to the private sector. Indeed, that shift had been accelerated by the Bush Administration: the number of persons employed by contract which had been outsourced (privatized) by the Pentagon was already four times more than at the Department of Defense.

It is not anymore a military industrial complex but as Noam Chomsky has indicated "it's just the industrial system operating under one or another pretext”.

The articles of the Washington Post “Top Secret America: A hidden world, growing beyond control”, by Dana Priest and William M. Arkin (19 July 2010) show the extent that “The top-secret world the government created in response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, has become so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist within it or exactly how many agencies do the same work”.

The investigation's findings include that some 1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in about 10,000 locations across the United States; and that an estimated 854,000 people, nearly 1.5 times as many people as live in Washington, D.C., hold top-secret security clearances. A number of private military and security companies are among the security and intelligence agencies mentioned in the report of the Washington Post.

The Working Group received information from several sources that up to 70 per cent of the budget of United States intelligence is spent on contractors. These contracts are classified and very little information is available to the public on the nature of the activities carried out by these contractors.

The privatization of war has created a structural dynamic, which responds to a commercial logic of the industry.

By

CNu

at

November 12, 2010

0

comments

![]()

Labels: de-evolution , industrial ecosystems , psychopathocracy

Tuesday, November 02, 2010

can we save america's crumbling water system?

Infrastructurist | Water infrastructure may not be a sexy topic, but it’s becoming an important one. The American Society of Civil Engineers recently gave America’s drinking-water systems a grade of D-minus. Roughly 10 billion gallons of sewage seep into these crumbling pipes each year. The Obama administration has secured $6 billion for improvements, but the Environmental Protection Agency puts the true cost of fixing water infrastructure at roughly $335 billion. That figure seems staggering until we consider that parts of the country’s water system were built circa the Civil War.

Infrastructurist | Water infrastructure may not be a sexy topic, but it’s becoming an important one. The American Society of Civil Engineers recently gave America’s drinking-water systems a grade of D-minus. Roughly 10 billion gallons of sewage seep into these crumbling pipes each year. The Obama administration has secured $6 billion for improvements, but the Environmental Protection Agency puts the true cost of fixing water infrastructure at roughly $335 billion. That figure seems staggering until we consider that parts of the country’s water system were built circa the Civil War.It doesn’t take Abraham Lincoln to see the problem: people have never paid enough for their water, as this public service announcement points out, and they aren’t ready to start now. Attempts to raise utility rates for water systems in several cities across the country have been met with outrage. And because water pipes are out of sight, “no one really understands how bad things have become,” a member of the National Drinking Water Advisory Council told the New York Times in March:

“We’re relying on water systems built by our great-grandparents, and no one wants to pay for the decades we’ve spent ignoring them.”

A recent Newsweek cover story about the world’s water crisis (yes there’s still a Newsweek, for now) reports that some U.S. cities have been forced to privatize their water supplies. The shift enables officials to offload huge maintenance costs while promising jobs. But the colossal nature of water infrastructure lends itself to monopolization, and because water systems are underground they’re difficult for governments to monitor. In fact, Newsweek reports, some cities have grown so dismayed with privatized water that they’ve engaged in costly litigation to cancel the contracts.

The public may finally be ready to shoulder some of the burden. The results of a new survey, released earlier this week by ITT Corporation, suggest that people are willing to pay a little more—just a little—to keep the country’s water pipes from crumbling. (It should be noted that ITT deals in water infrastructure.) While 69 percent of survey respondents agreed that they take their access to clean water for granted, about two-thirds said they would be willing to pay $6.20 more per month to improve their water systems. If applied to all households across the country, such an increase comes to $5.4 billion, ITT notes.

It’s a modest start. Still, any solution requires public officials to confront the problem. So far that hasn’t happened. After all, writes columnist Bob Herbert, fixing America’s water system will take a “maturity and vision and effort and sacrifice” that many public officials seem to lack at the present time when it comes to infrastructure. Point in case, says Herbert:

We can’t even build a railroad tunnel beneath the Hudson River from New Jersey to New York.Well played, Bob.

By

CNu

at

November 02, 2010

0

comments

![]()

Labels: contraction , industrial ecosystems

Leaving Labels Aside For A Moment - Netanyahu's Reality Is A Moral Abomination

This video will be watched in schools and Universities for generations to come, when people will ask the question: did we know what was real...

-

theatlantic | The Ku Klux Klan, Ronald Reagan, and, for most of its history, the NRA all worked to control guns. The Founding Fathers...

-

Video - John Marco Allegro in an interview with Van Kooten & De Bie. TSMATC | Describing the growth of the mushroom ( boletos), P...

-

Farmer Scrub | We've just completed one full year of weighing and recording everything we harvest from the yard. I've uploaded a s...