Thursday, January 05, 2012

Online K-12 Schooling in the U.S.

By

CNu

at

January 05, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Labels: change , paradigm , The Hardline

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

six reasons young christians leave church

The research project was comprised of eight national studies, including interviews with teenagers, young adults, parents, youth pastors, and senior pastors. The study of young adults focused on those who were regular churchgoers Christian church during their teen years and explored their reasons for disconnection from church life after age 15.

No single reason dominated the break-up between church and young adults. Instead, a variety of reasons emerged. Overall, the research uncovered six significant themes why nearly three out of every five young Christians (59%) disconnect either permanently or for an extended period of time from church life after age 15.

Reason #1 – Churches seem overprotective.

A few of the defining characteristics of today's teens and young adults are their unprecedented access to ideas and worldviews as well as their prodigious consumption of popular culture. As Christians, they express the desire for their faith in Christ to connect to the world they live in. However, much of their experience of Christianity feels stifling, fear-based and risk-averse. One-quarter of 18- to 29-year-olds said “Christians demonize everything outside of the church” (23% indicated this “completely” or “mostly” describes their experience). Other perceptions in this category include “church ignoring the problems of the real world” (22%) and “my church is too concerned that movies, music, and video games are harmful” (18%).

Reason #2 – Teens’ and twentysomethings’ experience of Christianity is shallow.

A second reason that young people depart church as young adults is that something is lacking in their experience of church. One-third said “church is boring” (31%). One-quarter of these young adults said that “faith is not relevant to my career or interests” (24%) or that “the Bible is not taught clearly or often enough” (23%). Sadly, one-fifth of these young adults who attended a church as a teenager said that “God seems missing from my experience of church” (20%).

Reason #3 – Churches come across as antagonistic to science.

One of the reasons young adults feel disconnected from church or from faith is the tension they feel between Christianity and science. The most common of the perceptions in this arena is “Christians are too confident they know all the answers” (35%). Three out of ten young adults with a Christian background feel that “churches are out of step with the scientific world we live in” (29%). Another one-quarter embrace the perception that “Christianity is anti-science” (25%). And nearly the same proportion (23%) said they have “been turned off by the creation-versus-evolution debate.” Furthermore, the research shows that many science-minded young Christians are struggling to find ways of staying faithful to their beliefs and to their professional calling in science-related industries.

Reason #4 – Young Christians’ church experiences related to sexuality are often simplistic, judgmental.

With unfettered access to digital pornography and immersed in a culture that values hyper-sexuality over wholeness, teen and twentysometing Christians are struggling with how to live meaningful lives in terms of sex and sexuality. One of the significant tensions for many young believers is how to live up to the church's expectations of chastity and sexual purity in this culture, especially as the age of first marriage is now commonly delayed to the late twenties. Research indicates that most young Christians are as sexually active as their non-Christian peers, even though they are more conservative in their attitudes about sexuality. One-sixth of young Christians (17%) said they “have made mistakes and feel judged in church because of them.” The issue of sexuality is particularly salient among 18- to 29-year-old Catholics, among whom two out of five (40%) said the church’s “teachings on sexuality and birth control are out of date.”

Reason #5 – They wrestle with the exclusive nature of Christianity.

Younger Americans have been shaped by a culture that esteems open-mindedness, tolerance and acceptance. Today’s youth and young adults also are the most eclectic generation in American history in terms of race, ethnicity, sexuality, religion, technological tools and sources of authority. Most young adults want to find areas of common ground with each other, sometimes even if that means glossing over real differences. Three out of ten young Christians (29%) said “churches are afraid of the beliefs of other faiths” and an identical proportion felt they are “forced to choose between my faith and my friends.” One-fifth of young adults with a Christian background said “church is like a country club, only for insiders” (22%).

Reason #6 – The church feels unfriendly to those who doubt.

Young adults with Christian experience say the church is not a place that allows them to express doubts. They do not feel safe admitting that sometimes Christianity does not make sense. In addition, many feel that the church’s response to doubt is trivial. Some of the perceptions in this regard include not being able “to ask my most pressing life questions in church” (36%) and having “significant intellectual doubts about my faith” (23%). In a related theme of how churches struggle to help young adults who feel marginalized, about one out of every six young adults with a Christian background said their faith “does not help with depression or other emotional problems” they experience (18%).

By

CNu

at

December 20, 2011

21

comments

![]()

Labels: change , magical thinking , paradigm

Friday, December 16, 2011

effective and sustainable public education for these children will revolutionize all public education

USAToday | One in 45 children in the USA — 1.6 million children — were living on the street, in homeless shelters or motels, or doubled up with other families last year, according to the National Center on Family Homelessness.

USAToday | One in 45 children in the USA — 1.6 million children — were living on the street, in homeless shelters or motels, or doubled up with other families last year, according to the National Center on Family Homelessness.The numbers represent a 33% increase from 2007, when there were 1.2 million homeless children, according to a report the center is releasing Tuesday.

"This is an absurdly high number," says Ellen Bassuk, president of the center. "What we have new in 2010 is the effects of a man-made disaster caused by the economic recession. … We are seeing extreme budget cuts, foreclosures and a lack of affordable housing."

The report paints a bleaker picture than one by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which nonetheless reported a 28% increase in homeless families, from 131,000 in 2007 to 168,000 in 2010.

Dennis Culhane, a University of Pennsylvania professor of social policy, says HUD's numbers are much smaller because they count only families living on the street or in emergency shelters.

"It is a narrower standard of homelessness," he says. However, Culhane says, "the bottom line is we've shown an increase in the percentage of homeless families."

The study, a state-by-state report card, looks at four years' worth of Education Department data. It assesses how homeless children fare based on factors including the state's wages, poverty and foreclosure rates, cost of housing and its programs for homeless families.

The states where homeless children fare the best are Vermont, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota and Maine.

It finds the worst states for homeless children are Southern states where poverty is high, including Alabama, Mississippi and Arkansas, and states decimated by foreclosures and job losses, such as Arizona, California and Nevada.

By

CNu

at

December 16, 2011

20

comments

![]()

Labels: change , micro-insurgencies , paradigm

Wednesday, December 07, 2011

La longue durée

morrisberman | La longue durée is an expression used by the Annales School of French historians to indicate an approach that gives priority to long-term historical structures over short-term events. The phrase was coined by Fernand Braudel in an article he published in 1958. Basically, the Annales historians held that the short-term time-scale is the domain of the chronicler and the journalist, whereas la longue durée concentrates on all-but-permanent or slowly evolving structures. Thus beneath the twists and turns of any economic system, wrote Braudel, which can seem like major changes to the people living through them, lie "old attitudes of thought and action, resistant frameworks dying hard, at times against all logic." An important derivative of the Annales research is the work of the World Systems Analysis school, including Immanuel Wallerstein and Christopher Chase-Dunn, which similarly focuses on long-term structures: capitalism, in particular.

morrisberman | La longue durée is an expression used by the Annales School of French historians to indicate an approach that gives priority to long-term historical structures over short-term events. The phrase was coined by Fernand Braudel in an article he published in 1958. Basically, the Annales historians held that the short-term time-scale is the domain of the chronicler and the journalist, whereas la longue durée concentrates on all-but-permanent or slowly evolving structures. Thus beneath the twists and turns of any economic system, wrote Braudel, which can seem like major changes to the people living through them, lie "old attitudes of thought and action, resistant frameworks dying hard, at times against all logic." An important derivative of the Annales research is the work of the World Systems Analysis school, including Immanuel Wallerstein and Christopher Chase-Dunn, which similarly focuses on long-term structures: capitalism, in particular.The “arc” of capitalism, according to WSA, is about 600 years long, from 1500 to 2100. It is our particular (mis)fortune to be living through the beginning of the end, the disintegration of capitalism as a world system. It was mostly commercial capital in the sixteenth century, evolving into industrial capital in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and then moving on to financial capital—money created by money itself, and by speculation in currency—in the twentieth and twenty-first. In dialectical fashion, it will be the very success of the system that eventually does it in.

The last time a change of this magnitude occurred was during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, during which time the medieval world began to come apart and be replaced by the modern one. In the classic study of the period, The Waning of the Middle Ages, Dutch historian Johan Huizinga depicted the time as one of depression and cultural exhaustion—like our own age, not much fun to live through. One reason for this is that the world is literally perched over an abyss (brilliantly depicted at the end of Shakespeare’s The Tempest). What is on deck, so to speak, is largely unknown, and to have to hover over the unknown for a long time is, to put it colloquially, a bit of a drag. The same thing was true at the time of the collapse of the Roman Empire as well (on the ruins of which the feudal system slowly arose).

I was musing on all of this stuff last week when I happened to run across a remarkable essay by Naomi Klein, “Capitalism vs. the Climate” (The Nation, 28 November 2011). In what appears to be something of a radical shift for her, she chastises the Left for not understanding what the Right does correctly perceive: that the whole climate change debate is a serious threat to capitalism. The Left, she says, wants to soft-pedal the implications; it wants to say that environmental protection is compatible with economic growth, that it is not a threat to capital or labor. It wants to get everyone to buy a hybrid car, for example (which I have personally compared to diet cheesecake), or use more efficient light bulbs, or recycle, as if these things were adequate to the crisis at hand. But the Right is not fooled: it sees Green as a Trojan horse for Red, the attempt “to abolish capitalism and replace it with some kind of eco-socialism.” It believes—correctly—that the politics of global warming is inevitably an attack on the American Dream, on the whole capitalist structure. Thus Larry Bell, in Climate of Corruption, argues that environmental politics is essentially about “transforming the American way of life in the interests of global wealth distribution”; and British blogger James Delinpole notes that “Modern environmentalism successfully advances many of the causes dear to the left: redistribution of wealth, higher taxes, greater government intervention, [and] regulation.”

What Naomi is saying to the Left, in effect, is: Why fight it? These nervous nellies on the Right are—right! Those of us on the Left can’t keep talking about compatibility of limits-to-growth and unrestrained greed, or claiming that climate action is “just one issue on a laundry list of worthy causes vying for progressive attention,” or urging everyone to buy a Prius. Folks like Thomas Friedman or Al Gore, who “assure us that we can avert catastrophe by buying ‘green’ products and creating clever markets in pollution”—corporate green capitalism, in a word—are simply living in denial. “The real solutions to the climate crisis,” she writes, “are also our best hope of building a much more enlightened economic system—one that closes deep inequalities, strengthens and transforms the public sphere, generates plentiful, dignified work, and radically reins in corporate power.”

In one of the essays in A Question of Values (“conspiracy vs. Conspiracy in American History”), I lay out some of the “unconscious programs” buried in the American psyche from our earliest days, programs that account for most of our so-called conscious behavior. These include the notion of an endless frontier—a world without limits—and the ideal of extreme individualism—you do not need, and should not need, anyone’s help to “make it” in the world. Combined, the two of these provide a formula for enormous capitalist power and inevitable capitalist collapse (hence, the dialectical dimension of it all). Of this, Naomi writes:

“The expansionist, extractive mindset, which has so long governed our relationship to nature, is what the climate crisis calls into question so fundamentally. The abundance of scientific research showing we have pushed nature beyond its limits does not just demand green products and market-based solutions; it demands a new civilizational paradigm, one grounded not in dominance over nature but in respect for natural cycles of renewal—and acutely sensitive to natural limits....These are profoundly challenging revelations for all of us raised on Enlightenment ideals of progress.” (This is exactly what I argued in The Reenchantment of the World; nice to see it all coming around again.) “Real climate solutions,” she continues, “are ones that steer [government] interventions to systematically disperse and devolve power and control to the community level, through community-controlled renewable energy, local organic agriculture or transit systems genuinely accountable to their users.” Hence, she concludes, the powers that be have reason to be afraid, and to deny the data on global warming, for what is really required at this point is the end of the free-market ideology. And, I would add, the end of the arc of capitalism referred to above. It’s going to be (is) a colossal fight, not only because the powers that be want to hang on to their power, but because the arc and all its ramifications have given their class Meaning with a capital M for 500+ years. This is what the OWS protesters need to tell the 1%: Your lives are a mistake. This is what “a new civilizational paradigm” finally means.

By

CNu

at

December 07, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Sunday, November 13, 2011

how I stopped worrying and learned to love the OWS protests

Get More: Colbert Report Full Episodes,Political Humor & Satire Blog,Video Archive

By

CNu

at

November 13, 2011

19

comments

![]()

Labels: change , open source culture , paradigm

Wednesday, October 05, 2011

occupy wall street picks up some academic hitchhikers...,

Video - Amy Goodman talks with Cornel West about Occupy Wall St.

One reason is their sheer size and persistence—it’s a rare street demonstration that is still gaining steam after almost three weeks. Another is the entry of media-savvy organized labor groups, with Reuters reporting that major unions representing state and city workers, nurses, communication workers and transit workers were set to take part in a march through Manhattan’s Financial District on Wednesday afternoon. Students, too, are participating en masse, with walkouts planned at some 75 universities across the country. And, of course, several of the usual-suspect celebrities have joined the cause.

A more interesting development, and perhaps an overlooked reason why news outlets have begun to treat the protesters as something more than “aggrieved youth,” is the growing involvement of some of the country’s best-known public intellectuals, who have begun to articulate what they see as the main goal of a movement whose aims so far have been vague: stronger financial reform.

An early backer from academia was Princeton professor Cornel West, who applauded the protesters for fighting “the greed of Wall Street oligarchs and corporate plutocrats who squeeze the democratic juices out of this country.” He was out on the streets of Boston Wednesday with the marchers, according to the Boston Herald.

While West has a reputation as an activist, the movement has more recently begun to draw in professors of a less demonstrative bent as well. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University gave the New York protests a lift on Sunday with a speech that has been making the rounds via Youtube. Because the protesters were prohibited from using a megaphone, he paused in between lines for the crowd that had gathered around him to repeat his words more loudly. He told the protesters they were doing the right thing by standing up to Wall Street:

You are right to be indignant. The fact is the system is not working right. It is not right that we have so many people without jobs when we have so many needs that we have to fulfill. It’s not right that we are throwing people out of their houses when we have so many homeless people.Stiglitz and West have been joined by Lawrence Lessig, the renowned Harvard law professor, who took to Twitter on Tuesday to urge his followers to join the protests, then wrote in support of them on the Huffington Post on Wednesday, comparing them to the Arab Spring:

Our financial markets have an important role to play. They’re supposed to allocate capital, manage risks. But they misallocated capital, and they created risk. We are bearing the cost of their misdeeds. There’s a system where we’ve socialized losses and privatized gains. That’s not capitalism; that’s not a market economy. That’s a distorted economy, and if we continue with that, we won’t succeed in growing, and we won't succeed in creating a just society.

The arrest of hundreds of tired and unwashed kids, denied the freedom of a bullhorn, and the right to protest on public streets, may well be the first real green-shoots of this, the American spring. And if nurtured right, it could well begin real change.

By

CNu

at

October 05, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Labels: change , cognitive infiltration , narrative

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

why you should root for colleges to go online

By

CNu

at

September 28, 2011

2

comments

![]()

Labels: change , Collapse Casualties , paradigm

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Friday, September 09, 2011

are jobs obsolete?

CNN | Jobs, as such, are a relatively new concept. People may have always worked, but until the advent of the corporation in the early Renaissance, most people just worked for themselves. They made shoes, plucked chickens, or created value in some way for other people, who then traded or paid for those goods and services. By the late Middle Ages, most of Europe was thriving under this arrangement.

CNN | Jobs, as such, are a relatively new concept. People may have always worked, but until the advent of the corporation in the early Renaissance, most people just worked for themselves. They made shoes, plucked chickens, or created value in some way for other people, who then traded or paid for those goods and services. By the late Middle Ages, most of Europe was thriving under this arrangement.The only ones losing wealth were the aristocracy, who depended on their titles to extract money from those who worked. And so they invented the chartered monopoly. By law, small businesses in most major industries were shut down and people had to work for officially sanctioned corporations instead. From then on, for most of us, working came to mean getting a "job."

The Industrial Age was largely about making those jobs as menial and unskilled as possible. Technologies such as the assembly line were less important for making production faster than for making it cheaper, and laborers more replaceable. Now that we're in the digital age, we're using technology the same way: to increase efficiency, lay off more people, and increase corporate profits.

While this is certainly bad for workers and unions, I have to wonder just how truly bad is it for people. Isn't this what all this technology was for in the first place? The question we have to begin to ask ourselves is not how do we employ all the people who are rendered obsolete by technology, but how can we organize a society around something other than employment? Might the spirit of enterprise we currently associate with "career" be shifted to something entirely more collaborative, purposeful, and even meaningful?

Instead, we are attempting to use the logic of a scarce marketplace to negotiate things that are actually in abundance. What we lack is not employment, but a way of fairly distributing the bounty we have generated through our technologies, and a way of creating meaning in a world that has already produced far too much stuff.

The communist answer to this question was just to distribute everything evenly. But that sapped motivation and never quite worked as advertised. The opposite, libertarian answer (and the way we seem to be going right now) would be to let those who can't capitalize on the bounty simply suffer. Cut social services along with their jobs, and hope they fade into the distance.

But there might still be another possibility -- something we couldn't really imagine for ourselves until the digital era. As a pioneer of virtual reality, Jaron Lanier, recently pointed out, we no longer need to make stuff in order to make money. We can instead exchange information-based products.

We start by accepting that food and shelter are basic human rights. The work we do -- the value we create -- is for the rest of what we want: the stuff that makes life fun, meaningful, and purposeful.

This sort of work isn't so much employment as it is creative activity. Unlike Industrial Age employment, digital production can be done from the home, independently, and even in a peer-to-peer fashion without going through big corporations. We can make games for each other, write books, solve problems, educate and inspire one another -- all through bits instead of stuff. And we can pay one another using the same money we use to buy real stuff.

For the time being, as we contend with what appears to be a global economic slowdown by destroying food and demolishing homes, we might want to stop thinking about jobs as the main aspect of our lives that we want to save. They may be a means, but they are not the ends.

By

CNu

at

September 09, 2011

6

comments

![]()

Labels: change , paradigm , Possibilities

Wednesday, September 07, 2011

the radical implications of a zero growth economy

Video - Maurice Strong Interview (BBC, 1972)

The argument in this paper is that the implications of a steady-state economy have not been understood at all well, especially by its advocates. Most proceed as if we can and should eliminate the growth element of the present economy while leaving the rest more or less as it is. It will be argued firstly that this is not possible, because this is not an economy which has growth; it is a growth-economy, a system in which most of the core structures and processes involve growth. If growth is eliminated then radically different ways of carrying out many fundamental processes will have to be found. Secondly, the critics of growth typically proceed as if it is the only or the primary or the sufficient thing that has to be fixed, but it will be argued that the major global problems facing us cannot be solved unless several fundamental systems and structures within consumer-capitalist society are radically remade. What is required is much greater social change than Western society has undergone in several hundred years.

Before offering support for these claims it is important to sketch the general “limits to growth” situation confronting us. The magnitude and seriousness of the global resource and environmental problem is not generally appreciated. Only when this is grasped is it possible to understand that the social changes required must be huge, radical and far reaching. The initial claim being argued here (and detailed in Trainer 2010b) is that consumer-capitalist society cannot be reformed or fixed; it has to be largely scrapped and remade along quite different lines.

The “limits to growth” case: An outline

The planet is now racing into many massive problems, any one of which could bring about the collapse of civilization before long. The most serious are the destruction of the environment, the deprivation of the Third World, resource depletion, conflict and war, and the breakdown of social cohesion. The main cause of all these problems is over-production and over-consumption – people are trying to live at levels of affluence that are far too high to be sustained or for all to share.

Our society is grossly unsustainable – the levels of consumption, resource use and ecological impact we have in rich countries like Australia are far beyond levels that could be kept up for long or extended to all people. Yet almost everyone’s supreme goal is to increase material living standards and the GDP and production and consumption, investment, trade, etc., as fast as possible and without any limit in sight. There is no element in our suicidal condition that is more important than this mindless obsession with accelerating the main factor causing the condition.

The following points drive home the magnitude of the overshoot.

By

CNu

at

September 07, 2011

10

comments

![]()

Labels: change , contraction , paradigm

Saturday, June 11, 2011

arnach tugs big don's sleeve

How We Decide by Jonah LehrerIf you believe that there is meaning in the tone and manner in which words are said and stories told, then you have a compelling reason to listen to the audiobook recording of that last one as read by the author. In any case, you should have no problem getting through any of these books if you are able to read and comprehend at the high school level; there's nothing obscure or technical anywhere in any of them. What you may find, in fact, is that you are drawn into each as you might be by a good novel. You might also find yourself looking forward to reading (or listening to) them again, because you know you’ll get a little something more out of each the next time through.

Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely

What the Dog Saw by Malcolm Gladwell

My Stroke of Insight by Jill Bolte Taylor

I believe that, if you are able to understand and integrate the information in these books into your thinking, you will discover that you have a better understanding of, and better control over, how your own brain works and how your mind is affected by things that are presented to you in everyday life. Besides, what’s the most it’ll cost you? A little lazy time and a trip or two to the library? As you can see from the wikipedia page in the title link, you can read Gladwell’s book starting right now, for free, from his website!

The question, Big Don, is whether or not you’re actually man enough to do it? I can see from your bookshelf that you are not a man afraid of words. A whole summer should be enough time. Now, I have a feeling that the suggestion alone (particularly coming here on this blog) is likely to predispose you against both the action and the material. If so, that would be a shame. Particularly because, since you and I come from similar technical backgrounds (I think I might need to get myself a copy of Carrier’s fan book you got that ~1970 edition of on your bottom shelf there), I’m very interested to learn when the setting of one’s ways in stone will occur and when to expect to reach the point at which all new information becomes irrelevant (or perhaps worse, dangerous). I thought engineers were different than that. Not that I believe any of that is actually inevitable…just (unfortunately) common.

By

CNu

at

June 11, 2011

7

comments

![]()

Labels: change , co-evolution , hope , work

Thursday, June 02, 2011

bitcoin vs. central bankers

BitcoinNews | Max interviews guest Jon Matonis who introduces Bitcoin to the RT audience.

“Overall though, I do think the exchangers are the weakest link in the chain”.

“On the government level I think what this is going to actually lead to is a move and a shift away from the model of taxing income and I think you’re going to start to see governments move towards some type of consumption-based tax or headcount-type tax and the reason is because the income levels of individuals are going to become more and more difficult to ascertain”

“I believe digital cash will do to legal tender what BitTorrents did to copyrights”. Fist tap Dale.

By

CNu

at

June 02, 2011

16

comments

![]()

Labels: change , paradigm , Possibilities

Wednesday, June 01, 2011

leading world politicians urge 'paradigm shift' on drugs policy

Guardian | Former presidents, prime ministers, eminent economists and leading members of the business community will unite behind a call for a shift in global drug policy. The Global Commission on Drug Policy will host a press conference at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York to launch a report that describes the drug war as a failure and calls for a "paradigm shift" in approaching the issue.

Guardian | Former presidents, prime ministers, eminent economists and leading members of the business community will unite behind a call for a shift in global drug policy. The Global Commission on Drug Policy will host a press conference at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York to launch a report that describes the drug war as a failure and calls for a "paradigm shift" in approaching the issue.Those backing the call include Ernesto Zedillo, former president of Mexico; George Papandreou, former prime minister of Greece; César Gaviria, former president of Colombia; Kofi Annan, former UN secretary general; Fernando Henrique Cardoso, former president of Brazil; George Shultz, former US secretary of state; Javier Solana, former EU high representative; Virgin tycoon Richard Branson; and Paul Volcker, former chairman of the US Federal Reserve.

The commission will call for drug policy to move from being focused on criminal justice towards a public health approach. The global advocacy organisation Avaaz, which has nine million members, will present a petition in support of the commission's recommendations to UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon.

The commission is the most distinguished group to call for such far-reaching changes in the way society deals with illicit drugs. Danny Kushlick, head of external affairs at Transform, the drug policy foundation that has consultative status with the UN, said current events, such as the cartel-related violence in Mexico, President Barack Obama's comments that it was "perfectly legitimate" to question whether the war on drugs was working, and the wider global economic crisis, had given calls for a comprehensive overhaul of the world's drugs policy a fresh impetus.

By

CNu

at

June 01, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Labels: change , elite , establishment , paradigm

Sunday, May 15, 2011

the fukushima plate

Fukushima Plate - In a society that sacrifices reason to profit, security becomes a luxury for those who can afford it.

Fukushima Plate - In a society that sacrifices reason to profit, security becomes a luxury for those who can afford it.The Fukushima Plate is an ordinary kitchen plate with built-in radioactive meter to visualize your food's level of contamination. It might become an indespensable tool of survival in the future. Fist tap Dale.

By

CNu

at

May 15, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Thursday, March 10, 2011

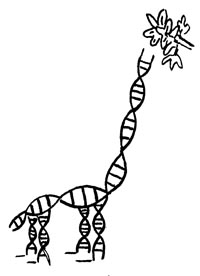

epigenetics and society

The Scientist | The potent wish in the productive hour

The Scientist | The potent wish in the productive hourCalls to its aid Imagination’s power,

O’er embryon throngs with mystic charm presides,

And sex from sex the nascent world divides…

—Erasmus Darwin,

“The Temple of Nature,” Canto II

I was first introduced to Charles Darwin’s flamboyant grandfather when I was an undergraduate searching through Michigan State’s wonderful Special Collections. In between bothering the curators for archived copies of Howard the Duck, I read Erasmus’s prose and poetry, and was treated to a great mind grappling with ideas that presaged one of the truly great ideas of modern times, the theory of evolution. As the passage above hints, Erasmus believed that environmental influences, in particular the “Imagination” of the parents, greatly influenced the phenotype of the child.

How very pre-Victorian (and post-). Erasmus anticipated Charles in many ways, but surprising results in the field of epigenetics—heritable (and reversible) changes in gene expression—suggest that he may have been very far ahead of his time indeed. In the current issue, David Berreby cites the increasing body of work that correlates childhood trauma with DNA methylation with suicide. One’s personal epigenome is modified by environmental perturbations, and that influences behavior. Certainly the Victorians could have related to the notion of an Original Sin that made its heritable mark on the genomes of parents created innocent, passing the curse down to their descendants. That said, the Victorians did have their biases, and it was of course the father who had the predominant influence over the child. But recently published studies of genetic imprinting show that the two parents’ influence on their offspring is more akin to a tug of war.

The Lamarckian idea that giraffes’ reaching for leaves resulted in longer-necked progeny seems silly to us today, primarily because we know so very much about the underlying mechanisms of genetics. And yet Lamarck may have a last laugh—think inheritance patterns in ciliates, or the effect of diet on the coat color of agouti mouse offspring. We are in the midst of a paradigm shift in our understanding of how evolution can act…on evolution, yielding mechanisms that allow both adaptation and heritability within the course of a lifetime. And such paradigm shifts almost always have societal consequences. Manel Esteller shows that epigenetics also impacts the “dark genome” in a way that may improve cancer diagnostics. An even more far-reaching consequence is that it may prove possible to engineer epigenetics, as Bob Kingston’s Thought Experiment tacitly suggests. If so, will epigenetic engineering be subject to the same restrictions as genetic engineering? Or will this be a way that we can not merely treat disease, but possibly engineer human health into future generations?

Andrzej Krauze

Such possibilities will be the rational outcome of a great deal of research and debate that is yet to come. However, there are at least two outcomes of the revolution in progress that would seem to have more near-term consequences. First, the overturning of a purely Darwinian paradigm will undoubtedly be viewed as the overturning of Darwin and his Theory itself. It matters not a whit that science will have been shown, once again, to be self-correcting, and to provide a means of advancing knowledge through the application of the experimental method and mechanistic naturalism. We can expect that epigenetics will be held up as the forerunner of that bastard child of Creationism, Intelligent Design. Dribs and drabs of this are already appearing on the Interwebs, but it may soon come to a school board near you. Second, the notion that environmental tags are embedded in our genome within a human time frame has got to be one of the best things to happen to tort law in a long time. DNA typing has led to the conviction of the guilty and the freeing of the innocent. Epigenetic typing may now lead to expert testimony regarding the presymptomatic impact of environmental disasters on susceptible populations. This may seem fanciful, but where there are moneyed interests (on either side), the science will inevitably follow.

By

CNu

at

March 10, 2011

2

comments

![]()

Thursday, March 03, 2011

the rise of "anti-western" christianity

BrusselsJournal | Occidental Christians assume that Christianity is Western. After all, “Europe is the faith”, asserted Hillaire Belloc. Although by birth a Middle Eastern religion, Christianity, at least as Westerners know it, soon became a European religion in the sense that it melded with various forms of European paganism. Christianity, the story runs, cannot exist in a vacuum. It conforms to the various cultures with which it comes in contact. In its European manifestation (after syncretization with Celtic, Germanic, Greek and Roman paganism), Western Christianity became the religious expression we know today. Comfortable with pagan-Christian holidays like Christmas and Easter, most Westerners could not conceive of Christianity any other way. (By “Westerner” is meant a European or someone of the European Diaspora.)

BrusselsJournal | Occidental Christians assume that Christianity is Western. After all, “Europe is the faith”, asserted Hillaire Belloc. Although by birth a Middle Eastern religion, Christianity, at least as Westerners know it, soon became a European religion in the sense that it melded with various forms of European paganism. Christianity, the story runs, cannot exist in a vacuum. It conforms to the various cultures with which it comes in contact. In its European manifestation (after syncretization with Celtic, Germanic, Greek and Roman paganism), Western Christianity became the religious expression we know today. Comfortable with pagan-Christian holidays like Christmas and Easter, most Westerners could not conceive of Christianity any other way. (By “Westerner” is meant a European or someone of the European Diaspora.)Yet Jenkins maintains this is not the entire picture. The idea of “Western Christianity,” he maintains, “distorts the true pattern of the religion’s development over time”. First, even during medieval Europe (which is heralded as the epitome of European Christendom), many Christians lived outside Europe and practiced other forms of Christianity. To the Armenian or Ethiopian Christian, European Christianity would have seemed odd. Furthermore, in more recent times, the missionary work of modern Europe has laid the foundation for a new type of Christianity that is different from anything that preceded it.

If “Europe is the faith” for Western Christianity, then, Jenkins maintains, “Africa is the faith” for the coming Christianity. In 1900, Europe possessed two-thirds of the world’s Christians. By 2025, that number will fall below 20%, with most Christians living in what Jenkins calls the “Global South”, largely a proxy term for “Third World”. The Global South could be thought of as slightly modified Gondwanaland, including Africa, Latin America, Philippines, southeast Asia/India, etc. This Global South, not the West, will be the new heart of Christendom.

The statistics are compelling. By 2025, nearly 75% of the world’s Catholics will be non-Western (mostly African and mestizo). At present, Nigeria has the world’s largest Catholic theological school. Our Lady of Peace in Yamoussoukro may be the world’s largest Catholic church. India has more Christians than most Western nations. By 2050, more than 80% of Catholics in the U.S. will be of non-Western (often mestizo) origins. By 2050, only a small fraction of Anglicans will be English or of the European Diaspora. Nigeria, not England, is the new heart of Anglican Christianity. Lutherans, Presbyterians and other mainstream denominations find their chief centres of growth in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Then there are the ever-growing Pentecostal and other indigenous Christian churches. Pentecostals have made tremendous inroads in Latin America, and churches like the Zion Christian Church have grown tremendously in South Africa. The Zion Christian Church attracts over a million pilgrims every Easter (more than greet the Pope in St. Peter’s Square on Easter mornings).

But this is not simply a matter of static (European) Christianity being implemented by people of other races. Christianity itself is radically changing. The New Christendom is “no mirror image of the Old. It is a truly new and developing entity”. Jenkins writes:

“As Christianity moves South, it is in some ways returning to its roots. To use the intriguing description offered by Ghanaian scholar Kwame Bediako, what we are now witnessing is ‘the renewal of a non-Western religion.’”As once Europeans appropriated Christian iconography as their own, so does the New Christianity in Latin America, where images are filtered through the lens of mestizo identity. The Catholic Church has proclaimed the Virgin of Guadalupe as the patron of all the Americas. Probably the result of syncretization with the Aztec goddess Tonantzin, the Guadalupe Virgin, the dark one (La Morena) as she is called, looks like the local Americanian and mestizo populations, not like Europeans. Likewise, images of the Cuban La Caridad show her “appearing to rescue black and mestizo sailors”. In Equador, the Virgin of El Quinche is popular “because her skin color is that of the local mestizos”. “Ethnically as much as spiritually,” these non-European Virgins are their Virgins.

By

CNu

at

March 03, 2011

5

comments

![]()

Monday, January 31, 2011

Friday, January 21, 2011

post peak medicine - work in progress

PPM | The 21st century will probably be unlike any other century before or since. It will be a century of peaking and then declining natural resources: first oil, then natural gas, water, food, coal and uranium. At the same time, we will have to deal with a record number of human beings on the planet.

PPM | The 21st century will probably be unlike any other century before or since. It will be a century of peaking and then declining natural resources: first oil, then natural gas, water, food, coal and uranium. At the same time, we will have to deal with a record number of human beings on the planet.Our political, economic and media leaders have prepared us poorly for what is likely to come. The overwhelming message from mainstream sources is in effect that we have infinite resources and can enjoy continuous improvement and infinite growth without consequences, and that technology will find a way to overcome any obstacle. When these things fail to happen (which is almost inevitable) there is likely to be much confusion and anger and a lack of consensus about what to do next.

Guidelines for contributors

"Post Peak Medicine" is a book which is being written by and for healthcare professionals. At present it exists as this website, but when completed it will be compiled into a downloadable e-book. The intention behind the book is that it will help practitioners to make the transition to post-peak practices during what may be turbulent times ahead.

I have written Part 1: Framework and Background but I am looking for specialists in their field to write individual chapters in Part 2: Specialties. Your contribution, should you decide to make it, will be valuable both to your professional colleagues and the public. Here are some suggested guidelines for contributors which I hope you will find helpful.

You must have a recognised qualification within your healthcare specialty.

When the book is completed and published, all contributions must be attributable to a named author(s).

Each chapter need only be a few pages long, and should be about the challenges you foresee in adapting to post peak practice and how those challenges might be overcome. Don't try to write a detailed textbook about your specialty, but where detail is needed, please provide links or references to sources of information you consider helpful. If you find it difficult to imagine what your specialty will be like post-peak, it may be helpful to put it in a historical context: for example, what methods did your specialty use fifty or a hundred years ago?

Pictures and illustrations are welcome, but please ensure that you hold the copyright, or that you have obtained permission to use them, or that they are copyright-free.

This book will not be released to the public until all contributors agree that it is time for it to be released. This may be either when it is completed, or when the public attitude towards peak oil and related issues has changed to the extent that it is possible for serious discussion about them to take place in mainstream circles.

This book can't solve all of these problems, but maybe it can help in a small way. It is intended mainly as a guide by and for healthcare professionals, to help ease our transition into a post-peak healthcare system. Thank you for your interest in contributing to this book. For further information please contact info@postpeakmedicine.com

By

CNu

at

January 21, 2011

1 comments

![]()

H.R. 6408 Terminating The Tax Exempt Status Of Organizations We Don't Like

nakedcapitalism | This measures is so far under the radar that so far, only Friedman and Matthew Petti at Reason seem to have noticed it...

-

theatlantic | The Ku Klux Klan, Ronald Reagan, and, for most of its history, the NRA all worked to control guns. The Founding Fathers...

-

Video - John Marco Allegro in an interview with Van Kooten & De Bie. TSMATC | Describing the growth of the mushroom ( boletos), P...

-

Farmer Scrub | We've just completed one full year of weighing and recording everything we harvest from the yard. I've uploaded a s...