Tuesday, June 03, 2014

internet addiction?

By

CNu

at

June 03, 2014

0

comments

![]()

Labels: addiction , dopamine , helplessness

Friday, January 24, 2014

organic negativity is not false, it's just weaker than consumerism and dopamine hegemony

The Christian rituals of Christmas, then, have been remanufactured by capital and the state during WWII and the Cold War into “Xmas”. Without it, the rituals of life in consumer society might disintegrate even more than they have already, making Xmas an essential aspect of exchange. It mediates the forms of subjectivity in the intimate sphere of caring with corporate agendas of spending and having. Christmas as “Xmas” becomes in film the essential simulation of settled social traditions, family unity, and collective purpose for many modern American Pottersvilles that otherwise lack these qualities.

For Luke, as in It’s A Wonderful Life, such stories are a New Deal fantasy dealt out by corporations and one side, and the state seen as benevolent protector on the other through the medium of bureaucracy – Clarence the angel attempting to get his wing is after all part of a bureaucracy of angels much like the New Deal state.

By

CNu

at

January 24, 2014

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Cathedral , conspicuous consumption , dopamine , global system of 1% supremacy , hegemony , Livestock Management

Wednesday, December 04, 2013

god, dopamine, 3-dimensional space...,

|

| What are God and Heaven doing up in the clouds? |

By

CNu

at

December 04, 2013

4

comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine , hegemony , Race and Ethnicity , the wattles , What IT DO Shawty...

dopamine hegemony depends on the wattles...,

By

CNu

at

December 04, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine , hegemony , Livestock Management , the wattles , What IT DO Shawty...

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

if a path exists toward a moral economy, we're not on it...,

By

CNu

at

September 25, 2013

47

comments

![]()

Labels: banksterism , dopamine , global system of 1% supremacy , hegemony , killer-ape , resource war

Tuesday, August 27, 2013

fixing old markets with new markets the origins and practice of neoliberalism...,

[O]ur own guiding heuristic has been that Neoliberalism has not existed in the past as a settled or fixed state, but is better understood as a transnational movement requiring time and substantial effort in order to attain the modicum of coherence and power it has achieved today. It was not a conspiracy; rather, it was an intricately structured long-term philosophical and political project, or in our terminology, a “thought collective”.

By

CNu

at

August 27, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine , global system of 1% supremacy , hegemony

Wednesday, April 17, 2013

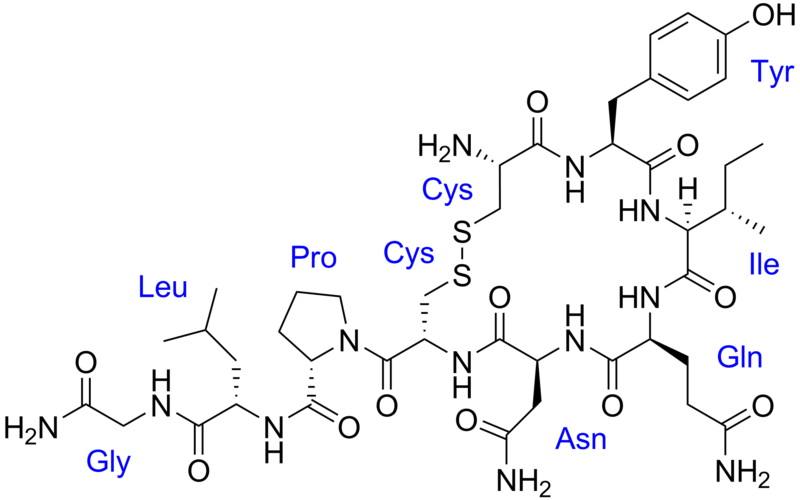

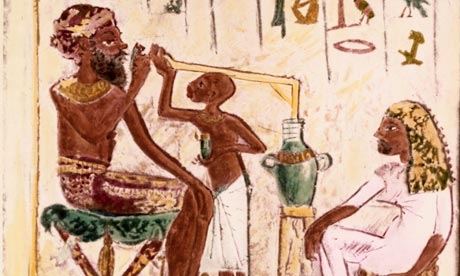

nutrient-shaped, nutrient-seeking, macro-molecular machines...,

|

| the beer of yesteryear..., |

By

CNu

at

April 17, 2013

1 comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine , evolution , food-powered , hegemony

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

review: the moral molecule, source of love and prosperity

By

CNu

at

March 26, 2013

1 comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine , ethology , hegemony , killer-ape

Saturday, December 08, 2012

dopamine: not about pleasure anymore...,

By

CNu

at

December 08, 2012

9

comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine , hegemony , What IT DO Shawty...

pervitin

By

CNu

at

December 08, 2012

1 comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine , hegemony , History's Mysteries

Saturday, November 24, 2012

sprawling from grace...,

By

CNu

at

November 24, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine , hegemony , unintended consequences

Saturday, October 20, 2012

seoul flaunts the come up...,

By

CNu

at

October 20, 2012

5

comments

![]()

Labels: conspicuous consumption , dopamine , hegemony

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

unprecedented freedom to pursue dopamine hits...,

It is, perhaps, the greatest failure of collective leadership since the first world war. The Earth’s living systems are collapsing, and the leaders of some of the most powerful nations – the US, the UK, Germany, Russia – could not even be bothered to turn up and discuss it. Those who did attend the Earth summit last week solemnly agreed to keep stoking the destructive fires: sixteen times in their text they pledged to pursue “sustained growth”, the primary cause of the biosphere’s losses(1).

The efforts of governments are concentrated not on defending the living Earth from destruction, but on defending the machine that is destroying it. Whenever consumer capitalism becomes snarled up by its own contradictions, governments scramble to mend the machine, to ensure – though it consumes the conditions that sustain our lives – that it runs faster than ever before.

The thought that it might be the wrong machine, pursuing the wrong task, cannot even be voiced in mainstream politics. The machine greatly enriches the economic elite, while insulating the political elite from the mass movements it might otherwise confront. We have our bread; now we are wandering, in spellbound reverie, among the circuses.

We have used our unprecedented freedoms, secured at such cost by our forebears, not to agitate for justice, for redistribution, for the defence of our common interests, but to pursue the dopamine hits triggered by the purchase of products we do not need. The world’s most inventive minds are deployed not to improve the lot of humankind but to devise ever more effective means of stimulation, to counteract the diminishing satisfactions of consumption. The mutual dependencies of consumer capitalism ensure that we all unwittingly conspire in the trashing of what may be the only living planet. The failure at Rio de Janeiro belongs to us all.

By

CNu

at

June 27, 2012

1 comments

![]()

Monday, June 18, 2012

like baboons, our elected leaders are literally addicted to power...,

Telegraph | Democracy, the separation of judicial powers and the free press all evolved for essentially one purpose – to reduce the chance of leaders becoming power addicts. Power changes the brain triggering increased testosterone in both men and women. Testosterone and one of its by-products called 3-androstanediol, are addictive, largely because they increase dopamine in a part of the brain’s reward system called the nucleus accumbens. Cocaine has its effects through this system also, and by hijacking our brain’s reward system, it can give short-term extreme pleasure but leads to long-term addiction, with all that that entails.

Telegraph | Democracy, the separation of judicial powers and the free press all evolved for essentially one purpose – to reduce the chance of leaders becoming power addicts. Power changes the brain triggering increased testosterone in both men and women. Testosterone and one of its by-products called 3-androstanediol, are addictive, largely because they increase dopamine in a part of the brain’s reward system called the nucleus accumbens. Cocaine has its effects through this system also, and by hijacking our brain’s reward system, it can give short-term extreme pleasure but leads to long-term addiction, with all that that entails.Unfettered power has almost identical effects, but in the light of yesterday’s Leveson Inquiry interchanges in London, there seems to be less chance of British government ministers becoming addicted to power. Why? Because, as it appears from the emails released by James Murdoch yesterday, they appeared to be submissive to the all-powerful Murdoch empire, hugely dependent on the support of this organization for their jobs and status, who could swing hundreds of thousands of votes for or against them.

Submissiveness and dominance have their effects on the same reward circuits of the brain as power and cocaine. Baboons low down in the dominance hierarchy have lower levels of dopamine in key brain areas, but if they get ‘promoted’ to a higher position, then dopamine rises accordingly. This makes them more aggressive and sexually active, and in humans similar changes happen when people are given power. What’s more, power also makes people smarter, because dopamine improves the functioning of the brain’s frontal lobes. Conversely, demotion in a hierarchy decreases dopamine levels, increases stress and reduces cognitive function.

But too much power - and hence too much dopamine - can disrupt normal cognition and emotion, leading to gross errors of judgment and imperviousness to risk, not to mention huge egocentricity and lack of empathy for others. The Murdoch empire and its acolytes seem to have got carried away by the power they have wielded over the British political system and the unfettered power they have had - unconstrained by any democratic constraints - has led to the quite extraordinary behaviour and arrogance that has been corporately demonstrated.

We should all be grateful that two of the three power-constraining elements of democracy - the legal system and a free press - have managed to at last reign in some of the power of the Murdoch empire. But it was a close call for both, given the threat to financial viability of the newspaper industry and to the integrity of the police system through the close links between the Murdoch empire and Scotland Yard.

By

CNu

at

June 18, 2012

9

comments

![]()

Wednesday, May 09, 2012

dopamine: duality of desire

Many neuroscientists think of the striatal dopamine circuit as a pleasure center. That could explain why addicts have a dopamine spike around the time they get high on drugs. It could also explain the action of drugs like methamphetamine and cocaine, which release and maintain high levels of dopamine and are perceived as profoundly pleasurable.

But a new approach to dopamine has surfaced, partly through the neuroscience of addiction. University of Michigan neuroscientist Kent Berridge and his colleagues view striatal circuitry as the locus of two separate functions: liking and wanting. Their research demonstrates that liking—pleasure—is mediated by opioids. But wanting is mediated by dopamine. The feeling of desire, or wanting, evolved to get us to pursue the things that make us feel good. But the pursuit itself isn’t fun.

According to Berridge, dopamine levels peak when goals are just out of reach and drop once they’ve been attained. For addicts, dopamine increases sensitivity to drug-related cues and generates a state of pursuit. This reconceptualization could explain the findings of neuroscientist Robert Risinger and colleagues who showed that dopamine peaked in the striatum just before, not after, addicts pressed a button that delivered cocaine (NeuroImage, 26: 1097-1108, 2005). And those same addicts reported “craving”—not “high”—as the experiential correlate of dopamine.

So why do meth and coke feel so good and not just like souped-up craving? Attraction to something you don’t have access to isn’t fun. When I was in the throes of intense psychological addiction, my thoughts were continuously (and unpleasantly) drawn to drug imagery. It would be so great to have some now! How can I get some tonight?! But attraction to something you are just about to get feels marvelous. Dopamine-induced engagement turns into a headlong rush of triumph when the goal is finally accessible.

This perspective on the dual nature of attraction helps make sense of addiction. Unsated attraction can be a kind of torture, and addicts may seek drugs to put an end to that torture, more than for the modicum of pleasure drugs actually bestow.

Advances in neuroscience encourage fresh insights, not only into addiction, but into the wider domains of emotion and personality development. Yet a synthesis between neuroscience and subjectivity can perhaps teach us more than either one alone.

By

CNu

at

May 09, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine

Tuesday, May 01, 2012

prohibition costs billions, legalization would earn billions - but what about its effect on dopamine hegemony?

Miron predicts that legalizing marijuana would save $7.7 billion per year in government expenditure on enforcement, in addition to generating $2.4 billion annually if taxed like most consumer goods, or $6 billion per year if taxed similarly to alcohol and tobacco. The economists signing the petition note that the budgetary implications of marijuana prohibition are just one of many factors to be considered, but declare it essential that these findings become a serious part of the national decriminalization discussion.

The advantages of marijuana legalization extend far beyond an opportunity to make a dent in our federal deficit. The criminalization of marijuana is one of the many fights in the War on Drugs that has failed miserably. And while it's tempting to associate only the harder, "scarier" drugs with this botched crusade, the fact remains that marijuana prohibition is very much a part of the battle. The federal government has even classified marijuana as a Schedule 1 substance (its most serious category of substances), placing it in a more dangerous category than cocaine. More than 800,000 people are arrested for marijuana use and possession each year, and 46 percent of all drug prosecutions across the country are for marijuana possession. Yet this costly and time-consuming targeting of marijuana users by law enforcement and lawmakers has done little to quell use of the drug.

The criminalization of marijuana has not only resulted in a startlingly high number of arrests, it also reflects the devastating disparate racial impact of the War on Drugs. Despite ample evidence that marijuana is used more frequently by white people, Blacks and Latinos account for a grossly disproportionate percentage of the 800,000 people arrested annually for marijuana use and possession. These convictions hinder one's ability to find or keep employment, vote or gain access to affordable housing. The fact that these hard-to-shake consequences – bad enough as they are — are suffered more frequently by a demographic that uses marijuana less makes our current policies toward marijuana all the more unfair, unwise and unacceptable.

By

CNu

at

May 01, 2012

8

comments

![]()

Labels: agenda , dopamine , elite , establishment , hegemony

Sunday, April 29, 2012

with the dopamine flowing like this, you knew the booty popping couldn't be far behind...,

"I would definitely be interested if the price was right," says Wang Xizhen as he ogled a deep purple Aston Martin DBS.

Aston Martin launched its Dragon 88 China-only limited edition this week. With gold dragon emblems embroidered onto its leather seats, the car also carries a hefty price tag - more than 5 million yuan (nearly $800,000).

Jeep also launched a China-inspired car -- a flashy Wrangler concept car emblazoned with a long silvery dragon across the hood.

"Jeep brand sales in China in 2011 increased 81% over the prior year and China," said Mike Manley, CEO of Jeep Brand, Chrysler group, at the unveiling on Monday. "Last year, more Jeep vehicles were sold in China than in any other country besides the U.S. and Canada."

Manley said because the brand is committed to China, it's important to design and tailor vehicles specifically to Chinese tastes. But some consumers, like Wang, disagreed.

"Just because it has a dragon on it, doesn't mean Chinese people will love it. After all, we're after going after a western brand," said Wang. "I like the subtlety of Aston Martin's dragon design, but to put a huge dragon across the entire car is going overboard."

Jeep and Aston Martin are among many foreign automakers hoping to woo hundreds of thousands of Chinese consumers visiting the show this week, especially as China has become the world's largest auto market amid a sales slump in Europe and tepid growth in the United States.

Despite the push in green cars in previous years following government subsidies for cleaner vehicles, this year's focus turned to gas-guzzling SUVs. Crowds swooned over the new Lamborghini Urus SUV concept car -- a potential competitor to the popular Porsche Cayenne.

Ford also unveiled three SUVs at the show, including the EcoSport, which is expected to be manufactured at the company's China factory in Chongqing.

"SUVs are a strength for Ford globally and here in China, the SUV segment is one of the fastest growing segments in the industry," said Joe Hinrichs, president of Ford's Asia Pacific and Africa region. "So you put the two together...it's a very exciting time."

Automakers have turned their attention to bigger cars and flashier cars to attract consumers since there are fewer government-backed incentives to pursue green technology, analysts say.

By

CNu

at

April 29, 2012

6

comments

![]()

Labels: dopamine , hegemony , What IT DO Shawty...

Tuesday, April 03, 2012

#revolutionwhatrevolution?

FT | When I recently discovered Twitter, I went from contemptuous to addicted in about three days. But one thing still puzzles me about the world’s 10th most popular website: the notion that it’s a revolutionary medium. The failed Moldovan rebellion of 2009 was probably the first to be dubbed the “Twitter revolution”, but since then, Twitter has been credited with launching the Iranian uprising, Arab spring and London riots. Now it has supposedly prompted the African Union to hunt for the Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony, after an anti-Kony propaganda film spread through social media and was watched more than 100 million times. I confidently predict that the next revolution anywhere on earth will be dubbed “the Twitter revolution”.

FT | When I recently discovered Twitter, I went from contemptuous to addicted in about three days. But one thing still puzzles me about the world’s 10th most popular website: the notion that it’s a revolutionary medium. The failed Moldovan rebellion of 2009 was probably the first to be dubbed the “Twitter revolution”, but since then, Twitter has been credited with launching the Iranian uprising, Arab spring and London riots. Now it has supposedly prompted the African Union to hunt for the Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony, after an anti-Kony propaganda film spread through social media and was watched more than 100 million times. I confidently predict that the next revolution anywhere on earth will be dubbed “the Twitter revolution”. Non-tweeting readers may have formed the impression that the Twittersphere is devoted to summoning people to demonstrations in grey repressive capitals. In fact, “trending” items are usually celebrity deaths, goals in football matches or anything to do with the teenaged singer Justin Bieber. And what’s true of Twitter appears true of computers in general. They are antirevolutionary devices. The global addiction to computers is helping keep the world quiet and peaceful.

Every now and then, of course, social media do contribute to change. The Facebook page “We are all Khaled Said”, named after a young Egyptian who died in police custody, helped galvanise protesters in Cairo’s Tahrir Square last year. And bad activists use YouTube and Twitter too. “On the web one can proselytise for the jihad all day and night with friends from around the world,” writes Jytte Klausen, an expert on terrorism at Brandeis University, and colleagues.

Mostly, though, computers produce quietism. Despite Occupy Wall Street, a striking fact of the great recession in developed countries has been the passivity of young people.

By

CNu

at

April 03, 2012

7

comments

![]()

Thursday, September 29, 2011

the rat race for prestige

By

CNu

at

September 29, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

addiction is not a disease of the brain?

NPR | Addiction has been moralized, medicalized, politicized, and criminalized. And, of course, many of us are addicts, have been addicts or have been close to addicts. Addiction runs very hot as a theme.

NPR | Addiction has been moralized, medicalized, politicized, and criminalized. And, of course, many of us are addicts, have been addicts or have been close to addicts. Addiction runs very hot as a theme.Part of what makes addiction so compelling is that it forms a kind of conceptual/political crossroads for thinking about human nature. After all, to make sense of addiction we need to make sense of what it is to be an agent who acts, with values, in the face of consequences, under pressure, with compulsion, out of need and desire. One needs a whole philosophy to understand addiction.

Today I want to respond to readers who were outraged by my willingness even to question whether addiction is a disease of the brain.

Let us first ask: what makes something — a substance or an activity — addictive? Is there a property shared by all the things to which we can get addicted?

Unlikely. Addictive substances such as alcohol, heroin and nicotine are chemically distinct. Moreover, activities such as gambling, eating, sex — activities that are widely believed to be addictive — have no ingredients.

And yet it is remarkable — as Gene Heyman notes in his excellent book on addiction — that there are only 20 or so distinct activities and substances that produce addiction. There must be something in virtue of which these things, and these things alone, give rise to the distinctive pattern of use and abuse in the face of the medical, personal and legal perils that we know can stem from addiction.

What do gambling, sex, heroin and cocaine — and the other things that can addict us — have in common?

One strategy is to look not to the substances and activities themselves, but to the effects that they produce in addicts. And here neuroscience has delivered important insights.

If you feed an electrical wire through a rat's skull and onto to a short dopamine release circuit that connects the VTA (ventral tegmental area) and the nucleus accumbens, and if you attach that wire to a lever-press, the rat will self-stimulate — press the lever to produce the increase in dopamine — and it will do so basically foreover, forgoing food, sex, water and exercise. Addiction, it would seem, is produced by direct action on the brain!

(See here for a useful Wikipedia review of this literature.)

And indeed, there is now a substantial body of evidence supporting the claim that all drugs or activities of abuse (as we can call them), have precisely this kind of effect on this dopamine neurochemical circuit.

When the American Society of Addiction Medicine recently declared addiction to be a brain disease their conclusion was based on findings like this. Addiction is an effect brought about in a neurochemical circuit in the brain. If true, this is important, for it means that if you want to treat addiction, you need to find ways to act on this neural substrate.

By

CNu

at

September 13, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Elite Donor Level Conflicts Openly Waged On The National Political Stage

thehill | House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith (R-Mo.) has demanded the U.S. Chamber of Commerce answer questions about th...

-

theatlantic | The Ku Klux Klan, Ronald Reagan, and, for most of its history, the NRA all worked to control guns. The Founding Fathers...

-

Video - John Marco Allegro in an interview with Van Kooten & De Bie. TSMATC | Describing the growth of the mushroom ( boletos), P...

-

Farmer Scrub | We've just completed one full year of weighing and recording everything we harvest from the yard. I've uploaded a s...